Of Wine and Kingdom—Was Jesus Wrong in Mark 9:1?

An Exegetical Analysis of Christ’s (Ironic) Coronation & Enthronement and the Manifestation of the Kingdom of God in the Gospel of Mark

This is an exegetical probe I have wanted to write up for quite some time: when is the Kingdom of God manifested in the Gospel according to Mark?—I mentioned it briefly in my topical outline of Mark, note 18. The germ of this inquiry is buried in the conclusion of Jesus's first Passion Prediction in Mark 9:1, which has a bold claim that seemingly goes unfulfilled in the narrative:

And [Jesus] said to them, “Truly, I say to you, there are some standing here who will not taste death before they see that the kingdom of God has come with power.”

There is no explicit instance in Mark where the Kingdom of God is revealed as having come, much less “with power” (ἐν δυνάμει, en dunamei). Rather, the Gospel progresses through Jesus’s ministry, building towards the climax with his triumphal entry into Jerusalem,—replete with Christological, Messianic, and Monarchical overtones—but then Jesus is soon arrested, crucified, and killed, with no manifestation of the resurrected Lord,1 assuming that would be the moment of the Kingdom arriving, an image of glory and power. Nothing about the conclusion of the Gospel reveals the Kingdom of God in power; in fact, it reflects the opposite: a failed messianic figure expired upon a cross, a common punishment for usurpers and insurrectionists.

Yes, there is an empty tomb and a promise of meeting in Galilee (16:6–7), but if one ruminates on the Gospel’s ending, when is the Kingdom of God ushered in? Even in the longer ending of Mark, there is no clear occurrence; perhaps this was the intent of the one who added 16:19,

So then the Lord Jesus, after he had spoken to them, was taken up into heaven, and sat down at the right hand of God.

That said, it is murky at best; it is thematically/stylistically inconsistent for the Gospel on a deeper level. This opaque narratorial statement is not sufficient,—nor is it original—so was Jesus wrong, misleading, or outright deceitful in Mark 9:1?

This jarring possibility might be dyspeptic. If there is no coming of the Kingdom recorded in Mark, then the logical conclusion must be that Jesus hoodwinked the disciples or was simply incorrect. Afterall, those present are long dead and buried.

Adela Collins, Mark, 413 comments:

Thus 9:1 should be interpreted as referring to the coming of the Son of Man. It is at that time that the kingdom of God will be manifested. The claim that some who heard Jesus (either those who heard the historical Jesus or those who heard him as members of the audience of Mark) would live until the coming of the Son of Man is evidence of the imminent expectation of that event on the part of the author of Mark.

Morna Hooker, The Gospel according to St. Mark, 211 adds:

Many of the contorted explanations which exegetes have managed to twist out of these words have been based on the conviction that Jesus could not have been mistaken, and that some fulfilment of his words must therefore be found in history. The coming of the Kingdom has been identified with such varied events as the resurrection, the gift of the Holy Spirit, and the fall of Jerusalem. It is difficult to see how any of these can convincingly be described as the final manifestation of God’s Kingdom; the fact that an event is linked with the power of God does not mean that it is therefore to be identified with his Kingdom.

The majority of scholars attempt to position this either as a glitch and Jesus was wrong; this is a comment for the community, and it was wrong—that is, the phrase does not go back to the historical Jesus and is a contrivance by Mark—or, more positively, it is anticipating the next scene, the Transfiguration—but, this explanation has its own problems.2

These conclusions are largely contingent on form criticism and community level readings—two speculative fields that rely on premises that can neither be confirmed or denied. As such, I prefer to approach the Gospel through a narrative critical approach—what is the message of the text in its completed form, avoiding the presumption that some verses are for the author's hypothetical “community,” which may not have even existed.3 Most commentators have twisted themselves into a pretzel in order to explain what exactly Mark meant, avoiding how the verse functions on the narrative level.

Mark is far too clever, though, to leave a critical chord such as this unresolved; there is, in fact, a resolution to this niggling note in the narrative. The Kingdom of God is manifest in Mark, but it arrives not as one might expect—how Markan considering the Evangelist never conveniently elucidates any ambiguity.

Once seen through the prism of irony, subtlety, and mockery, the reader can see Mark anew and perceive the mocking coronation, ironic enthronement, and subtle ushering in of the Kingdom of God as the author intended. The Kingdom coming in power is not expressed in terms that the reader would expect, and that is the point.

One may ask, why would Mark structure his Gospel in a confusing manner that could lead to confusion and misunderstanding? That is a topic beyond the scope of this exploration, but, as a quick note, it is not incumbent upon us to explain why an ancient author composed their theological treatise as they did. All we can do now is explicate what the meaning lying beneath the words signifies.

Now, we will explore a number of pericopes and sayings that reveal how Jesus foreshadowed and fulfilled his role as the Christ and brought about the Kingdom of God. The key passages that I will present include the following,

Mark 8:31–9:1 | A Passion Prediction and Assurance

Mark 10:35–45 | A Not So Humble Request from James & John

Mark 14:22–25 | A Promise of Wine and Kingdom

Mark 14:61 | The Ironic Recognition by the High Priest

Mark 15:2 | The Ironic Recognition by the Empire

Mark 15:16–20 | The Mocking Coronation

Mark 15:21–32 | The Ironic Enthronement

Mark 15:36 | Of Wine and Kingdom

As a final comment before commencing with our exegetical exploration, I will not be detailing the monarchical or christological background underpinning the argument. These are developments that percolated for centuries prior to the first century and would take far more space than I can allow here to explain—See Joel Marcus, The Way of the Lord for an exceptional monograph on the topic.4 And, lastly, this will be a narrative critical approach, so I am exploring the internal signifiers that Mark has placed throughout.

Now, let us explore how Mark details the ushering in of the Kingdom.

A Passion Prediction and Assurance (8:31–9:1)

Mark 8:29 is part of the turning point in the Gospel where Jesus’s identity becomes clearer to the narrative audience and the reader; here Peter declares who Jesus is, in part: “You are the Christ” (σὺ εἶ ὁ χριστός, su ei ho christos). To which Jesus replies:—per the narrator—keep this to yourself. There is no declaration of praise as in Matthew’s report,

|17| Blessed are you, Simon Bar-Jona! For flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my Father who is in heaven. |18| And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the powers of death shall not prevail against it. |19| I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.

Matt 16:17–19

Jesus still commands the disciples not to spread the news,—a retention of Mark’s account—yet Jesus’s response is exceedingly positive. It expounds on and enlarges what Mark provided.

Mark, in contrast, only has Jesus nip the conversation and then declare he is about to die. He progresses to say all the chief priests and officials will denounce him,—the converse occurs, but done through ironic statements (see 14:51, 15:2, which we will discuss)—and he will be led to his death. A striking disclosure to have just after a clear christological declaration slipping from Peter’s mouth.

At first read, one might think this is an antithetical conversation to occur after such an important development in Mark’s narrative. The Passion prediction—the first of three in the Gospel (see also 9:30–32; 10:32–34)—is magnificently germane and critical at this juncture. Peter declares Jesus to be the Christ—a monarchical title, an appeal to the coming king who will restore the Kingdom (cp. 1:1ff)—and Jesus foreshadows what is to come: his (mock) enthronement (on the cross).

Peter hastily goes to silence Jesus himself, to which Christ rebukes him, stating that this must come to pass.5 A major thrust of the Gospel comes at the end of the pericope, a palliative for Jesus’ startling statement of suffering and death:

Truly, I say to you, there are some standing here who will not taste death before they see that the kingdom of God has come with power.

Mark 9:1

This statement, paired with 8:29, resonates perfectly with what follows later in the narrative. The Passion Prediction ultimately is an appeal back to Peter’s Christological claim while simultaneously pointing forward to Jesus’s Enthronement (on the cross). Jesus cannot be the Christ—as far as Mark’s Gospel is concerned—without his accompanying death.

It is worth noting, though, that the assurance is hardly reassuring. It does not negate the death of Christ; it just pairs his death with the coming of the Kingdom of God. Although, as we saw in the introduction, many commentators assume this is a post-resurrection understanding of the Jesus’s death. I disagree completely. Rather, this is a foreshadowing, a tacit explanation, of how Mark understands the crucifixion. It is not a moment of shame and defeat; it is a moment of power and victory.

This is a foundational piece to understand initially when the Kingdom of God is coming. Peter’s coincidentally accurate pronouncement lays the foundation, and Jesus expounds on what that title signifies: his death. The concluding words from Christ are a foretaste of the biting irony at the end of the Gospel.

Suffice it to say, the foundation has been laid for understanding how and when the Kingdom of God is coming. Mark has subtly laid the bricks for this narrative development, but it will become clear when we see how Jesus and others speak about the Kingdom and the Crucifixion.

A Not So Humble Request from James & John (10:35–45)

The intervening narratives that lie between Jesus’ first Passion Prediction and the Request of James and John are less significant in the development of our thesis. It is important to note, though, that there have been two additional Passion Predictions (9:30–32; 10:32–34), which further underscore the significance of the Crucifixion.

Immediately after the third prediction, James and John—clearly feeling as if they are the greatest amongst the disciples (cp. 9:33–37; they still do not understand)—make a bold request of the Christ,

Grant us to sit, one at your right hand and one at your left, in your glory (ἐν τῇ δόξῃ).

Mark 10:37

The request, ultimately, is a signifier of misunderstanding. They believe Christ’s coming into power and kingship will include earthly authority, a supplanting of Roman rule in Palestine. So, when Jesus seizes his cloak, his crown, and his scepter, seated upon his throne as King of the Jews, they wish to be in a privileged position of power: on his right and on his left.

To this inquiry, Jesus presses them and asks if they are able to drink from the cup (ποτήριον) that he drinks or participate in the baptism in which he was baptized. They ignorantly profess that they are able, not realizing what this entails. Jesus, in turn, claims they will indeed share in the cup and baptism—not as they expect, obviously; a reference to their deaths—but, as for their request, Jesus asserts,

...but to sit at my right hand or at my left is not mine to grant, but it is for those for whom it has been prepared.

Mark 10:40

Mark has peeled back another layer of what the Crucifixion is. When one first reads the Gospel, though, this sounds nonsensical. How is this a proper response to James and John? If Jesus, the Christ, has not the authority to determine who will be on his right and left, positions of power and authority, when he comes into his glory—that is, his enthronement and exaltation, seemingly—who does?

Another wrinkle that I will not expound on greatly concerns what is meant by “glory.” I tipped my hand in the previous explanation, but I understand this to be when the Christ is enthroned and the Kingdom of God is near—or, has come.

Mark, once again, has not spelled this out. Rather, he has placed subtle narrative hints that must be pieced together once the Gospel in its entirety has been heard. Consider reading the Gospel for the first time; do you know what is meant by sitting on the right and left of Jesus at any point in the narrative? It is not until the end, the climax, when Jesus is crucified that two anonymous brigands are nailed to their own crosses beside Christ.

Now, we have jumped the gun a bit here, but so far in Mark’s narrative, we can note the following:

The Gospel opens with a declaration of Jesus’s status: “The beginning of the Good News of Jesus Christ [the Son of God]”—2 monarchical titles (1:1)

Peter declares Jesus to be the Christ, the first utterance by a mortal—a monarchical title (8:29)

The first Passion Prediction, which anticipates the Cross, linked specifically with the coming of the Kingdom of God (9:1)

After a third Passion Prediction, a request from James and John results in Jesus disclosing, tacitly, that when he comes into his glory (ἐν τῇ δόξῃ), there will be 2 seated on his left and right (10:40)

Although not declared specifically by the narrator or Jesus, his glory must be a reference to the Crucifixion,6 for it is there alone that these narrative elements converge, as we will see.

A Promise of Wine & Kingdom (14:22–25)

We now come to the Last Supper, the final time that Jesus will sup with his disciples—the Passover meal. Obviously, there are numerous pericopes that help flesh out our thesis, specifically those with christological and monarchical themes, that I have skipped over,—e.g., the Triumphal Entry (Mark 11:1–11)—but we are hitting the highlights in our journey to the Cross.

After Jesus utters the Words of Institution (14:22–24) and taking up the cup (ποτήριον),7 Jesus states,

Truly, I say to you, I shall not drink again of the fruit of the vine (τοῦ γενήματος τῆς ἀμπέλου) until that day when I drink it new in the kingdom of God.

Mark 14:25

Here, we should note a number of crucial elements:

Jesus will not drink the fruit of the vine—that is, wine

Until he drinks it new in the Kingdom of God

What we have seen thus far in our study, Jesus predicts the coming of the Kingdom of God arriving prior to the death of (some) of his disciples (9:1). The Christ has just declared at his final meal with his disciples that he will not drink wine (read: a drink produced from grapes) until the Kingdom of God has come. This is of paramount importance for where we are headed exegetically.

Mark has laid the narrative groundwork for the reader to recognize when the Kingdom is in the here and now. Based on these events and subtle quips, Jesus must be

Sandwiched between two others, one on his left and one on his right (the revelation of his glory)

Drinking wine (signifying he is in the Kingdom of God)

In this situation, Jesus will have come into his glory and the Kingdom of God will be at hand.8

The Ironic Recognition by the Authorities

The next two sayings that I will discuss have to deal with establishing Jesus as a king in the narrative. These points are not as impressive for revealing the coming of the Kingdom of God based on narrative actions as predicted previously, but they do help clarify Jesus as King at the climax of the Gospel—well, ironically.

Jesus Pronounced as the Christ by the High Priest (14:51)

The Last Supper has ended, Judas has betrayed the Christ at Gethsemane,—leading to his arrest—and Jesus is brought before “the high priest; and all the chief priests and the elders and the scribes were assembled” (14:53). During the interrogation, accusations are made against Jesus, to which he remains silent.

Eventually, the High Priest speaks to Jesus himself:

Again the high priest asked him, “Are you the Christ, the Son of the Blessed?” And Jesus said, “I am; and you will see the Son of man seated at the right hand of Power, and coming with the clouds of heaven.”

Mark 14:61–62

Now, we will disregard Jesus’ response in this study—yes, it is a significant christological proclamation, but that goes beyond our focus. Instead, we shall emphasize Mark’s clever use of syntax so that the high priest ironically proclaims Jesus to be the Christ.

This is contingent on Greek, obviously, for English will not as readily reveal this detail. The Greek reads,

πάλιν ὁ ἀρχιερεὺς ἐπηρώτα αὐτὸν καὶ λέγει αὐτῷ· σὺ εἶ ὁ χριστὸς ὁ υἱὸς τοῦ εὐλογητοῦ;

Again the High Priest asked him and he said to him: “you are the Christ, the Son of the Blessed?”

(my literal translation, retaining the syntax, word-for-word.)

Simply, Greek syntax is not as rigid as English. Words can—more or less—appear anywhere in the sentence and make sense because it is a case-based language.9 This is relatively nonsensical in English since we have largely abandoned cases—the pronominal system has vestiges of this: “I” vs. “me”; “they” vs. “them.”

Syntax is not as helpful in Greek for signaling a question, as Smyth §2641 reads,

Any form of statement (2153) may be used as a direct question. The interrogative meaning may be indicated only by the context, or it may be expressed by placing an emphatic word first or by the use of certain particles (2650, 2651).10

If it were not for the word ἐπηρώτα, “asked,” one could easily translate the verse as a declarative statement rather than a question—though, admittedly, the context would render this unlikely. One could argue that “you” here is the “emphatic word,” but Jesus’s reply to Pilate in a similar circumstance will further help support my claim.

This is an ironic moment in the Gospel of Mark because the High Priest announces that Jesus is the Christ syntactically. Thus, the religious authorities have “acknowledged” who Jesus is, which Jesus, in turn, confirms: “I Am...”

Jesus Pronounced as the King of the Jews by the Romans (15:2)

The ensuing pericope is Peter’s denial, and then Jesus appears before Pilate, a Roman official.11 Here, we have a similar interaction with the Roman prefect as we saw with the High Priest:

And Pilate asked him, “Are you the King of the Jews?” And [Jesus] answered him, “You have said so.”

Mark 15:2

Jesus's reply is the signifier here. Pilate, contextually, did not make a statement; he asked a question. Jesus's retort is a bit nonsensical considering this detail: “You have said so.” No, Pilate asked a question; he did not make a statement. But, this is a second instance of Mark’s cleverness: it is a play on language and syntax:

Καὶ ἐπηρώτησεν αὐτὸν ὁ Πιλᾶτος· σὺ εἶ ὁ βασιλεὺς τῶν Ἰουδαίων; ὁ δὲ ἀποκριθεὶς αὐτῷ λέγει· σὺ λέγεις.

And he asked him [Jesus], Pilate: “You are the King of the Jews?” And he [Jesus], answering, to him said, “You say (so).”

(my literal translation, retaining the syntax, word-for-word.)

This statement is nearly identical to the wording of the High Priest. One would not translate the phrase as a question naturally without the narrator stating that Pilate asked (ἐπηρώτησεν ) Jesus. Jesus’s response, in turn, is similar to the High Priest: You say so. This is another instance of subtle acknowledgement of Jesus’s status that Mark has done through irony and syntax.

Thus, we have two parallel accounts where the Jewish and Roman officials recognize Jesus for who he is. For the Jews, the High Priest announces that he is the Christ. For the Romans, the Prefect announces that he is the King of the Jews.12

Both are done through furtive, subtle linguistic plays in syntax and grammar. Both statements are read as questions because the narrator clues the reader in that the High Priest/Pilate ask Jesus.

These two passages alone do not explicitly show that the Kingdom of God is nearing, but they do help lay the groundwork for preparing the reader that the Christ, Jesus, will soon be mockingly coronated and enthroned in the Gospel.

Since Jesus’ messianic fulfillment is conducted ironically—soon to come—then it makes all the more sense narratively that the High Priest and the Roman authorities would play their own ironic part in the dramatic play.

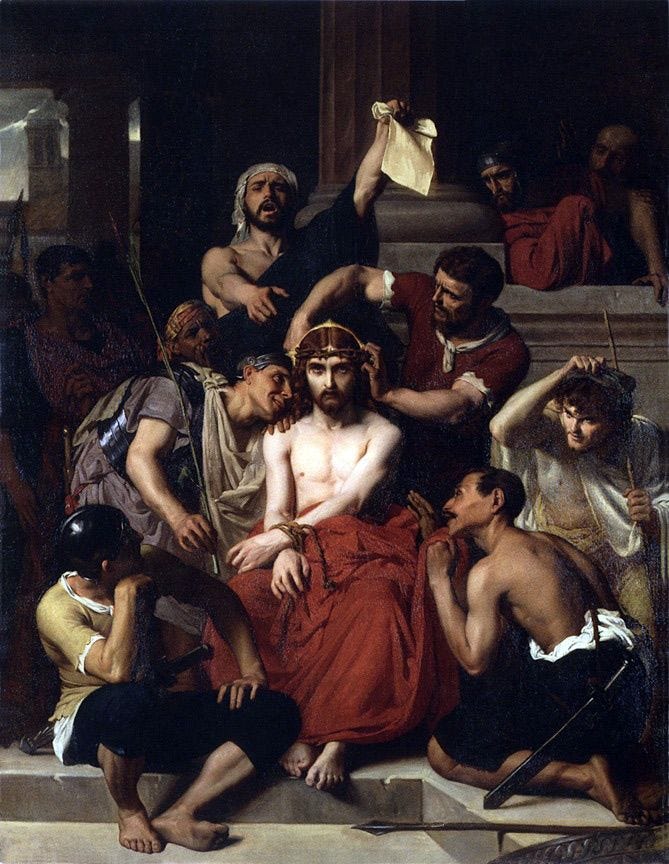

The Mocking Coronation (15:16–20)

In the penultimate pericope, before the climactic crucifixion, we witness the ironic crowning of the Christ before he is seated upon his throne.

In this instance, the entirety of the text is crucial:

|16| And the soldiers led him away inside the palace (that is, the praetorium); and they called together the whole battalion. |17| And they clothed him in a purple cloak, and plaiting a crown of thorns they put it on him. |18| And they began to salute him, “Hail, King of the Jews!” |19| And they struck his head with a reed, and spat upon him, and they knelt down in homage to him. |20| And when they had mocked him, they stripped him of the purple cloak, and put his own clothes on him. And they led him out to crucify him.

Once read through the lenses of mockery and irony, Mark is clearly putting on display that Jesus is recognized as king, akin to the acknowledgment of the High Priest and Prefect—via irony. The soldiers (“in the palace, the praetorium” [τῆς αὐλῆς,13 ὅ ἐστιν πραιτώριον])

Clothed him in a purple cloak—a regal color and garment

Placed a crown (of thorns) upon his head—an obvious designator of royalty

Saluted him and proclaimed, “Hail, the King of the Jews!”—a verbal recognition that Jesus is King, resonating with Pilate’s own “question.”

Kneeled before him (προσεκύνουν, prosekunoun)—veneration of a monarch

More specifically on purple, David and Solomon are associated with purple, and other Near Eastern kings were described as donning the color:

|9| King Solomon made himself a palanquin/from the wood of Lebanon.// |10| He made its posts of silver,/ its back of gold, its seat of purple;

Song of Solomon 3:9–10

And the weight of the golden earrings that he requested was one thousand seven hundred shekels of gold; besides the crescents and the pendants and the purple garments worn by the kings of Mid′ian, and besides the collars that were about the necks of their camels.

Judges 8:26

For an archaeological find that signifies the importance of purple, see this article from Tel Aviv University.

Purple was not reserved just for kings, though, but also the wealthy and the high priest:

And you shall make holy garments for Aaron your brother, for glory and for beauty... They shall receive gold, blue and purple and scarlet stuff, and fine twined linen [for the ephod]...

Exodus 28:2, 5

And so we have appointed you [Jonathan] today to be the high priest of your nation; you are to be called the king’s friend (and he sent him a purple robe and a golden crown) and you are to take our side and keep friendship with us.

1 Mac 10:20

Is there a potential play on Jesus being king and high priest here based upon Psalm 110 (cp. Mark 12:36)? That goes beyond the scope of this analysis, but it is an intriguing thought. All this to say, the color purple is of great significance here, illustrating at minimum royalty. In this mocking display, Mark has ironically shown Jesus to be crowned and pronounced as king.

Although not identical, there are obvious parallels with OT coronations. Take for instance,

|22| ...And they made Solomon the son of David king the second time, and they anointed him as prince for the Lord, and Zadok as priest. |23| Then Solomon sat on the throne of the Lord as king instead of David his father; and he prospered, and all Israel obeyed him.

1 Chron 29:22–23

Then he brought out the king’s son, and put the crown upon him, and gave him the testimony; and they proclaimed him king, and Jehoi′ada and his sons anointed him, and they said, “Long live the king.”

2 Chron 23:11

Though these texts may not specifically be in Mark’s mind, it is striking to note the parallels of crowning and acknowledgment of kingship. Christ’s anointing occurs elsewhere in the narrate (cp. 1:4–8; 14:3–9, though Jesus claims the anointing at Bethany is for burial), but the image of coronation is apparent in the Gospel, even if conducted in mockery.14

The Ironic Enthronement (15:21–32)

After being stripped of his robe, Jesus is led to his throne—the cross—for his crucifixion. The procession makes its way to Golgotha where the enthronement—crucifixion—is to occur. Upon arrival, Mark surreptitiously slips in a key event for revealing the imminent resolution to 9:1 and 14:25,

And they offered him wine mingled with myrrh (ἐσμυρνισμένον οἶνον); but he did not take it.

Mark 15:23

We have examined a few sayings and scenes since our last examination of wine and kingdom, but notice that those present here, just prior to the actual crucifixion, offer Jesus wine, yet he refuses it. The time has not come for the Kingdom of God to be revealed—Christ’s glory is not yet manifest—so it would be inappropriate for him to drink the fruit of the vine at this point in the narrative.

Jesus is then crucified at “the third hour” (v. 25). Christ is now upon his throne, which is clarified in v. 26,

And the inscription of the charge against him read, “The King of the Jews.”

It is now time for James and John’s request to be fulfilled:

And with him they crucified two robbers, one on his right and one on his left.

Mark 15:27

Just as Jesus had responded to James and John:

...but to sit at my right hand or at my left is not mine to grant, but it is for those for whom it has been prepared.

Mark 10:40

The preparations were made, and they have now been carried out. Jesus has been ironically declared as the Christ (cp. 8:29)—by the High Priest—and the King of the Jews—by Pilate and on his inscription. Jesus is now upon his throne in “glory,” with those seated “on his right and... on his left.”

Now, since these foreshadowed events have transpired, the Kingdom of God is here, and it is time for Jesus to partake of his wine.

Of Wine & Kingdom (15:36)

As I have displayed throughout this brief probe, there is a bevy of instances of dramatic irony, subtlety, and mockery throughout the crucifixion narrative. The reader is intended to see this portion of Jesus’s journey as an ironic fulfillment of the messianic claims throughout the Gospel.

Mark has woven together a story that climaxes here. For, there are some of Jesus’s entourage that would see the coming of the Kingdom of God before they tasted death (9:1). It is here at the crucifixion that this comes to fruition; it is here that Jesus will taste the fruit of the vine anew in his Kingdom.

This is on full display just prior to the death of Christ. Just before breathing his last, Jesus cries out Ps 22:1, “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” (v. 34)—the cry of dereliction.15 At this moment, those standing by believe he is calling out to Elijah (v. 35). Then, the wine is delivered to Jesus while on his throne (the cross),

And one ran and, filling a sponge full of [poor wine (ὄξους)], put it on a reed and gave it to him to drink...

Mark 15:36

This is the internal evidence proving the Kingdom of God is present in the narrative, a fulfillment of Jesus’ final words at the Last Supper:

Truly, I say to you,16 I shall not drink again of the fruit of the vine (τοῦ γενήματος τῆς ἀμπέλου) until that day when I drink it new in the kingdom of God.

Mark 14:25

In v. 36, many translations contain the word “vinegar” here, but Mark intends on the reader to read this as the parallel to 15:23, when Jesus is first offered the beverage.17 The narrative fulfillment of Jesus on the cross, situated between two others—one on his left and one on his right—had to come first. Then, and only then, could Jesus “drink... the fruit of the vine” now that it is “that day... in the kingdom of God.”

Should there be any doubt lexically or thematically, this “vinegar” is produced from wine, and the term was also used for cheaper wine.18 To fit with the mocking, ironic narrative, Jesus naturally will consume rotgut rather than a fine cabernet sauvignon. To assume the lexical necessity for Mark to have employed οἰνός—“wine”—is fallacious. Afterall, Mark does not even have Jesus state this in 14:25; rather, he speaks of “fruit of the vine,” which ὄξους, technically, would be.

Mark masterfully knitted these events together to subtly fulfill 9:1;—albeit, this is attained through irony and mockery. Jesus, the coming Christ, the one who is to be enthroned in the Kingdom of God, has his kingly assent accomplished narratively through a way no one expected—as Peter both correctly and incorrectly displayed (8:31–9:1).

Peter’s declaration of Jesus as the Christ and reaction to Jesus’s necessary death encapsulate the irony of the Gospel. When Peter is correct, he is simultaneously wrong because he does not fully understand—a common thread throughout Mark. It is in this moment on the cross that all these subtle, ironic threads are tied into a bow, Mark 9:1 is fulfilled, and Jesus becomes the Christ no one expected him to be.

The final underscore of this message comes in v. 29,

And when the centurion, who stood facing him, saw that he thus breathed his last, he said, “Truly this man was the Son of God!”

This is, once again, an ironic statement, a mocking declaration of who Jesus is—the climax—albeit ironic and mocking—of Gentile inclusion. Another christological and monarchical title, “Son of God,” discloses he is King—a potential appeal to the prologue to the Gospel (1:1).19 But, the centurion is not convinced, nor is he confessing his belief in Jesus as the Christ. Rather, he is mockingly stating the truth, just like his fellow comrades did at the coronation (15:16–20). The scene is complete, dripping with the irony that was poured over the narrative starting with the High Priest. Everyone in the end unknowingly and ironically recognizes who Jesus is, but it is done narratively through mockery.

Conclusion

To doubt the veracity of Mark’s Jesus claiming in 9:1 that some would not taste death until the coming of the Kingdom of God is misguided. On the narrative level, how could Mark have Jesus make such a bold claim and never provide the resolution?

Does he achieve this through an explicit statement or direct reveal? Well, no, but how incredibly Markan it is to tacitly state or subtly imply the fulfillment of a saying through irony and mockery. The reader—even one from the first century—may expect the resurrection to be the revelation of glory, the coming of the Kingdom. But, Mark did not write that. Instead, he has Jesus mocked until the end, an empty tomb, and women fleeing in fear.

Mark focused on Christ crucified; he focused on Christ as King. The coming of the kingdom with power is not what is to be expected; Mark subverts what is power by displaying a crucified Lord. The entire prophetic and literary fulfillment is intended to confuse the reader rather than express these ideas in terms that would be readily understandable—everyone is treated as if they have eyes but do not see, ears but they do not hear (cp. 8:18).

His narrative contains a complex matrix of ideas, themes, and intertextualities that, when read with the proper perspective, becomes clear. The haze is no longer present, and men do not appear as trees, walking (cp. 8:24, another significant cipher for understanding misunderstanding in the Gospel).

In this climactic scene on the cross, the narrative has revealed the coming of the Kingdom of God. This is a clear expression of Mark’s imminent eschatology; the Kingdom of God arrived, according to Mark, at the crucifixion.

The seeds were planted throughout;—Peter’s christological statement and the following passion prediction; the request from James & John and Jesus’s response; the Last Supper and the prediction of wine and Kingdom—the subtle fulfillment of 9:1 and 14:25 ironically blossomed when Jesus, the Christ, the King of the Jews, seated upon his throne and donning his crown, sipped (poor) wine from a sponge between two robbers, one on his left and one on his right.

This was a quick exegetical write-up, but it has been some time since my last post. I thought a hastily written, lightly researched analysis was better than nothing.

If you wish to read more about Mark and the New Testament, would you kindly subscribe?

Now, this might be jarring to read since many will claim that Jesus appears later after the women flee the tomb in Mark 16. That said, I do not believe the shorter or longer ending of Mark are authentic; see Metzger, A Textual Guide to the Greek New Testament. That is not to say the endings are not canonical—they have been codified in the Church. This is a narrative approach to Mark, and I wish to explore what I believe he wrote and intended.

The original ending of Mark (1) is with the women fleeing or (2) has been lost to time. The shorter and longer endings—see the footnotes in your translation on the ms issues—are too convenient, not Markan in the least. Rather, they read as if they are an attempt to harmonize Mark with the later Gospels (Matthew and Luke).

Thematically, Mark makes far more sense with potential despair with the women fleeing in fear. Mark is a subtle writer, and he rarely beats the reader over the head with his intent. One must read closely (and carefully) to extract the subtle theological meaning of the text.

This is not to say that the added endings to Mark are not canonical; that is a conversation for a different time. I am analyzing the text narratively, and I do not believe these are original. If they are—which I’m comfortable with that being reality—then Mark changed his tone, style, and themes rather abruptly. Also, these additions sound too conveniently like harmonizations with the other Gospels.

For an extended walk through how other exegetes in antiquity and modernity have tried to explain away this “hiccup,” see J. Marcus, Mark 8–16, 620.

I consider the Gospels to be catholic works, meaning they are not intended for a specific group or Church. They were composed for all believers.

Review, also M. Boring, Mark, 248ff. He has an extensive excursus on Mark’s Christology, focusing on titles that are employed throughout the Gospel. You may also wish to review John Collins’ The Scepter and the Star: Messianism in Light of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Notice the parallelism in the two accounts. Peter declares, Jesus silences. Jesus declares, Peter silences. The difference being, Peter was incorrect to try and silence Jesus.

One could potentially argue the Transfiguration (9:2–8), too, since Jesus becomes brilliantly radiant. That said, even if this is a true manifestation of Jesus in the narrative, the Crucifixion is the climactic end that truly reveals who Christ is.

Since I will not be discussing Gethsemane, I would at least like to note here the use of “cup” in James and John’s request, the cup here, and the prayer in the Garden when Jesus asks that the “cup” be removed from him. There is a thematic thread here that the cup looks forward to wine, kingdom, and crucifixion.

Many commentators focus on the messianic, eschatological expectation of a later banquet after the conclusion of the Gospel, e.g., R. T. France, The Gospel of Mark; E. Boring, Mark; M. Hooker, The Gospel according to St. Mark.

There are standard arrangements, though, and there is still style in Greek composition. This is only to say that word order does not dictate questions as it does in English.

For more on interrogative statements, see Smyth §2636ff.

Cp. Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 18.3.1. For the differences in titles and archaeological evidence, see this article from Britanica.

There is also a power vacuum that Mark tacitly implies in the Death of John the Baptist—Herod’s birthday bash (6:14–29). I have written about this, too, but it concerns my work on Bread in Mark 6–8.

As such, based on this previous pericope, it is narratively fulfilling that Pilate recognizes Jesus as the new king, which Mark implied at the feeding of the 5,000.

This is a more convoluted discussion of what these terms can signify. A more significant discussion will be left for another time, but the word used for “palace” can signify something pedestrian, like a “farm.” Or, it can mean a royal courtyard or the Temple courtyard (See LSJ and BDAG).

Here, the physical, historical reality of where this occurred is not as important to Mark. These words are meant to spark in the reader’s mind that this is a royal setting. A coronation is about to commence.

See the monarchical language to describe God that is then passed on to Moses in Ezekiel the Tragedian, Exagōgē, 68–82:

|68| I dreamt of a great throne on the top of Mount Sinai,

|69| which was up to the folds of heaven,

|70| upon which an illustrious man sat,

|71| who possessed a crown and a great scepter in his hand,

|72| specifically his left. And with his right, to me

|73| he beckoned. And I stood before his throne;

|74| and he handed over the scepter to me, and upon the great throne

|75| he said to sit. And he gave to me the royal

|76| crown and he departed from the throne.

|77| And I saw the entire round world

|78| and beneath the earth and above the heavens,

|79| and before me, a plethora of stars toward my knees

|80| fell, and I numbered them all.

|81| And they were led (before me) akin to a battalion of men.

|82| Then, I awoke from my slumber and was afraid.

My full translation of the text can be found here.

I will not explicate the significance of the quotation here, but it is another display of subtlety in Mark. Although this appears to be a comment made in despair, the Psalm ends with hope, which the reader is supposed to understand here. Though it may seem dire, this is not where the narrative ends.

Note the formulaic parallelism with 9:1; both start with “Truly, I say to you...”

See LSJ,

A.“(ὀξύς)” poor wine, “vin ordinaire,” Ar.Ach.35 ; “κοτύλας τέτταρας ὄξους Δεκελικοῦ” Alex.285, cf. X.An.2.3.14, POxy.1275.20 (iii A. D.) ; cf. “ὀξίνης” 1.

2. vinegar made therefrom, IG12.334.4, A.Ag.322, Hp.Acut.61, Gal.11.413, etc.; “ὑπώμνυτο ὁ μὲν οἶνος ὄ. αὑτὸν εἶναι γνήσιον, τὸ δ᾽ ὄ. οἶνον αὑτό” Eub.65; “σφόδρ᾽ ἐστὶν... ὁ βίος οἴνῳ προσφερής: ὅταν ᾖ τὸ λοιπὸν μικρόν, ὄ. γίγνεται” Antiph.240 ; ἐς τὰς ῥῖνας ὄ. ἐγχέων, as a mode of torture, Ar.Ra.620.

See BDAG, “sour wine, wine vinegar, it relieved thirst more effectively than water and, being cheaper than regular wine, it was a favorite beverage of the lower ranks of society and of those in moderate circumstances...”

Though, “Son of God” has text critical issues and may not be original to the Gospel. Although that may be the case, the title certainly has thematic significance in Mark, and it certainly would be fitting to be present there.