Interesting Features of Ezekiel the Tragedian’s "Exagōgē"

With an Introduction to Second Temple Monotheism & NT Christology—Exalted Figures in the Jewish Pseudepigrapha, the Date of Passover

Introduction

This is a companion piece to a recent translation I published of Ezekiel the Tragedian’s Exagōgē and a more fleshed out document of a presentation I gave on the play. The focus will be on two specific sections: Moses’s Dream and the significance of Passover (the date), and how these relate to early Christian developments, specifically Christology. The tragedy will serve, more or less, as a springboard for discussing some features of the Gospels.

Prior to analyzing the significance of the Exagōgē, we must establish a basic understanding of Jewish monotheism during the Second Temple Period—from the destruction of the Temple (586BC), to its rebuilding (538BC), up to the destruction of the second (70AD)—and what Christology is. How monotheistic was Jewish monotheism at the time? How could the Messiah become God within a Jewish movement?

Second Temple Jewish Monotheism

In Judaism, the divine identity can most easily and explicitly be expressed through the opening statement of the Shema (Heb. שׁמע, “hear”): “Hear, O Israel, the Lord (YHWH) is our God; the Lord (YHWH) is one” (Deut. 6:4, KSV). This is a powerful monotheistic claim which established YHWH as the one God of Israel who is worthy of worship, for it is he alone whom “you shall love… with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might” (Deut. 6:5). He is the creator of the universe, and he is the God of history.1 The recitation of the Shema was a long established ritual performed daily during the Second Temple period.2

Richard Bauckham adds that the Decalogue (Exod. 20:2–6; Deut. 5:6–10) was recited alongside the Shema, concluding that the daily repetition of these passages asserts “the absolute uniqueness of YHWH as the one and only God.”3 That being the case, there should be little doubt that first century Jews would be fully aware of these verses, and they played a significant role in their theology, specifically their view of God—as one. The Jewish conceptualization of the divine identity was strict, which would leave no room for the worship of other gods except for YHWH alone (Deut. 5:6,7)—or does it? How then could Jesus be considered God in early Christianity?

Although Jewish monotheistic thought in the Second Temple Period appears extremely restrictive, there is contention as to how exclusive this monotheism truly was. John Collins inquires,

By nearly all accounts, by the end of the first century C.E., strict monotheism had long been one of the pillars of Judaism... how was it possible for first-century C.E. Jews to accept this man Jesus as the preexistent Son of God and still believe, as they surely did, that they were not violating traditional Jewish monotheism?4

Because early Christians were able to incorporate Jesus into the divine identity, Collins argues that the Jewish monotheism during the Second Temple period was not as cut and dried as one might believe. Even within early Christian documents, e.g., Paul's epistles and the Gospels, there is plenty of subordination language seemingly to preserve their Jewish monotheism—1 Cor 15:28; John 14:28. Such passages have generated much speculation on how these authors understood Jesus’s relationship to God.5

During the Hellenistic period,—death of Alexander the Great (323 BC) up to the rise to prominence of Rome (31 BC)—several types of quasi-divine figures surfaced within Jewish compositions, which complicates the perspective of an absolutely strict monotheism. Collins lists three separate categories of characters present in these texts, and each functions as divine agents similar to Jesus in New Testament traditions:

Angelic Figures

Exalted Human Beings

Abstract Figures—e.g., personified Wisdom and the Word.6

The existence of these figures complicates the traditional understanding of Jewish monotheism. Collins further claims that these characters’ limited participation in the divine identity made it easier for Jesus’s status to elevate over time.7

For our purposes, we will examine only exalted humans. The germ of this thought is certainly biblical; consider the Son of Man figure in Dan 7:9, 13–14 (RSV),

|9| thrones were placed/ and one that was ancient of days took his seat;

his raiment was white as snow,/ and the hair of his head like pure wool;

his throne was fiery flames,/ its wheels were burning fire...

|13| ...and behold, with the clouds of heaven/ there came one like a son of man,

and he came to the Ancient of Days/ and was presented before him.

|14| And to him was given dominion/ and glory and kingdom,

that all peoples, nations, and languages/ should serve him;

his dominion is an everlasting dominion,/ which shall not pass away,

and his kingdom one/ that shall not be destroyed.

Notice how God—the Ancient of Days—is robed in white and sits upon a throne. He calls forth a human—a Son of Man8—to share in his dominion and glory over all the world, yet this mortal does not take God’s throne or scepter. In the extra-Jewish literature that was produced before/around Paul and the Gospels, there are significant expansions of this thought. Now, regardless of the date of Daniel, the work is just prior to or contemporaneous with many Jewish Pseudepigraphical works that also contain such exalted figures, which underscores the significance of this development within Judaism for nascent Christianity.

Christology

The Christology present in the New Testament is varied and is in no way systematic. This is largely a result of the New Testament being a collection of various writings produced over an extended stretch of time, written by distinct authors with different emphases and perspectives. So, what is Christology? Concisely, Raymond Brown defined “Christology [as the] discuss[ion of] how Jesus came to be called the Messiah or Christ and what was meant by that designation… [It] discusses any evaluation of Jesus in respect to who he was and the role he played in the divine plan.”9 That does not mean, however, that a fully developed Christology emerged immediately after the church was formed. The Christology of the New Testament evolved over time, but the temporal component of this process is highly contentious in New Testament scholarship—was the phenomenon, i.e. Jesus’s divinity (high Christology), due to Gentile inclusion and Hellenism,10 or was it a product of early Jewish Christian communities?11

To delve into this answer would diverge too greatly from the purpose of this publication, but I will comment that the NT authors are not exactly unified on this thought. For instance, Mark is considered to have a low Christology since the text is not clear on Jesus’s relationship with God, whereas John is more explicit.12 There is great disagreement within the scholarly community concerning when exactly early Christians began worshiping Jesus as God; Dunn writes,

So our central question [did the earliest Christians worship Jesus?] can indeed be answered negatively, and perhaps it should be. But not if the result is a far less adequate worship of God. For the worship that really constitutes Christianity and forms its distinctive contribution to the dialogue of the religions, is the worship of God as enabled by Jesus, the worship of God as revealed in and through Jesus. Christianity remains a monotheistic faith. The only one to be worshipped is the one God.13

Contrarily, others argue for the early inclusion of Jesus in the divine identity, such as Lary Hurtado14 and Richard Bauckam,15 believing that even the earliest Christians were already worshiping Jesus.

Why is the Exagōgē Significant?

In the introduction to my translation, I discussed the work’s importance for it being the only extant Jewish hellenistic tragedy, but there is more that can be said. As for Christianity and the developing monotheism within Second Temple Judaism, it reveals quite a lot in the case of Moses’s Dream. The discourse between God and Moses concerning Passover will be the final exploration, specifically as a segue for discussing the date of Jesus’s crucifixion.

Moses Sitting upon God’s Throne: The Dream Sequence

The most shocking deviation from the biblical account must be Moses’s dream, for his ascent to God’s throne should appear scandalous. It is God alone who is able to judge and rule over his creation, but it is not entirely out of the question for someone to do that on his behalf—cp. Dan 7:9ff. The striking detail is God relinquishing his scepter & crown and allowing Moses to sit on his throne (KSV):

|68| I dreamt of a great throne on the top of Mount Sinai,

|69| which was up to the folds of heaven,

|70| upon which an illustrious man sat,

|71| who possessed a crown and a great scepter in his hand,

|72| specifically his left. And with his right, to me

|73| he beckoned. And I stood before his throne;

|74| and he handed over the scepter to me, and upon the great throne

|75| he said to sit. And he gave to me the royal

|76| crown and he departed from the throne.

|77| And I saw the entire round world

|78| and beneath the earth and above the heavens,

|79| and before me, a plethora of stars toward my knees

|80| fell, and I numbered them all.

|81| And they were led (before me) akin to a battalion of men.

|82| Then, I awoke from my slumber and was afraid.

The text reads quite similarly to that in Daniel and the Ancient of Days—of a dignified man, God, who sits upon his throne over the world. Although more explicit in Daniel, the Exagōgē clearly depicts a scene of one ruling from on high. Moses taking the scepter and crown, then sitting upon God’s throne, though, are privileges that even the Son of Man was not able to enjoy. Regardless, both are exalted figures who infringe upon the divine identity—these two are performing deeds that belong to the divine prerogative.

The counting of the stars, too, is an action conducted only by God. Consider Ps 147:4 (RSV),

He determines the number of the stars,

he gives to all of them their names.

Likewise, Moses is given this same ability. He is an exalted figure who is encroaching on the divine powers; he is performing deeds that God alone is entitled to do:

Seated upon a heavenly throne

Holding in hand God’s scepter, wearing God’s crown

Ruling, having dominion (albeit, implied)

Counting of the stars

The throne is a seat of power, one of dominion and judgment, as can be witnessed in the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha (OTP):16

Exalted Figure

T. Ab. 12:2–13, The Commander-in-chief said, “Do you see, all-pious Abraham, the frightful man who is seated on the throne? This is the son of Adam, the first-formed, who is called Abel, whom Cain the wicked killed. And he sits here to judge the entire creation, examining both righteous and sinners.

God

1 En. 14:18–20, And I observed and saw inside it a lofty throne... and from beneath the throne were issuing streams of flaming fire. It was difficult to look at it. And the Great Glory was sitting upon it—as for his gown, which was shining more brightly than the sun, it was whiter than any snow.17

It is most common for God to be on his heavenly throne, but in the Testament of Abraham, another exalted human—Abel—shares in the divine prerogative. We can see in these few examples that there has already been an expansion of who can perform divine actions—critical developments in Jewish thought for what humans are permitted to do.

This is not dissimilar to claims of Jesus enthroned, empowered, or judging others in the New Testament; consider:

1 Cor 15:24–27 (RSV), |24| Then comes the end, when [Jesus] delivers the kingdom to God the Father after destroying every rule and every authority and power. |25| For he must reign until he has put all his enemies under his feet. |26| The last enemy to be destroyed is death. |27| “For God has put all things in subjection under his feet.” But when it says, “All things are put in subjection under him,” it is plain that he is excepted who put all things under him. |28| When all things are subjected to him, then the Son himself will also be subjected to him who put all things under him, that God may be everything to every one.

Mark 14:62 (RSV), And Jesus said, “I am; and you will see the Son of man seated at the right hand of Power, and coming with the clouds of heaven.”

Matt 19:28//Luke 22:28–30 (RSV), Jesus said to them, “Truly, I say to you, in the new world, when the Son of man shall sit on his glorious throne, you who have followed me will also sit on twelve thrones, judging the twelve tribes of Israel.

In each of these instances, Jesus is associated with the divine authority, to rule and subjugate; though, this exalted position is curtailed, at least in 1 Corinthians and Mark. We can say with some certainty that these developments in Jewish thought paved the way for Jesus’s inclusion in the divine identity. For, based on the Hebrew Bible alone, it would be more difficult to accept a figure who performs godly actions.

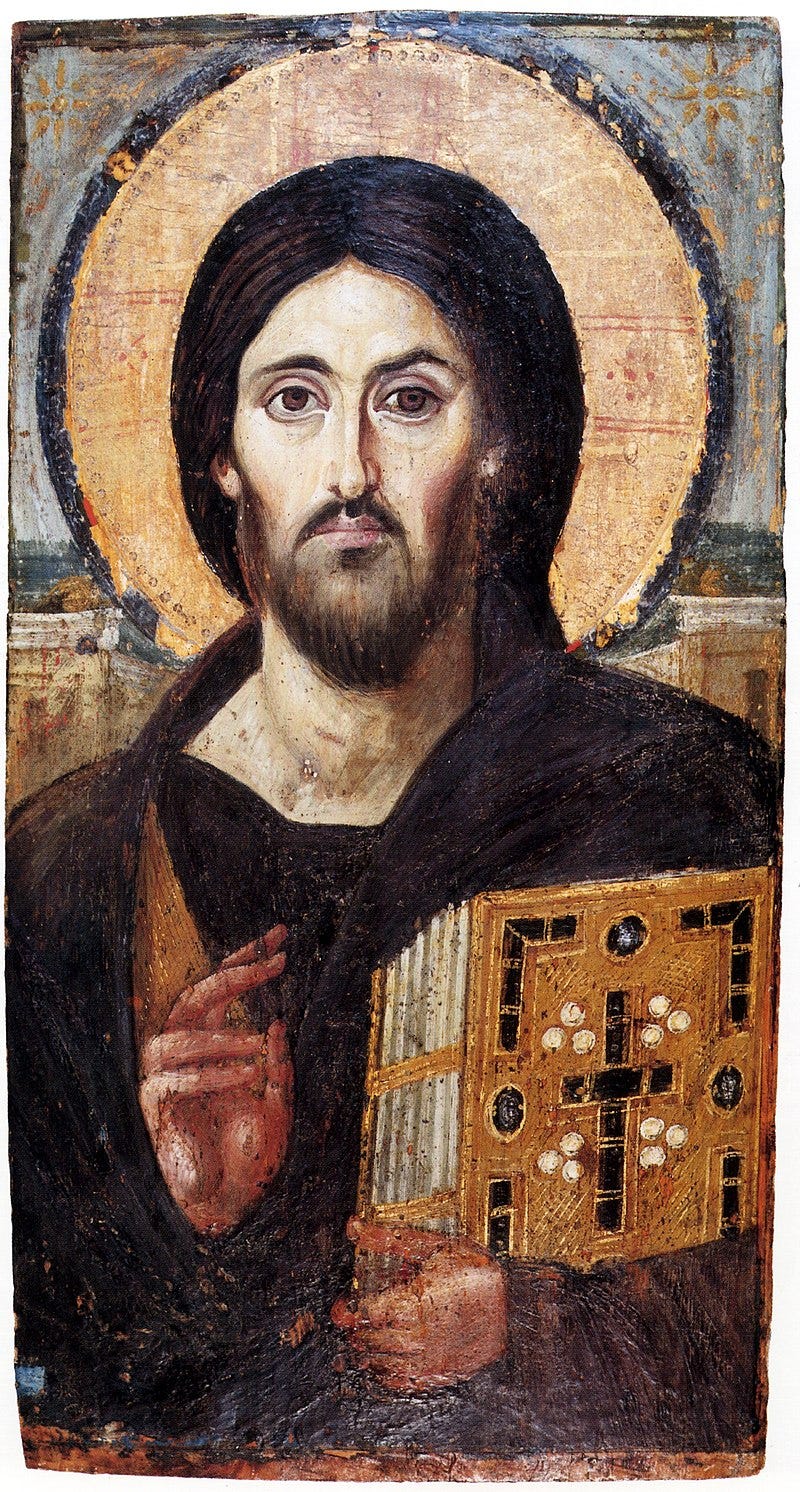

Aside from the textual parallels, it is fascinating to note developments in iconography and Christian art, which depict Jesus enthroned:

Passover (Pesaḥ): Exodus, Exagōgē, Jubilees, and the Gospels

Instrumental for both Jews and Christians, the Passover in Exodus is a major event that restructured time for Judaism,—this festival is to mark the beginning of the year—and the celebration of the Hebrews’ liberation frames the most critical event in Christianity—the death of the Son of God, the Messiah. It should not be surprising, then, that the understanding of this narrative evolved over time.

The original account, Exod 12:1–28, has a dual function: (1) explain in the narrative what the Hebrews did before escaping Egypt and sojourning in the desert and (2) provide an etiology for how Pesaḥ (Passover, Heb. פֶּסַח; Gk. πάσχα, pascha) is celebrated and its significance.18 We will explore but a few of these details and how they developed:

|1| The Lord said to Moses and Aaron in the land of Egypt, |2| “This month shall be for you the beginning of months; it shall be the first month of the year for you. |3| Tell all the congregation of Israel that on the tenth day of this month they shall take every man a lamb according to their fathers’ houses, a lamb for a household...

|5| Your lamb shall be without blemish, a male a year old; you shall take it from the sheep or from the goats; |6| and you shall keep it until the fourteenth day of this month, when the whole assembly of the congregation of Israel shall kill their lambs in the evening...

|14| “This day shall be for you a memorial day, and you shall keep it as a feast to the Lord; throughout your generations you shall observe it as an ordinance for ever...

I have highlighted the key elements in these verses: (1) the restructuring of time; (2) the selection of an unblemished lamb; (3) the sacrifice should be on the 14th day of the month (Nisan—not just a car brand, but the first month in the Jewish calendar); and (4) this meal will serve as a memorial, practiced within the community forever. There are other key elements of the story that I skipped over,—e.g., the hyssop branch used to paint blood over the door—but we are focusing only on these aspects in development.

Passover (Pesaḥ) in Ezekiel’s Exagōgē

Ezekiel’s tragedy is the most pedestrian of the texts that will be explored because it offers little expansion, unlike the exaltation of Moses above. Rather, it mostly follows the account in Exodus, but in poetic form:

|175| During this month, among the Hebrew men, (each) will take

|176| according to their family sheep and calves from among the cattle

|177| who are unblemished, on the tenth day. And let each reserve (their animal) until

|178| (the light) shines on the fourteenth day; and towards evening

|179| sacrifice (the animal), and (consume) the entire roasted (animal), with the innards—

|180| in this manner eat them...

|184| and he will summon everyone. And whenever you conduct your sacrifices,

|185| take in hand a bundle of hyssop branches,

|186| dip (them) into the blood, and dab (them) on the two doorposts,

|187| so that Death might pass over the Hebrews.

|188| And you will observe this [Festival] to the Master,

|189| Seven Days of Unleavened Bread; and leaven will not be consumed.

|190| For (my people) will be released from these evils,

|191| and God is providing an exodus (for you) this month.

|192| And this is the beginning of your month and time.

A much truncated version, this speech from God to Moses highlights the important features of Exod 12:1–28. What should stand out most is the selection of the lamb on the fourteenth day (of Nisan) and the celebration is to be their first month of the year. If anything, the tragedy highlights the significance of the festival, retaining key elements that all Jews would know and celebrate yearly.

Passover (Pesaḥ) in Jubilees

Previously, I translated a section of Jubilees on the near sacrifice of Isaac (the ‘Aqedah, the Binding of Isaac), which is similar to Ezekiel’s tragedy; it is a retelling of a famous narrative in the Hebrew Bible, but there are additional features and commentary injected into the text. Now, you may think, what does Isaac’s sacrifice have to do with Pesaḥ (Passover)?

In this work of re-written Bible, the author framed the narrative at the time of Passover. The beginning of the section states, “During the seventh week, in the first year in the first month—in this Jubilee—on the twelfth of this month, there were voices in heaven concerning Abraham” (Jubilees 17.15). Recall that in Exodus and the Exagōgē, the authors made it clear that the calendar would be arranged so that the first month of the year would contain the celebration of Pesaḥ (Passover). So here, the temporal framework has been set; the events have started on the 12th day of the first month (Nisan).

At the retelling of the ‘Aqedah, the text states,

And (Abraham) arose at daybreak, and he loaded his donkey. He took two servants with him and his son Isaac. He split the wood for the sacrifice, and he came to the place on the third day. He saw the place from afar. (Jubilees 18.3)

The journey begins on the 12th of the first month (Nisan), they travel day 2 (13 Nisan), and they arrive on the “third day” (14 Nisan)—the day when the Passover lamb was to be sacrificed, the first born, unblemished. The text highlights the parallel, concluding,

And he celebrated (habitually) this festival every year for seven days with rejoicing, and he called it “the Festival of God” according to the seven days during which he went and returned in peace. (Jubilees 18.18).

Passover begins the Festival of Unleavened Bread (cp. line 189 of Exagōgē) which also lasts 7 days. So, here, there is a clear calendrical parallel between the Binding of Isaac and the Passover sacrifice.19

It may appear odd that Passover and the Sacrifice of Isaac have been joined together. But, Jubilees is not the only text to draw the connection. The Palestinian Targum on Exodus 12:42 discusses “four nights,” explaining how four major events for Judaism all occurred on the same day, 14 Nisan: (1) Creation; (2) the ‘Aqedah (binding of Isaac); (3) the flight from Egypt/Pesaḥ; and (4) the end of the world/the coming of the Messiah.

Passover (Pesaḥ, Pascha) in the Gospels

The most apparent reference to Passover in the Gospels is at Jesus’s death, for it happens during this festival, but is there agreement on when his death occurs in the Synoptics—Matthew, Mark, Luke—and John? In short, the Synoptic Gospels and John disagree on the day when Jesus was sacrificed and died. The contention over the dating of Christ's actual crucifixion is due to the conflicting timelines. Some commentators have attempted to harmonize the accounts, asserting that Matthew, Mark, and Luke are reckoning time based on a different calendar than John,20 but the text betrays this hypothesis.

Matt 26:17, 19 (RSV), |17| Now on the first day of Unleavened Bread the disciples came to Jesus, saying, “Where will you have us prepare for you to eat the passover?...” |19| And the disciples did as Jesus had directed them, and they prepared the passover.

Mark 14:12, 16 (RSV), |12| And on the first day of Unleavened Bread, when they sacrificed the passover lamb, his disciples said to him, “Where will you have us go and prepare for you to eat the passover?...” |16| And the disciples set out and went to the city, and found it as he had told them; and they prepared the passover.

Luke 22:7, 13 (RSV), |7| Then came the day of Unleavened Bread, on which the passover lamb had to be sacrificed. |13| And they went, and found it as he had told them; and they prepared the passover.

John 13:1; 19:14, 31 (RSV), |13:1| Now before the feast of the Passover, when Jesus knew that his hour had come to depart out of this world to the Father... |19:14| Now it was the day of Preparation of the Passover; it was about the sixth hour. He said to the Jews, “Behold your King!...” |31| [after Jesus’ death] Since it was the day of Preparation, in order to prevent the bodies from remaining on the cross on the sabbath (for that sabbath was a high day)...

Observe that the synoptic tradition contains more or less the same rendering in the initial verse: it was the first day of the Feast of Unleavened Bread when the paschal lamb was sacrificed; Matthew lacks the second phrase, though. From these passages, we can discern that the chronologies are conflicting; in the synoptics, the “Last Supper” occurred on Pascha whereas John 19:1 clearly states that it was the Day of Preparation for the Pascha (παρασκευὴ τοῦ πάσχα) when Jesus was crucified.21 In the Synoptics, the Last Supper is a Passover Meal, whereas in John, it is not.

The history of interpretation for John 19:14 has varied on this point, since many translators have attempted to assess this minor hiccup. Theodore of Mopseustia (Commentary on John 7.19.14) mentions that some call the gospels into question on this point, but the focus concerns the time at which Christ was crucified rather than on the date, as does Augustine (Tractates on the Gospel of John 117.1). Eusebius of Caesarea (Minor Supplements to Question to Marinus 4) chalks it up as a scribal error. Peter of Alexandria (Fragment 1.7) affirms that “Jesus did not eat of the lamb, but he himself suffered as the true Lamb in the Paschal feast” (14 Nisan).22 Most modern commentators concede that John's crucifixion narrative differs from the synoptics and that the narrative event occurred on the Day of Preparation when the lambs were sacrificed.23

Strikingly, I have found zero commentators who extensively argue why John differs from the synoptics. It is obvious that this shift is on theological grounds, but I will write about this later when discussing an Isaac typology in the Gospel of John—there is significance as to what day Christ was sacrificed. Regardless, both accounts associate Christ's Passion with the Pascha, similar to Isaac in Jubilees.

As for christological significance, it is worth noting that Jesus is not paralleled with God in his death. Rather, he is the opposite of divine, for he is the sacrificial lamb—especially underscored in John (e.g., “Lamb of God” language). I do argue that in Mark this ironic coronation on the cross is representative of a high Christology,—briefly here; I plan to upload a more extensive entry later—but it is certainly not of the same kind as Moses in the Exagōgē. Jesus is not explicitly in his glory, surrounded by angels, judging from a throne.

Conclusion

It cannot be overstated how significant the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha is for understanding early Christianity. To neglect these texts along with the Deutero-Canonical Books (or, “Apocrypha”) would be a great disservice to our understanding of thought in the nascent Church. If one were to believe that only the canonical books of the OT had influence on early Christian authors, that would be myopic. Jewish thought was not stagnant for over 400 years; it continued to develop from the end of the prophets up to the composition of Paul’s first epistle, so it is critical to have an appreciation for and comprehension of this corpus of works.

In turn, these evolutions of belief are paramount since much of this became foundational for early Christian thought, as was illustrated in our exploration of Christology. It is impossible for us to know precisely what early Christians were reading, but we can at least observe veins of thought that potentially influenced the church.

My next post will likely be on Mark 6:52,—“And [the disciples] were utterly astounded, for they did not understand about the [bread] (συνῆκαν ἐπὶ τοῖς ἄρτοις), but their hearts were hardened (ἡ καρδία πεπωρωμένη)” (6:52)—since I have been working on this thesis for quite some time now. I explore the significance of the Exodus—specifically bread from heaven, hardened hearts, and misunderstanding—in relation to chs. 6–8 to unravel the Messianic Secret. This explanatory verse is bizarre because what does bread have to do with understanding Jesus’s miraculous walking on water?

If you want to read more of my translations or explore the Jewish Pseudepigrapha and topics on the New Testament, would you kindly subscribe?

These are unique qualities of the God of Israel—he alone creates; he alone influences history for his end.

See, J. Dunn, “Was Jesus a Monotheist? A Contribution to the Discussion of Christian Monotheism'' in Early Jewish and Christian Monotheism; ed. L. Stuckenbruck & W. North (London: T&T Clark, 2004), 105.

R. Bauckham, Jesus and the God of Israel (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2008), 5.

J. Collins, Encounters with Biblical Theology (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2005), 179.

A topic I will expound upon later.

Collins, Encounters, 180–186 has a more fleshed out description of these groups.

Collins, Encounters, 187.

In the case of Daniel, the phrase, “son of man,” just means a human being, a mortal. This title eventually develops messianic overtones, but it is not present here.

R. Brown, An Introduction to New Testament Christology (New York: Paulist, 1994).

E.g., W. Bousset, Kyrios Christos, (Nashville: Abingdon, 1970).

E.g., L. Hurtado, How on Earth did Jesus become a God? (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005).

That is not to say that Mark truly has a low Christology. I disagree with this assessment of the Gospel, but you have to dig through the text far more to unearth a higher Christology. Nowhere does anyone exclaim, “My Lord and my God!”

J. Dunn, Did the First Christians Worship Jesus? (Louisville: Westminster, 2010), 151.

L. Hurtado, Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003).

R. Bauckham, God Crucified: Monotheism and Christology in the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1999).

God seated upon a throne in heaven is not unique in the OTP, Gk. Apoc. Ezra 4.9; T. Levi 5:1; Apoc. Mos. 37:4; 4 Mac 17:17–18.

Space does not permit a fuller discussion, but the description of the clothing in 1 Enoch and the Exagōgē resemble Jesus’s in the Transfiguration.

A note on pronunciation: a dotted h—an “h” with a dot under it—is pronounced like the “ch” in “Bach.”

There are more parallels other than just temporal for making this association. But, space does not permit a full explanation, which I plan to do in a larger project on the parallels between Jesus and Isaac in the Gospel of John.

E.g., J. Boice, The Gospel of John (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1985), 1329. L. Morris, The Gospel According to John (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1995), 684–695.

J. VanderKam, “Passover,” in Encyclopedia of the Dead Sea Scrolls, 2 vols.; ed. L. Schiffman & J. VanderKam (New York: Oxford, 2000), 2:637 writes, “In John, the Last Supper is eaten the night before Passover, while Jesus is crucified at the time when the Passover lambs were slaughtered in the Temple (Jn. 13.1, 18.28, 18.39, 19.14).”

He further states, “‘…And it was the preparation of the Passover, and about the third hour,’ as the correct books render it and the copy itself that was written by the hand of the Evangelist, which by divine grace has been preserved in the most holy church of Ephesus and is there adored by the faithful… Rather, as I have said, he himself, as the true Lamb, was sacrificed for us in the feast of the typical Passover on the day of the preparation, the fourteenth of the first lunar month.”

F. Godet, Commentary on the Gospel of John, 2 vols.; trans. T. Dwight (London: Funk & Wagnalls, 1893), 2:379; B. Westcott, The Gospel According to St. John (London: John Murray, 1882), 2:272; R. Schnakenburg, The Gospel According to St. John; trans. D. Smith & G. Kon (New York: Crossroad, 1982), 3:264–65. E. Haenchen, A Commentary on the Gospel of John, 2 vols; trans. R. Funk (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1984), 2:183; F. Moloney, The Gospel of John (Collegeville: Liturgical, 1998), 496; D. Smith, John (Nashville: Abingdon, 1999), 350.