Proteus Emerges in the Early Church (Part III)

An Historiographical and Stylistic Examination of Three Pauline Speeches in Acts | Speech Recording in Antiquity & an Analysis of 3 Pauline Speeches

This is a continuation of a piece on Luke-Acts and Historiography. If you have not read the first entry or the second, then you might be a bit lost picking up here at the end of the study.

As a note on this particular analysis: The main argument is contained within the body of the article. For finer details and further explanation, dig into the footnotes. This exploration would have been twice as long had all the notes found their way into the main examination.

Friends, Romans, Countrymen, Lend Me Your Ears: Speech Recording in Antiquity

The presentation of speeches in antiquity can be a contentious discussion because there are disparate views concerning how reliable these accounts actually are.1 As Jeffery Henderson stated with respect to Polybius,2

As was the custom of Greek historians, Polybius included speeches in his narrative. The question for him, as for other historians, is whether or to what degree the speeches resembled what was actually said in a given situation, or whether they were, in substance, inventions of the author himself attempting to capture the speakers’ intentions.3

The points presented above must be taken into serious consideration, since there is great likelihood that there was a blending of truth and fabrication in speech-craft. Mark Harding notes,

Historians did not think that it was either edifying or entertaining to report verbatim what was said on such occasions even if such reports were available. Rather they sought to provide the sense of what had been said, rendering the speech in accordance with rhetorical conventions. In this way historians were able to make their speeches more effective as vehicles of persuasion for their discerning audience.4

As was stated previously, history is written for a purpose; the genre did not exist then nor does it now just to present dead material. Because of this, the historical figure became a mouthpiece for the historian, similar to other genres that were examined. If you believe Plato, for instance, is merely presenting what Socrates said and believed, you are gravely mistaken. So, the Gospels and Acts are very much in this same tradition of presenting historical settings—some narratives are certainly invented—in order to make theological assertions.

This paper has not the space to wrestle with every view concerning speeches from antiquity, for, as J. S. Rusten asserted, “The literature is endless.”5 Be that as it may, we must attempt to tackle the topic to the best of our ability. In all honesty, it is impossible for us to determine without a shadow of a doubt the genuineness of the speeches in Acts, but there are two points that we must consider. What J. S. Rusten astutely contended about the speeches in Thucydides can also apply to Luke-Acts:

The vindication of either view would bring important advantages for our study of Thucydides: if they are faithful, we gain valuable reports of the policies and perhaps even the personalities of the most important Athenian and Spartan leaders. If they are entirely fictitious,6 then we may isolate them as “editorial comment,” revealing Thucydides’ own opinions to a greater extent than he could in his narrative sections.7

Truly, though, we can eat our cake and have it, too, at least to some extent. The speeches that Luke records, as we discussed with respect to modern historical theory, are chosen for a purpose. Thus, if they are based on historical reality, the fact that Luke included them in his narrative says something about the account and what he thinks about the situation. This is a delicate situation since it is nebulous as to which sections are true reports and which are commentary.

An Examination of Three Pauline Speeches

Regardless of such uncertainty, let us explore three speeches in particular to illustrate Luke’s desire for a “Thucydidean” presentation of Paul.8 The three pericopes that we shall explicate are found in 13:13–52 (Paul and Barnabas in Antioch), 17:16–34 (Paul on the Areopagus in Athens) and 20:17–38 (Paul speaks before the Ephesian elders).9

The discussion will revolve around historical plausibility and the Proteus model presented at the beginning of this analysis. Clarence E. Glad’s discussion, “Paul and Adaptability,” shall serve as a lens through which we can explore these speeches. When considering this thesis in combination with the Proteus language, a Paul emerges that is able to adapt to any situation where the Gospel is pronounced.

We should examine Paul’s rhetorical and literary strategies employed in his letters for the general requirement of letter writers to take into account the circumstances of their addresses.10

And so, Luke exploits this detail from the Pauline corpus, for he most likely was familiar with 1 Corinthians or, at least, the sentiments expressed therein.11

The following three segments will contain the same basic outline for assessing the speeches of Acts. The audience, structure,12 and citations are key aspects for each speech. The historical surroundings and details of the account may also contribute, and they will be assessed as necessary. We shall not explore at length the outcome nor the meaning of each speech because that is not the intent of this study. Now, let us progress to Paul’s address to the Jews in Antioch of Pisidia.

“After the Reading of the Law and the Prophets”: Paul Before Jews

Paul’s speech before the Antiochian Jews is a unique presentation that focuses on the historical importance of Israel for the incipient Church.13 Examine the charts concerning the narrative and the structure of the speech:

The Structure of Paul’s Speech to the Antiochian Jews

(v. 16b) Introductory Statement

(v. 17–25) The History of Israel Leading up to John the Baptist

The History of Israel in Egypt and the Land of Canaan [17–20]

The Cycle of Judges [20]

The Establishment of the Monarchy, David, and the Messiah [21–23]

John the Baptist [24–25]

(v. 26–32) Jesus, his Passion, and Paul's Proclamation of the Gospel

(v. 33–35) The Fulfillment of Scripture

(v. 36–41) The Conclusion: David, Salvation, Moses, and a Warning

Audience

Let us begin with the audience present at this speech.14 The introduction just prior to the speech (vv. 13–16a)15 makes no mention of those in the congregation apart form οἱ ἀρχισυνάγωγοι (“the officials of the synagogue”) who sent a message for Paul and his companions. Paul’s introductory statement clarifies little, for the text simply reads,

ἄνδρες Ἰσραηλῖται καὶοἱ φοβούµενοι τὸν θεόν

Men, Israelites and those who fear God (or, God-fearers).16

There are a number of potential meanings in the phrase “God-Fearer”:17

A group of Israeli men (and presumably women) and Gentile converts

A group of Israelites where the second phrase is just pleonastic—this is unlikely18

The other mentions of the audience arise in v. 26 (Ἄνδρες ἀδελφοί, υἱοὶ γένους Ἀβραὰµ καὶοἱ ἐν ὑµῖν φοβούµενοι τὸν θεόν) and v. 43 (πολοὶ τῶν Ἰουδαίων καὶ τῶν σεβοµένων προσηλύτων). V. 26 offers little extra to the address. Potentially, though, it offers more of a designation for the second group since the text reads, “and those who fear God among you,” but it is nothing definitive. V. 43 provides additional clarity, potentially. Based upon this verse, we can infer that Paul spoke to two possible groups: (notable) Jews and Gentile converts.19 As Luke Timothy Johnson states,

The designation of Cornelius as one “fearing God”... inevitably raises the difficult issue concerning “God-fearers” and their relationship to first-century Judaism. Luke’s use of the expressions “those who fear God” (hoi phoboumenoi ton theon; 10:1, 22, 35; 13:26) and “those who reverence God” (hoi sebomenoi [ton theon]; 13:43, 50; 16:14; 17:4, 17; 18:7), together with scattered references elsewhere (e.g., epigraphy, Josephus, Against Apion 2:39; 2:282–286; Antiquities of the Jews 14:116–117; Juvenal, Satires 14:96–108), have led to a variety of scholarly positions concerning the existence or status of a group of Gentiles who were not formally proselytes (full converts, with circumcision and the observance of the laws), but who nevertheless frequented the synagogue and tried to live as much as they could by the code of Torah.20

Thus, based upon these two further descriptions, it appears that Luke has provided little information to indicate that there are any in the audience who would not be familiar with Israelite history. V. 46 makes certain of Luke’s intended audience when Paul pronounced, “It was necessary that the word of God should be spoken first to you. Since you reject it and judge yourselves to be unworthy of eternal life, we are now turning to the Gentiles...” In Luke’s mind, the audience of Paul’s “homily” consists of Jews and Jewish sympathizers.

Structure

The structure of the speech is fairly clear.21 According to Mikeal Parsons, the technical rhetorical structure of the speech can be described as follows,

The speech itself reflects a structure easily recognized by an audience familiar with conventions of ancient rhetoric: 13:16b, a brief exordium or introduction establishing audience favor; 13:17–25, a review of Israelite history in the form of a narratio or narration, a statement of the “facts” of the case; 13:26, the probatio in which the speaker states a proposition... and finally, 13:38–41, the peroratio or epilogue, in which the hearers are urged to accept this salvation.22

As the structured outline above illustrates, Paul briefly traces the history of the Israelites, from the breaking of their chains in Egypt until the establishment of the monarchy. His argument is tailored for an audience composed predominantly of Jews since Gentiles would not be aware of their wayward history.

The structure has resonances to numerous passages in Scripture.23 Pervo claims, “Although the speech is steeped in scriptural allusion and citations, it is Christian in character. The survey of salvation history ignores both covenant and Torah.”24 This is an astute point, for the message expresses nothing explicitly about Law/Covenant in the recounting of tradition; the discussion simply transitions to a summary of Christ’s passion story as a continuation of the Jewish narrative.

V. 29 even depicts Paul asserting that “When they had carried out everything that was written about him, they took him down from the tree and laid him in a tomb.” According to the Lucan Paul, Jesus fulfills the history that has been disclosed in the Hebrew Scriptures.25 Upon completing this interpretive history, Paul then supports his claims by exegeting numerous passages from the Old Testament. Paul caps off his monologue addressing the resurrection of Christ and one final scriptural passage warning the Jews of condemnation if they do not believe Paul’s words.26

Citations

As for citations found within the speech, Paul quotes five directly before his audience. Vv. 33–35 contain three (Ps 2:7; Is 53:3; Ps 16:10) in order to illustrate Christ’s fulfillment of Scripture. This argument desires to rebut the dissension amongst the Jews to Christ’s message, as is expressed in v. 27 explicitly. Paul repeatedly appeals to the tradition and ancestry of the people to reveal the continuity of Christ and his own mission (vv. 26, 36, 38).

The fourth piece of Scripture quoted before the audience (v. 41; Hab 1:5) is used as condemnation if the listeners reject his message. The tension, of course, escalates in the narrative, but many convert. The final quotation in v. 47 (Is 49:6) serves as a personal identification and justification of Paul as one sent to the Gentiles. This becomes a transitional point for Paul's mission because he then turns his journey to those outside of his heritage.27

“Even as Some of Your Poets Have Said”: Paul’s Gospel and Athens

After preaching in Antioch, Paul’s journey continues until he reaches the land of Greece wherein he stays for a time at Athena's city. The emphases of this speech differ greatly from what we just examined in Antioch. Let us now explore the speech Luke has provided.

The Structure of Paul’s Speech on the Areopagus

(v. 22) Introductory Statement

(v. 23) The City of Athens and the Inscription “To an unknown God”

(v. 24–27) The God of Israel and the Unknown God28

(v. 28) As the Epicurean Says

(v. 29–31) The Argument: God’s Offspring, Idols, Judgment, and Resurrection

Audience

The audience of this particular speech does not necessarily pose fewer dilemmas than our previous address. Disgruntled on account of the idols present in the city, Paul seeks to debate—not too differently from Socrates. Paul seeks out his own brethren first and heads to the synagogue where he begins to dialogue with the Jews (τοῖς Ἰουδαίοις καὶ τοῖς σεβοµένοι). Luke informs us that these debates did not quench his thirst for conflict, so he, in good Socratic fashion, ventures off to the agora wherein he could verbally spar with “those who happen to be nearby” (τοὺς παρατυγχάνοντας).

Luke thought it fit to go even further and divulge that there were also Epicureans and Stoics who sought to refute this neo-socratic curmudgeon who was stirring up trouble.29 The final assessment concerning the audience entails v. 22 (the speech proper) and v. 33 (the closing of the pericope). V. 22 simply gives us little extra information other than that he addresses the audience quite similarly to the Jews in chapter thirteen, Ἄνδρες Ἀθηναῖοι. In the closing verse of the event, two names are mentioned, Dionysius, the Areopagite, and Damaris, which are two Greco-Roman names. Thus, it is a fair assumption based on these details that Luke has framed this speech before a Gentile audience.

Structure

The structure of this address is not all too different in form than the one previously explored. Dean Zweck offers a rhetorical analysis similar to that of chapter thirteen; here, vv. 22–23a is the exordium, v. 23b is the propositio, vv. 24–29 is the probatio, and vv. 30–31 is the peroratio.30 After the introductory phrase, Paul leaps right into Jewish-like tradition, albeit masked with a philosophical foundation since he now speaks before a group of Greeks.31 Be that as it may, Paul addresses their inscription “To an unknown God,” and then posits that he knows who this god is.

He delves into a Genesis-like account of God as creator and then segues into common ancestry, a brilliant rhetorical ploy in order to include the Gentiles32 because he then speaks of their own poets to draw them in.33 The first quotation relates back to what was said about the unknown god, and the second serves transitionally. An idol bashing polemic then commences in v. 29ff. along with a discussion of future judgment that is quite reminiscent of Paul’s Epistle to the Romans.

There is contention surrounding this section of Acts since it is difficult to determine the Greco-Roman and OT influences that may have impacted Luke. There are many elements in this speech that resonate with Greco-Roman themes such as Athens itself (Areopagus), the inscription “To the unknown God,”34 and the quotation by Aratus (v. 28). In spite of that, there are some Jewish parallels in this text, since that is ultimately the foundation of Paul’s beliefs (the Creator God and the Idol Polemic).35

These Greco-Roman and Jewish elements reveal the convoluted nature of Paul’s speech. Luke astutely represented the missionary to the Gentiles, that Paul was able to adapt his Gospel for a predominately Greek audience. At the close of the address, Paul makes a quick mention of the resurrection, and then the monologue collapses and the speech abruptly stops.

Citations

The citations present in this speech come not from the Old Testament, but instead from a Greek poet, Aratus’s Phaenomena (5).36 Luke has Paul quote a verse from Aratus similarly to how he would have Paul cite Scripture. According to Pervo,

The speech suggests that Greek writers provide opportunities for insight into the God proclaimed by Jesus and the message about Jesus in a manner comparable to the Israelite sacred writings.37

He further claims that the logic only lends itself to Gentile converts. Regardless, the quotation serves as a segue into v. 29, which is rather similar to how Paul uses Scripture in Acts.38 Paul’s logic is, since we are the offspring of God, then he must not be an idol; notice the near direct quotation:

τοῦ γάρ καὶ γένος εἰμέν—Aratus, Phaenomena 5

τοῦ γὰρ καὶ γένος ἐσμέν—Acts 17:28b

“For we, also, are his offspring.”

It is impossible to state decisively if this speech occurred even remotely similar to what Luke has presented us, if it happened at all. The most we can say is that the presentation of the Gospel in this pericope is stylistically different from Paul’s address to a predominantly Jewish congregation, yet still fits the formulaic structure.

Schröter comments on Acts 17 that

The Areopagus speech thus shows itself to be a production of the historian Luke, who links the activity of Paul with his historical consequences... The Areopagus speech represents a sketch of a Pauline missionary sermon to Gentiles, which Luke intentionally moves to Athens.39

Be that as it may, there is some form of truth lingering beneath the text with which Luke is working.

“I Testified to both Jews and Greek...”: Paul and the Ephesian Elders

The third speech of our study is entirely different in form and function compared to those previously discussed. This speech was not intended for an audience of non-“Christians,” but instead to an established church in Ephesus. This address is an exhortation (paraenetic) while also serving as Paul's farewell discourse in the narrative history.40

The Structure of Paul's Speech in Ephesus

(v. 18b–21) Introductory Statement41

(v. 22–24) Paul Reveals his Plans (Missionary Journey)

(v. 25–31) Moral Exhortation and Warning

(v. 32–35) An Apology42 & Conclusion

Audience

The recipients of this speech are plainly obvious from the text; this is not a proclamation of the Gospel as the other two have been. As indicated above, Paul is speaking before a group of elders in an established Christian church.43

Structure

The structure of this monologue is quite different from the past two.44 When Paul spoke in Antioch and Athens, he was proselytizing to two exceedingly different groups, but the messages for both were quite similar (in both form and content). Now, since his reason for speaking has changed, his structure and thesis have shifted to what is required of him.

Rhetorically, the speech begins with an appeal to Paul’s credentials;45 it is an establishment of pathos (18b–21) through a reminder of all that Paul has done (ethos).46 Paul details his previous journey to this church and reminds them of all he has done, mainly proclaiming the Gospel to them, the Jews, and the Greeks. This speech in particular is excellent to conclude our study, since it serves as a book end.

In chapter thirteen’s speech, there is a message given to the Jews, but they reject the message. Thus, Paul shakes the dust from his boots and proceeds to preach amongst the Greeks, and there was much rejoicing. Here, Paul exclaims, “I testified to both Jews and Greeks.” This is the final speech that Paul will give on his journeys because he is headed to Jerusalem (as did Christ)47 and then to Rome (where he will die, presumably).48

At v. 22, we have a disruption in style, which indicates a shift in the monologue. There is a parallel structure in vv. 22 and 25 (καὶ νῦν ἰδοὺ), and a variant in v. 32 (Καὶ τὰ νῦν)—all three indicate a new segment of the argument.49 Based upon these verbal cues, I have chosen to interpret the structure of the speech as follows.

In this second block, Paul discusses his missionary plans for proclaiming the Gospel. He asserts that he is on his way to Jerusalem, which is reminiscent of Jesus’s own journey towards death.50 A significant shift then occurs in v. 25 where Paul begins to expound on how they will not see him again, and he then exhorts them as a community. V. 33 ff. closes the monologue, which serves as a further apology since Paul defends himself before them.51 It is unclear if anyone has charged him with abusing his time amongst them, but it seems unlikely because of the short nature of the discussion. At any rate, Paul closes his speech with a quotation from Jesus.

Citations

Lastly, there are no direct quotations in this passage. Luke was not lacking in Scripture when Paul spoke before the Antiochans, and he supplied a reference for the Gentiles with a quotation from one of their poets. Here, fittingly, Paul appeals to the words of Christ in v. 35, “It is more blessed to give than to receive.”

This is not a known phrase amongst the logoi of Christ known from the Gospels. This is potentially Jesus tradition in Acts. The quotation is akin to Sir 4:31, which reads, “Do not let your hand be stretched out to receive and closed when it is time to give.”52 As for the Jesus tradition found in this pericope, Pervo offers a constructive analysis,

The verse opens with a reinforcement of Paul’s role as an example. The final speech of Peter’s missionary career climaxed with an appeal to the words of Jesus (11:16). Within the Pauline tradition 1 Thess 5:15–17 is a good parallel. Both utilize a saying (λόγος) as the warrant for exhortation. Paul introduces the aphorism with a formula used for citing oral tradition that first appears in Christian literature in 1 Clement (13:1–2; 46:7) and thereafter in the fragments of Papias and in Polycarp. The formula used in 11:16, which is quite similar, ostensibly reproduces Peter’s recollection of what Jesus said, and 1:5 shows but a slight variation from it. This aphorism, however, does not appear in either Luke or Acts. The “agraphon” indicates that for Luke the door for sayings of Jesus remained open and was not limited to his written Gospel.53

This is particularly intriguing, since we have found red thread in these three speeches: an appeal to a source outside of Paul’s mind that serves as foundational evidence for his claims. This is a consistent theme for Luke in the Pauline speeches we have examined.

Stylistically, the speech before the Ephesians appears to be more Pauline in the sense that it parallels more of what Paul would say in his extant epistles. There, also, resides Jesus tradition that is not extant in the canonical Gospels, which leaves much to ponder.54

Synthesis & Conclusion

Our study has attempted to explore an expansive subject in quite a short amount of space. Obviously, much more could be said in each section because the topics addressed are so convoluted and intertwined. Since I was unable to cover a broad range of ancient literature thoroughly, this examination is greatly stunted. I have unearthed connections and I have hypothesized others that have not been covered, but I hope to pursue them in later research.55 In this final section, though, let us try to synthesize what we have explored and see if there is a sensible conclusion we can make.

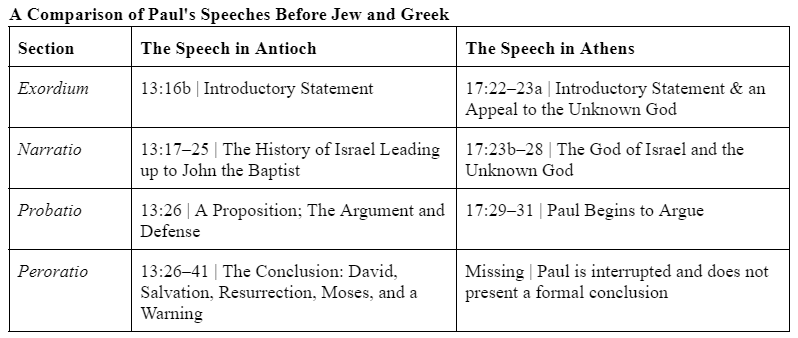

The initial two speeches we explored are strikingly similar in form and content, but the emphases are what vary. Both of them contain the general structure of Introduction, narratio & probatio, outside wisdom (through a citation of Scripture or Greek poet), and resurrection. The two have nuances and divergences, but the structure is generally the same.

One speech is for a Jewish audience while the other for Gentiles. Even if Pervo is correct when he asserts that only the audience of Luke’s work will comprehend the message, that does not signify that there is no historical basis for what was said. After all, history must be written and interpreted for the present audience lest its importance be lost to time. Thus, Luke is required to make clear what occurred for the current audience. Regardless, let us now compare the structure of both speeches.

Aside from the structure, there are other elements that exist in both. Paul focuses on God differently in the two, but that is the foundational element for both speeches. Quotations occur in both; in the first, Paul quotes the Old Testament extensively, but in the second, he appeals to a poet from Greco-Roman culture. Thirdly, there is an emphasis on the resurrection, which seems to be problematic in both accounts. The final common element to mention is Christ. Paul mentions Jesus by name in Antioch, but he only states before the Athenians, “a man whom he has appointed, and of this he has given assurance to all by raising him from the dead.” Obviously, Paul is referencing Jesus in this pericope.56

From this cursory exploration provided above, we can conclude that the two speeches are, at the very least, based on the same basic structure. Paul is interrupted in Athens, which disrupts the order of the speech, but the overall form is the same. The key arguments are to gain converts to the Church, but their modes of operation differ.

Luke portrays Paul as the Proteus of the Early Church. Depending on the circumstances, Paul would adapt his presentation for the audience. His message, though, was consistent, which can be seen in Luke’s account: both the Jews and the Greeks found Jesus and the resurrection problematic. Luke shows Paul in a more positive light amongst Gentiles, though, since the memory of Paul was in association with the Greco-Roman world.

Finally, the main goal of writing history is ultimately to state a grander point rather than just prattling off factual occurrences; this is accomplished when the author elects to join together various pericopes into his narrative imbuing them with meaning—interpretation. If one examines the Gospel stories, the theology and Christology carry more significance than the veracity of certain particularities; so it is with Luke’s Doppelwerk.

To be sure,

A good historian will interact dialogically with historical record, recognizing the limits it places on possible construals of the past. Of course historians select their facts, and obviously the stories they tell are incomplete. But by itself this does not mean that the result is distorted or false.57

Such is the case with Luke’s account, for his narrative was constructed in order to compose a Christian myth that would unify a diverse community. Embellishment, in turn, is a factor in the writing of history; it is common to highlight aspects of importance in order to illustrate a greater theme of the written work. Tolkien aptly conveyed this point through the words of Gandalf:

Old Took’s great-grand-uncle Bullroarer...was so huge (for a hobbit) that he could ride a horse. He charged the ranks of the goblins of Mount Gram in the Battle of The Green Fields, and knocked their king Golfimbul’s head clean off with a wooden club. It sailed a hundred yards through the air and went down a rabbit hole, and in this way the battle was won and the game of Golf invented at the same moment.58

The veracity of Luke’s two-part narrative of the incipient Church cannot, therefore, be seen solely through a modern perspective. It is imperative that one first acquires a sense of Luke’s evaluation of history and how he has decided to formulate the historical narrative of his Church. I proposed that Luke, as a historian, was a border-crosser, and Paul, as a narrative protagonist, was Proteus.

Luke had a knack for blending and fusing together the traditions he inherited. By cleverly combining his understanding of Jewish sentiments of God’s involvement in history with the narrative style of Hellenistic speech formulation, Luke has effectively shown that he can appeal to both Jew and Greek alike. The instrument he employed was his Christian Proteus, Paul the Apostle, his star character who was able to adapt and change his speeches in order to appeal to a diverse array of audiences. Thus, the authenticity of every modicum of detail in Luke’s Gospel and history are of smaller significance when gazing at the grand portrait that Luke has artfully crafted.59

His depiction of Paul and the Early Church serves a greater purpose than just recording straight facts, for it would be dead material without the interpretive flavor that Luke so ingeniously added to the mix. After all, “Wine mixed with water is sweet and delicious and enhances one’s enjoyment. So also the style of the story delights the ears of those who read the summary account” (2 Macc 15:39).

If you wish to keep reading about the New Testament and the Early Church, would you kindly subscribe?

With that said, a full discussion of the various views will not be recorded in this paper. The debate will lie under the surface of this analysis as it will become apparent how each commentator views the speeches that we examine. A brief discussion will be had in this introductory material, and the nuances of this debate will be shown in part from the following examinations. For general discussions on the speeches in Acts, see M. Soards, The Speeches in Acts (Westminster, 1994); G. Horsley, “Speeches and Dialogue in Acts,” NTS 32 (1986): 609–614; H. Cadbury, “The Speeches in Acts,” in The Beginnings of Christianity, part 1, The Acts of the Apostles (Macmillan, 1933).

I choose to begin here with Polybius because the field quickly rushes to Herodotus and Thucydides since it is believed that only a “few, notably Herodotus and Thucydides distinguished between eye-witnesses who could be carefully cross-questions and all later testimony that was beyond such personal control…” (Finley, Ancient History, 8). See Hdt. 3.122 and Thuc. 1.20–21.

Jeffery Henderson. Polybius LCL (Harvard, 2010), xviii. See 36.1.7 and 12.25b.1.

Mark Harding, Early Christian Life and Thought in Social Context (T&T Clark, 2003), 109.

J. S. Rusten, The Peloponnesian War (Cambridge, 1988), 7. The corpus of literature that wrestles with the speeches in Luke is also as interminable as Strepsiades’ night (Artistophanes’s Clouds).

As R. G. Collingwood, The Idea of History (Oxford, 1946), 30, 31 argued, “The speeches seem… to be not history but Thucydidean comments upon the acts of the speakers, Thucydidean reconstructions of their motives and intentions.”

Rusten, The Peloponnesian War, 8.

As I stated in a previous note, I do not mean to imply that Luke is working with Thucydides specifically in mind. Rather, I believe that there is some historiographical ideal lingering in the milieu when Luke composed his Gospel and Acts. There is some debate as to how reliable Thucydides’s complicated statement is, but I believe based on all that we have seen previously, that historical accuracy was a point of concern to some extent at this time. For a balanced examination, see Porter, “Thucydides 1.22.1 and Speeches in Acts.”

I had hoped to explore Paul’s apology before Felix (chapter 24), but time did not permit a thorough examination of this text. Be that as it may, I planned to explore how Paul defended himself in comparison with Socrates’s own defense in Plato and Xenophon’s Apology. Perhaps this could be added on to the series at a later time.

C. Glad, “Paul and Adaptability” in Paul in the Greco-Roman World (Trinity, 2004), 25.

Concerning 1 Corinthians 9, also consult Margaret M. Mitchell, “Pauline Accommodation and ‘Condescension’ (συνκατάβασις): 1 Cor. 9:19–23 and the History of Influence” in Paul beyond the Judaism/Hellenism Divide (Westminster, 2001). In a similar vein, Beverly Gaventa, Acts (Abingdon, 2003), 254 comments on Acts 17, “What Paul’s sermon does, then, is to take basic presuppositions of the Christian gospel and translate them into language available to the narrative audience.”

Although I am not in total agreement, I think this is a helpful starting point. There is more to Luke’s presentation of Paul than just a rough caricature for the narrative audience. As discussed concerning Tweed’s religious theory, Luke’s narrative history is a myth that became fact (see also Tolkien and Horrell); it is rooted in genuine nuggets of history and then interpreted for a community that is seeking solidarity amongst difference.

Although intriguing, the ramifications of disrupted speeches will not be explored in this paper. Their importance and literary function may be significant, but ultimately tangential for our study. For more, see J. Garroway, “‘Apostolic Irresistibility’ and the Interrupted Speeches in Acts,” CBQ 74 (2012): 738–752.

In a paper of this length, a full analysis of all the speeches in Acts from all the actors is impractical. R. Pervo, Acts (Fortress, 2009) claims that the speeches of Paul and Stephen are exceedingly similar to the speech presented here in chapter thirteen. We cannot hope to evaluate the stylistic differences between other speakers in Acts, so this will have to be left untouched. We can only hope to analyze Luke’s presentation of Paul’s rhetoric for this paper. Briefly, Pervo (337) wrote, “Luke wishes to show the commonality of the ‘gospel’ of Peter and Paul.” This is not entirely false; this could also be why the Peter-Paul conflict is absent from the narrative. Luke sought a community united under Christ, and he achieved this end through a narrative history portraying the leaders being of one mind. For others who see the continuity between figures in Acts, see Luke Timothy Johnson, The Acts of the Apostles (Liturgical, 1994). H. J Cadbury, “The Speeches in Acts,” Beginnings I.5, 402–427 holds that the speeches are Lucan compositions due to this detail.

Pervo (Acts, 334) strongly asserts,

The speech (vv. 16–41) fully exposes the unhistorical character of the missionary speeches in Acts. Although it purports to be a speech of Paul in a Diaspora synagogue, even a superficial reading indicates that the sermon is directed to the readers of the book rather than to the dramatic audience, which would have found much of it confusing and/or unintelligible.

This statement seems too harsh with respect to Acts. It is obvious that Luke is writing a narrative for a specific community, so everything included in the work is intended for this specific audience. Although this certainly is not verbatim what Paul said, in all likelihood, there is no reason to outright reject the possibility that he would say something of this nature. Just because it seems unintelligible to us, Luke is most likely condensing the speech to resemble a similar speech that Paul may have said. The jumps in logic are presupposed at the community level, so Luke consolidates what was said. That does not mean that the historical grounding of the speech should be thrown out entirely.

Since it is of no direct influence on the speeches here, I have decided to relegate this comment to the notes. Notice that vv. 13–14a contain a travel log of where Paul had been traveling prior to coming to Antioch and the synagogue. This contains the characteristics of geography and history as discussed in the second article.

The phrase, “God-fearers,” has initiated much debate in Lucan scholarship. For a fuller discussion than I can offer here, consult Pervo, Acts, 332–334.

“The label ‘God-Fearer’ could be applied to any whom Jews viewed as supportive, whether for political, humanitarian, religious, or other motives. According to Josephus Ant. 20.195, Poppaea Sabina, the wife of Nero, was a θεοσεβής” (Pervo, Acts, 333).

I have found no grammatical or lexical support for this, nor do the commentaries mention this as a possibility. Most likely, Luke intended to reveal two separate groups in the audience, but they are both religiously Jewish.

Note Pervo (Acts, 341–342) casts uncertainty on this language,

Verse 43 contains a puzzling expression: σεβόµενοι προσήλθτοι, rendered (with considerable hesitation) “observant converts.” The adjective “devout” otherwise refers to gentile “God-Fearers” (13:50; 16:14; 17:4 [with the noun “Greeks”]; 17:17; 18:7). Elsewhere in Acts, the noun refers to gentile converts to Judaism (2:11; 6:5). It is unlikely that the text wished to contrast dutiful converts with the less observant.

Pervo then expounds on possible resolutions for why this construction is here in this form. Parsons (Acts, 192) and Haenchen (Acts, 346) show that οἱ φοβούµενοι τὸν θεόν commonly signifies Gentiles who are accustomed with, or sympathetic towards, Judaism.

Johnson, The Acts of the Apostles, 182.

It is difficult to surmise, though, the model that Luke had in mind. Pervo rejects John W. Bowker's (“Speeches in Acts: A Study in Proem and Yelammedenu Form,” NTS 14 [1967–68]: 96–104) thesis that links this speech with a synagogue homily. Pervo (Acts, 334) states that the Scripture readings are necessary to properly assess the parallel.

M. Parsons, Acts (Baker, 2009), 191–192. Parsons hold that the divisions for rhetoric are not set; “the analysis above follows the divisions of Quintilian (Inst. 3.8.1–5), who, contra Cicero (Inv. 1.14.19), does not consider the partitio (the central claim of the narratio) as a separate section” (192). For a fuller explanation of the rhetorical structure of this speech, see chapter six in C. Clifton Black, The Rhetoric of the Gospel (Chalice, 2001).

The Nestle-Aland 28 provides in the margins of the text a myriad of parallels in order to reveal that Luke is working with an expansive amount of Jewish tradition.

Pervo, Acts, 335. I would like to push back slightly on this claim since the Law of Moses is mentioned in v. 39. Although it is not Torah nor covenant, it is reminiscent of Paul’s discussion of the Law in Romans.

See also Johnson, The Acts of the Apostles, 234.

Ironically, the Antiochian Jews reject Paul's Gospel, and he then begins to minister to the Gentiles.

Luke makes this explicit in v. 48 when the Gentiles rejoice that the word of God is coming to them. Again, this is Luke attempting to establish solidarity in the community, for God chose to include the Gentiles to be among his people. Luke makes certain the reader does not miss this point because the Jews then kick them out of the city and the two missionaries “dust off their feet in protest” as commanded by Jesus in Luke 9:3–5. Luke Timothy Johnson (The Acts of the Apostles, 237) intriguingly notes, “Luke obviously intends by this sort of narrative mimesis to establish the continuity between the prophetic ministry of Jesus and the one who, we now learn, is the one who is to be ‘light to the Gentiles’ (13:47; see Luke 2:32).” Johnson astutely parallels Jesus’s hometown experience with Paul’s mission to his own people. The comparison is insightful for understanding the Lucan Paul—potentially “be imitators of me, as I am of Christ” (1 Cor 11:1).

Arguably this is akin to the history of Israel from the speech in Antioch. It relates back but in more simplified terms. They would not have been able to understand a full recounting of Israelite history.

I am whimsically using Socrates as a parallel because it is an interesting feature that may be lurking under the prologue. Pervo (Acts, 424) notes the possible allusion to Socrates’s method concerning διαλέγοµαι: Plato, Apol. 19D; 33A; Resp. 454A. If this exists in the text, it adds further to the Greco-Roman connections to the history. It is interesting that v. 18 states, “Some said, ‘What is this babbler want to say?’ Others said, ‘He seems to be a proclaimer of foreign divinities.’ (This was because he was telling the good news about Jesus and the resurrection).” Socrates was put to death for disrupting the status quo; he challenged the populace’s beliefs concerning the gods as well as corrupting the youth.

See Haenchen (Acts, 518) who claims, “Xen. Mem. I.1.1: χαινὰ δαιµόνια εἰσφέρων—hence Luke chooses the word δαίµονες here.” Luke’s portrayal of Paul is not all that different since he disrupts the community to such a degree that they rush him up to the Areopagus. Other scholars have made note of this potential parallel; see Karl O. Sandnes, “Paul and Socrates: The Aim of Paul's Areopagus Speech,” JSNT 50 (1993): 13–26; David M. Reis, “The Areopagus as Echo Chamber: Mimesis and Intertextuality in Acts,” JHC 9 (2002): 259–277. Pervo notes a number of works that make reference to Socrates parallels in Acts; see Hans Dieter Betz, Der Apostel Paulus un die sokratische Tradition (Mohr, 1972); Abraham Malherbe, Paul and the Popular Philosophers (Fortress, 1989).

Dean Zweck, “The Exordium of the Areopagus Speech, Acts 17.22, 23,” NTS 35 (1989): 94–103.

See Pervo (Acts, 430) who claims, “The intellectual background of this sermon derives, in general, from that Stoic line of thought associated with Posidonius, who reasserted the early Stoic view of a divine providence revealed in nature and history.”

“Genesis-like” is fitting to draw out the Jewishness of this Greco-Roman argument. Johnson, The Acts of the Apostles, 316 states, “As in midrashic arguments, Paul immediately picks up the key word, genos (‘family/offspring’) for his conclusion. It is probable that Luke understood this kinship along the lines of being created in God’s image (Gen 1:26), for that is the direction the argument takes.”

Pervo (Acts, 429–430) claims,

A cultured Greek would dismiss these brief words as a stylistically inadequate and muddled collection of clichés with an unexpected and improbable conclusion, but it has power and vigor that would have eluded such critics, and, as an experiment in missionary theology, it continues to challenge Christian thinkers.

Although I see Pervo’s point, I fail to perceive the exact reason for why Luke would confront his community in such a manner. Luke is communicating a message to his intended audience, but he does so through a narrative history that catalogs an early champion of the faith. Yes, this is an abbreviated argument that would not hold water before an erudite Greek philosopher, but it resonates with Paul’s adaptability. Luke may have chosen too much to accomplish in his Doppelwerk, but I do not believe that discredits the historicity of the speech, rendering it as pure teaching for his community. Why would Luke go to such ends to represent rhetorical shifts if the message was the only part of importance?

The inscription “to the unknown god” is problematic due to the lack of archaeological evidence to support its existence. F. F. Bruce (The Book of Acts, 335) reveals that despite the lack of physical evidence, authors such as Pausanias (Descr. 1.1.4), Philostratus (Vit. Apoll. 6.3.5), and some Early Church writings (Cf. Didymus, Fr. 2 Cor., 10:15) bear witness to its existence, at least in literature. Although there is no evidence that reveals this inscription’s presence in Athens, there is archaeological attestation of “altars on the road from Phaleron to Athens, in Olympia, and perhaps also in Pergamum, which were dedicated to ‘unknown gods.’” Dibelius, Studies in the Acts of the Apostles (Scribner's, 1956), 39 explains that these objects could very well have been constructed in order to avoid the wrath of a god due to a lack of praise or homage.

Herodotus expresses similar concerns if one does not offer the proper respect to a god; see 6.105. Haenchen, The Acts of the Apostles, 521 is quite skeptical of the inscription’s existence. He asserts that there is no archeological evidence for the inscription, and he suggests that the literary support does not corroborate Acts’ claim. Hugo Hepding uncovered an inscription dating approximately to the second-century, which reads: θεοις αγ… καπιτ[ων] δαδουχο[ς]. From this, Haenchen posits that “the supplement theois agnwstois is highly improbable.” Haenchen discredited the accounts of Pausanias and Philostratus, stating “Luke probably knew from some handbook like that of Pausanias that there were ‘altars to unknown gods’ in Athens, and concluded that the individual altars bore the inscription ἀγνώστῳ θεῷ.” Although not conclusive, Pervo (Acts, 426) states, “writers in antiquity were likely to prefer literary tradition to personal observation.” This does not prove that Luke had been to Athens, but it at least shows that Haenchen’s skepticism needs to be managed.

Haenchen, The Acts of the Apostles, 522 holds that this verse has Old Testament sentiments, but the addition of κόσµος renders the statement more Greco-Roman. Dibelius, Studies in the Acts of the Apostles, 41, though, claims that this idea falls more in line with Old Testament style: “The affirmation of God as Creator belongs to the Old Testament; but it is a Hellenistic, rather than Old Testament usage, when the first phrase included the word κόσµος, whereas the Old Testament would speak of heaven and earth.”

Concerning the idol polemic (v. 29), there is more agreement amongst scholars for the Old Testament parallel. Gerd Lüdemann, Early Christianity According to the Traditions in Acts (Fortress, 1984, 191 and F.F. Bruce, The Book of the Acts, 340 note the LXX parallels here (Is 44:9–20 and Ps 115/LXX 114) as does Dibelius, Studies in the Acts of the Apostles, 44, who wrote, “attention has rightly been drawn to the fact that Deutero-Isaiah’s repeated mocking at idols conceals an unexpressed conception of a God who has no need of help.” Haenchen, The Acts of the Apostles, 525, though, astutely showed that Paul is essentially preaching to the choir; he wrote, “to the philosophers who were being addressed, this polemic would of course have offered nothing new: it hit only Greek popular religion and not the enlightened philosophical Hellenism.”

This discussion will not be had in full here; Johnson, The Acts of the Apostles, 316 reveals, “It is possible that Luke is alluding to a poem attributed to the Cretan poet Epimenides, one of the seven sages of Greece (Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Philosophers 1:109–115), possibly the same poem cited by Paul in Titus 1:12. It is not certain that Luke intended this to be a direct quotation, and the precise form of the line in Epimenides (if such it was) is not known.” Bruce, The Book of Acts, 339 provides a quotation from a ninth-century, Syriac commentator Isho’dad with an explanation whence the citation possibly arose.

Pervo, Acts, 439.

See Haenchen, The Acts of the Apostles, 525; he claims, “The quotation (Aratus, Phaenomena 5) stands as proof in the same way as biblical quotations in the other speeches of Acts. What Luke sees expressed in it may be deduced from Lk. 3.38: here God is denoted as the father of Adam, although nothing more is intended than that he created Adam.”

Schröter, From Jesus to the New Testament, 52.

I will not explore this aspect of the speech since space is limited. As Parsenios, Departure and Consolation, 4 states, “In classical literature, the death of Socrates in Plato’s Phaedo is the model farewell text, and, as in the case of Moses, Socrates’ example is copied in numerous later texts,” but he further goes on to claim that the connections are typically “superficial.” Be that as it may, since this discourse can be compared to Christ’s farewell discourse in Luke 22, consult, as Parsenios also does, William Kurz, “Luke 22:14–38 and Greco-Roman and Biblical Farewell Addresses,” JBL 104 (1985): 251–268. He also draws the reader’s attention to F. Segovia, The Farewell of the Word (Fortress, 1991).

This is by far the longest introduction present in the speeches examined thus far. The reason for including so many verses is due to the syntax of the initial sentence. V. 20 picks up right where 19 ends, indicating the two are connected, and the thought continues through v. 21.

By apology, I mean in the Platonic sense.

On account of numerous factors, Pervo, Acts, 516 denies the authenticity of this speech because it exemplifies the author’s style: “The scene of the address in Melitus portrays a situation not found in the undisputed epistles or elsewhere in Acts, for it is an address to Christian leaders.”

As Parsons, Acts, 291 observes, “Given the fact that the audience is well known to him, Paul dispenses with the expected exordium (otherwise designed to curry the favor of the audience) and moves directly into a narratio.”

onsider Plutarch, On Praising Oneself Inoffensively, 542B–C. Praise self and audience. Ascribe honor to God/Chance (Holy Spirit in Acts).

With respect to v. 20, Pervo, Acts, 520 states, “The guiding concept is that which is preferable (τὸ σύµφερον), a theme of deliberative rhetoric used in the Corinthian correspondence. Luke uses the language of Paul the pastor, that is, the language of the epistles.” Just prior to this, Pervo lists a number of parallels between this speech and the Pauline corpus.

One could argue this speech is similar to the farewell discourses in John’s Gospel because Paul knows that he is destined for death. Also, Johnson, The Acts of the Apostles, 361 expresses similar sentiments, claiming, “As in the Gospel's ‘journey narrative,’ the name Jerusalem recurs with great frequency in this part of the story (19:1, 21; 20:16, 22; 21:4, 15, 17).”

Parsons, Acts, 292 also reveals the importance of this verse for its relation to the Pauline corpus wherein it discusses the Gospel was intended for both Jew and Greek (Rom 1:16; 10:12; 1 Cor 1:24; 9:20; 10:32; 12:13; Gal 3:28; Col 3:11). Paul is willingly going to his death, as Socrates did in Phaedo. Seneca (Letter 24.4 and 70.9) mentions the willing death of Socrates. See also Epictetus, Diss, 3.24.77. Parsenios, Departure and Consolation, 90–109 has a lengthy study on Greco-Roman literature that discusses consolation, as does the first chapter.

So also Gaventa, Acts, 283.

See Gaventa, Acts, 286.

In reference to Paul working with his own hands, Haenchen Acts, 594 contends, “This is admittedly an edifying exaggeration, as II Cor. 11.9 shows: Paul by his own work could not even keep himself from want, to say nothing of caring for his companions also. Cf. I Thess. 2.9; II Thess. 3.8; I Cor. 4.12; 9.15.”

Haenchen Acts, 594–595 reveals a number of Greco-Roman parallels to the phrase.

Pervo, Acts, 528–529.

See J. D. G. Dunn, “Jesus Tradition in Paul,” in The Christ and the Spirit (Eerdmans, 1998).

The historicity of plays was an underdeveloped exploration in this paper. I chose to limit the discussion to Clouds and Socrates because it was the most direct connection. Epic poetry, romances, philosophical dialogues, farewell discourses (honorable deaths), rhetorical handbooks, and the orators are just a handful of genres that may contain promising information for our current study. Paul’s speech before the Ephesians could have been developed to a much larger degree because it appears to resemble a deliberative speech while also displaying features of a farewell discourse, but time did not permit a thorough explanation. The apologies at the end of the book also exhibit Paul’s adaptability; there may be connections with ancient apologies. I have merely scratched the surface of the insurmountable parallels that exist, and there is much left to explore.

I believe this further discredits Pervo’s claim. If the message in the speeches is for the community alone, why repeat the same message ad nauseum? It makes better sense of the data to assume that Luke is conveying a thought through a historically reliable account of the Early Church.

A. P. Norman, “Telling it like it Was: Historical Narratives on their own Terms,” in The History and Narrative Reader (Routledge, 2001), 191.

J.R.R. Tolkien. The Hobbit (New York: Ballantine, 1973). Peter Jackson expressed Tolkien’s sentiment when he added to Gandalf’s discussion with Bilbo, “Well, all good stories deserve embellishment. You'll have a tale or two to tell of your own when you come back.” Jackson’s representation of Tolkien’s playful tale on the silver screen also represents the interpretive elements of retelling a myth, story, or historical event.

This does not mean that the biblical scholar can disregard these historical hiccups. These should be assessed and examined; to dismiss these divergences would be irresponsible. Ultimately, though, the critic should take the picture as a whole into view and determine why this inconsistency exists.