Proteus Emerges in the Early Church (Part I)

An Historiographical and Stylistic Examination of Three Pauline Speeches in Acts | Introduction and Modern Historiography

Acts is the earliest extant history of the Early Church, but is the chronicling a reliable text? This is a difficult question to answer because the transmission of information, specifically the recording of events, is a difficult task. As for antiquity in particular, there were no recording devices, not everyone was capable of writing, supplies needed for record keeping were expensive and in shorter supply, and the memory skills of ancients were as unreliable as eyewitnesses are today.

The limitations of the first century do not impact modern historiography, but the difficulties of today revolve around theory. Although the practice of tracking history philosophically is a concern now, that does not mean that the ancients were not aware of varying methodologies, nor were they unaware of how to compose a reliable history.

This multi-part series tracks both modern and ancient methods of historiography. Based upon Wayne Meeks’s discussion of Paul as the Christian Proteus, we will follow his lead and read Luke’s presentation of Paul’s involvement in the Early Church through this lens.

Luke1 was a careful historian, which is exemplified by his ability to adapt the narrative and speeches in his Acts of the Apostles, and this may potentially reveal some positive reliability to the account. Although it is debated how seriously we can assess his presentation of the Church’s early narrative, it is at least plausible that the author’s work falls in line with other history compilers from antiquity.

This first part of the analysis will entail a brief survey of modern historiographical approaches and religious theory. This will serve as a foundation for approaching the history and speeches in Acts.

Our second exploration will be concerning ancient historiography, but I will not limit this discussion to just historical sources. There can be historical nuggets recorded in fictional works, which can be helpful in piecing together what happened in the past. This will then lead to an exploration of ancient speech recording techniques.

The third and final article will explore how Luke ingeniously crafted Paul’s speeches to reflect the sentiments expressed in 1 Cor 9:19–23—“...I have become all things to all men, that I might by all means save some” (RSV). Regardless of the precise historical veracity of the accounts, Luke was exceedingly conscientious of how he framed Paul's missionary work and the birth of the Church.

The final discussion concludes with an exegetical exploration of three speeches in Acts: Paul before Jews (13:13–52), Gentiles (17:16–34), and a community he established (20:17–38). I conclude that Luke likely knew many of the epistles and traditions concerning Paul's rhetorical adaptability, which he portrayed through a profusion of speeches placed in Paul's mouth. This study, ultimately, is an exploration of historiographical methodology and the reliability of Luke’s account. The final analysis of three Pauline speeches will serve as an example of how history was recorded in antiquity, which embraced literary features, as well as explore the importance of an author’s role in constructing and interpreting these events.

Introduction

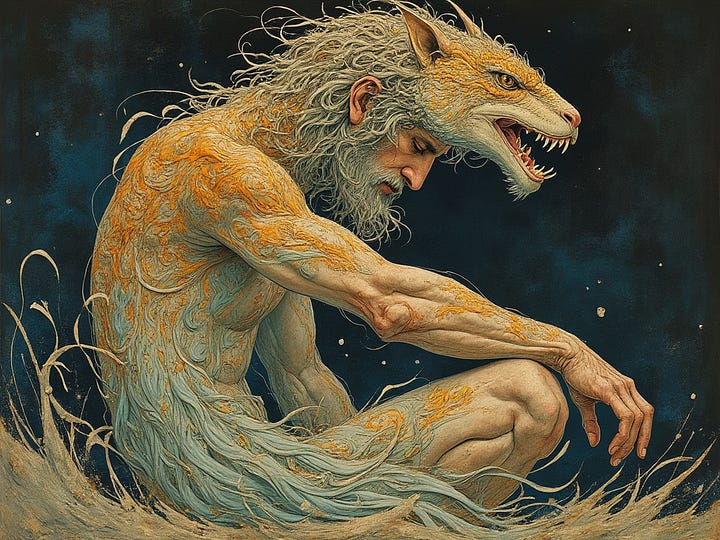

Wayne Meeks contended in his chapter, “The Christian Proteus,” that Paul resembles the sea-god from Homer’s Odyssey since many scholars throughout history have attempted to seize Paul and wrestle with the meaning of his disparate epistles:

...the history of the reception of Paul’s letters and of his story impresses upon us both the malleability of their meaning and the unending variety of ways that readers have injected their own identities into the process of interpretation.2

Meeks’ emphasis in his paper is concerned with how interpreters have struggled to latch onto Paul’s thought and distill a comprehensive and comprehensible systematic theology from his one-sided conversations—his letters. But, I wish to take this concept of Proteus and capitalize on his adaptability to shape-shift to frighten those who wished to grip him and apply this characteristic to the Paul described in Acts.

Concerning the Sea-God Proteus

Homer described Menelaus’s encounter with Proteus, “the ever-truthful Old Man of the Sea,” as follows,3

We with a cry sprang up and rushed upon him, locking him

in our arms, but the Old Man did not forget the subtlety

of his arts. First he turned into a great bearded lion,

and then to a serpent, then to a leopard, then to a great boar,

and he turned into fluid water, to a tree with towering branches,

but we held stiffly on to him with enduring spirit. (Homer, Ody. 454–459)4

The sea-god Proteus was a shapeshifter who was able to morph into whatever form he thought might frighten his aggressor. Upon seeing Proteus transform into a beast or terrifying creature, the instigator would relinquish his grasp, rendering the Old Man free. If one were able to hold fast, the prophetic god would disclose any information concerning the future the interrogator wished to know. This mythological figure was adopted by a number of authors in order to describe a character whose proclivity was to adapt for personal benefit.5

The hero of Homer’s epic poem, the πολύτροπος (polutropos), “much-turned, i.e., much-traveled,” Odysseus, was often likened to Proteus, for he was considered a flatterer, one who would say whatever was necessary to attain his desires.6

This mentality translated into various forms of literature other than poetry and narrative.7 For instance, Athenaeus stated in Sophists at Dinner (LCL 224.160–161) that “the flatterer, in one and the same person, is the very image of Proteus. At any rate, he assumes every kind of shape and of speech as well, so varied are his tones.” The reader can see why Meeks likened Paul to such an adaptable trope, for “[Paul] veered from one side to another not only in order to approach different audiences, but in order to resist different points of view that he thought inimical to the peace and unity of the faithful.”8

Concerning the Evangelist-Historiographer Luke

A vast amount of the biographical information about Paul at our disposal derives not from his epistles, but rather from an anonymously written composition known as the Acts of the Apostles.9 Although the work contains no authorial recognition, the Church espouses that Luke was one of the συνεργοί (sunergoi)—“co-worker”—mentioned in Philemon (v. 24), the ἰατρός (hiatros)—“doctor”—of Colossians (4:14), and the one with Paul in 2 Timothy (4:11).10

Although debated within scholarship, the Church early on taught that the book was an historically reliable account of the nascent Church, written akin to other histories of antiquity. As Eusebius asserted,

Luke was by race an Antiochian and by profession a physician. He long had been a companion of Paul and had more than a casual acquaintance with the rest of the apostles. He left for us, in two inspired books, examples of the art of healing souls that he obtained from them. These books are, namely, the Gospel... the Acts of the Apostles, which he composed not from hearsay evidence but as demonstrated before his own eyes. They say that Paul was actually accustomed to quote the Gospel according to St. Luke. When writing about some Gospel as his own, he used to say, “According to my Gospel (Rom 2:16; 16:25; 2 Tim 2:8).” (Hist. eccl. 3.4)11

The debate concerning the historical veracity of Acts wages on because there is no consensus on Luke’s12 historiographical methodology. Even though the Early Church believed that the account was genuine, skeptics assert that the discrepancies that lie between the epistles and the Dopplewerk—German, “double-work,” a common name for Luke-Acts—are irreconcilable.13

As is the trend in every realm of scholarship, there is a range of beliefs concerning how one ought to approach the historical accuracy of Luke-Acts.14

Purpose of Analyzing the History & Speeches in Acts

This series seeks to contribute to the discussion concerning some of these historical tensions and categorical contentions through an historiographical explication of the speeches found in Acts, focusing on their stylistic presentation. I hold that Luke was quite familiar with the rhetorical techniques expressed in Paul’s letters and, potentially, with Paul’s oral capacities—it is impossible to know how much the author actually knew or possibly experienced. Luke presented Paul as the Proteus of the Church derived from such claims as 1 Cor 9:19–23 (BroSV),

|19| For although I am free from all things, I enslaved myself to everything in order that I might gain more; |20| and I became for the Jews as a Jew so that I might gain the Jews; for those under the law as under the law—though I am not myself under the law—so that I might gain those under the law; |21| for the lawless as lawless—though I am not lawless from God but (I am) in accordance with the Law of Christ—so that I might gain the lawless; |22| I became weak for those who are weak, so that I might gain the weak; I have become all things for everyone in order that in every way I might save some. |23| I do all things on account of the Good News so that I might become a partner with it.

Through this expression, the Christian Proteus declared his rhetorical methodology, that he will adapt for the sake of the promulgation of the Gospel.

Luke, in turn, followed in the methodological footsteps of Thucydides for crafting recorded speeches:

Therefore the speeches are given in the language in which, as it seemed to me, the several speakers would express, on the subjects under consideration, the sentiments most befitting the occasion, though at the same time I have adhered as closely as possible to the general sense of what was actually said (1.22.1 LCL).

Luke desired to represent the Paul that he knew from the epistles, and he did so when constructing the speeches he placed on Paul’s tongue. I will disclose through an exegetical analysis of three Pauline speeches in Acts that Luke adhered to many historiographical norms that were present during the first century.

Religious Theory, Modern Historiography, and Luke-Acts

The art of history writing is a convoluted venture because there are many factors that weigh upon the author who seeks to re-present the past.15 Prior to assessing Luke’s historical compilation, let us explore briefly a paucity of pertinent fields of scholarship that will aid us in our assessment. The first concerns religious theory, which will lay the foundations for comprehending the Jewish and Greco-Roman components of Luke’s perspective—the melding and mixing of two cultural milieus. The second will pertain to modern sentiments of historical theory. This will serve as a springboard for later discussions on ancient conceptualizations of history writing and Luke-Acts.

Crossing & Dwelling: Luke the Border-Crosser

The focus of this section will revolve around Thomas Tweed’s religious theory contained in Crossing and Dwelling: A Theory of Religion wherein he analyzes a proper way of defining religion so that it might be more applicable today. Tweed states, “I was looking for a theory of religion that made sense of the religious life of transnational migrants and addressed three themes—movement, relation, and position…” He claims, “Religions are confluences of organic-cultural flows that intensify joy and confront suffering by drawing on human and suprahuman forces to make homes and cross boundaries.”16

Tweed emphasizes the interaction and movement of people and their relations in order to better understand the cultural factors that impact religious movements. Religions create homes which distinguish those within the community and those outside; it essentially orients a person in their current circumstances and environment. But, this aspect of “dwelling” is not the only consideration when discussing religious movements. “Crossing” is the second component of Tweed’s definition. This entails the idea that each person must cross boundaries and interact with the Other.17 His theory

...is, above all, about movement and relation, and it is an attempt to correct theories that have presupposed stasis and minimized interdependence... Religions designate where we are from, identify whom we are with, and prescribe how we move across.18

With this brief understanding of Tweed’s thesis, let us now explore its relation to Luke and how he can be perceived as a border-crosser. As Tweed mentioned above, three themes are imperative for understanding religion: movement, relation, and position. Luke encapsulates this in his portrayal of Paul.

The reader should note that as Luke developed his narrative-history, his style reflected his desire to appeal both to Jew and Gentile alike. This can be witnessed in Luke’s own writing style and how he presented leading characters. Therefore, as a border-crosser, it is significant to keep in mind that when speaking of “Jewish” or “Hellenistic” influences, Luke is not, presumably, entirely conscious of these distinctions.19

Luke attempted to construct a communal identity that would bring unity to the members of a congregation that contained both Jews and Greeks.20 As such, Tweed asserts,

The religious not only need to be propelled to imagined pasts and desired futures, they need to be called back, summoned to the present. Narratives, rituals, codes, and artifacts do that.21

Through his narrative-history, Luke is able to do precisely this by constructing a myth. As Hesiod was for the Greeks with his Theogony, so also was Luke with his—what I call—Ecclesiogony, “Birth of the Church.”

This is a term I created in order to encapsulate the nuances displayed in this discussion. The word captures the Hellenistic flavor of Luke's work by bringing to mind Hesiod’s Theogony, “Birth of the Gods.” This myth was important to the Greeks; it was a foundational epic poem for their culture and beliefs. Luke was able to have a similar effect on his growing community through a telling of the Church’s inception. The critical aspect for many of Paul’s writings are centered around concord and unity, which is embodied in Luke’s depiction of the Early Church.

By formulating this two-volume work, Luke has created a Christian myth for the ecclesia—the Church. With respect to myth, David Horrell claims,

The term “myth,” of course, conjures up a range of allusions, not least the popular connotation of a myth as essentially a lie. In the study of religion, however, the term myth has been more positively used to refer to a means by which (a) “truth” is conveyed.22

As Gerd Theissen also asserted, “Myths explain in narrative form what fundamentally determines the world and life.”23 Through formulating his Ecclesiogony, Luke sought to promote a unified church.

Modern Perspectives on Historiography

Marc Trachtenberg commented on a developing predicament for modern approaches to and assessments of history, stating, “Increasingly the old ideal of historical objectivity is dismissed out of hand. The very notion of ‘historical truth’ is now often considered hopelessly naive.”24 It is no wonder that such skepticism has permeated the academy with respect to ancient records, for there is such a lack of resources at our disposal that are able to definitively substantiate their veracity. One need only glance at a paucity of news reports that discuss a particular incident to perceive that disparate assessments of current events exist in our modern context; so also it must have been in antiquity.

What Is History?—Establishing the Art of Historiography

Commenting on postmodern skepticism, Gregory Laughery states, “writing history has more to do with inventing meaning than with finding facts. Any pursuit of the truth of historical occurrence in the past becomes highly dubious.”25 To be sure, the standards of modern historiography differ drastically from those of antiquity.

To find the truth that undergirds these texts is a difficult task because we are so far removed culturally and literarily. In turn, truth is nebulous when pertaining to a recounting of past events due to the elusive nature of writing history. As will be argued, interpretation is what drives history writing, and it is what provides true meaning and significance to the past. Were it just about a simple recording of who, what, when, and where, the task would be rather simplistic; the why generates a profound number of issues.

Writing on the life and theology of Paul, Udo Schnelle offers an intriguing perspective concerning how the art of history writing is executed and what implications it has on the completed work. He states,

As the present passes into the past, it irrevocably loses its character as reality. For this reason alone it is not possible to recall the past without rupture into the present. The temporal interval signifies a fading away in every regard; it disallows historical knowledge in the sense of a comprehensive restoration of what once happened. All one can do is declare in the present one’s own interpretation of the past.26

Schnelle argues that it is from our present perspective that any understanding can be ascertained from past events. It is through this lens that we are able to gaze back into the past and perceive a hazy picture of what once was or, better, what might have been. It is, therefore, through this present interpretation that meaning is gained.

The past loses its “true” character and reality due to the interpretation the writer imposes onto the account. The person arranging this material is thus extrapolating an interpretation, for the historian combines sources thereby infusing significance into the cohesive whole they have amalgamated.

Jens Schröter argues,

It is… this interpretation of the remains and sources as well as their placement in a context sketched by the historian that gives the meaning of the past meaning for the present. Independent of this interpretation there is no history, but only dead material.27

This is the case since,

The fundamental principle is that history originates only after the event on which it is based has been discerned as relevant for the present, so that necessarily history cannot have the same claim to reality as the events themselves on which it is based.28

The one constructing the account has a great amount of sway on the “reality” of what happened since they are the one orchestrating the story. As Schnelle contends,

History is not reconstructed but unavoidably and necessarily constructed… Historical interpretation means the creation of a coherent framework of meaning; facts only become what they are for us by the creation of such a historical narrative framework.29

Inadvertently, when the historian decides what stories he or she is going to recount and where the narrative is going to begin and end, they have in essence constructed a framework for what they are about to describe.30 The historian judges what is important and how the events relate to one another, thereby imbuing them with meaning.31 In turn, a narrative has been created based upon the whims of the author; the events that support his or her interpretation of the story are included, whereas others deemed superfluous are abandoned.

It would be an impossible endeavor for the historian to recount every event and detail pertaining to their history. Thus, the historian must decide what is most relevant to what they are attempting to claim happened. It is an interpretive move when one chooses what should be incorporated into the narrative that will later be called “history.”

This is problematic for assessing ancient historians because at times, we have at our disposal only one source for a particular time period in a specific region. At that point, we are at the mercy of that writer and the “truth” they have provided. Inevitably, that composer did not retell everything, and much is presupposed with respect to cultural norms, practices, and language. Apart from these presuppositions, we commonly neglect the unreliability of human memory, and this inadequacy of the human mind further contributes to modern skepticism and doubt concerning ancient accounts.32

A Negative View of Historiography

Hayden White impacted the perception of modern historiography on account of his skeptical approach to the methodology of recording history. Historical accounts, in his view, are as much, if not more, literary than they are historical. White asserts quite strongly that

...there has been a reluctance to consider historical narratives as what they most manifestly are: verbal fictions, the contents of which are so much invented as found and the forms of which have more in common with their counterparts in literature than they have with those in the sciences.33

By drawing this comparison, history can be paired with literature, and so he insinuates that much of historical retellings categorically falls into fiction.34 He believes that the interpretive flavor added to every historical account results in a fictional narrative that is based upon “facts,” thus rendering the work as literature.

White downplays the scientific nature of historiography stating,

It is sometimes said that the aim of the historian is to explain the past by “finding,” “identifying,” or “uncovering,” the “stories” that lie buried in chronicles; and that the difference between “history” and “fiction” resides in the fact that the historian “finds” his stories, whereas the fiction writer “invents” his. This conception of the historian’s task, however, obscures the extent to which “invention” also plays a part in the historian’s operations.35

White is correct to establish that invention is a large component of every historical writing. White appears to push his point a bit too far, though, arguing that “facts” are constructed rather than discovered.36 Since the historian seemingly has the “authority” to set the boundaries of the text—establishing the beginning, middle, and end of the account, which events will be included, etc.—they play quite an inventive role in the formulation of history. Our perception and view of the past is molded and constructed by those who chronicle these accounts.

As the famous truism goes, “History is written by the victors,” it is apparent that many are at least partially conscious of this creative/inventive component of history.

Conclusion

Although I contended previously that Luke is a reliable historian, this should be met with some reluctance because we must establish what is meant by this statement. The impetus for writing is what drives the pen of the author, and it is in this theologically driven narrative-history that truth can be found.

The narrative and the theological underpinnings of the tale pushed Luke to create the Christian Proteus in his Ecclessiogany. Like in the Gospels and other New Testament texts, it is the message that is critical to grasp, not the particulars. Will there be errors, half-truths, historical stretches, and generated speeches contained within? I believe so.

This goes beyond the scope of the conclusion, but Jesus’s conversation with Nicodemus in John 3 is a prime example of a generated story to fit the theological or thematic push of the author. In this particular instance, the conversation only works in Greek, which is unlikely to have actually occurred between the two figures. Regardless, it is the message that matters most to John, not the historical veracity. It must be remembered that the works in the New Testament are theological in nature; they are not strictly historical accounts wishing to present “dead material” to be absorbed.

The historical data included in Acts is the vehicle by which a theological message might be conveyed. And so, Luke began his narrative with the Ascension and ended prior to Paul’s death for a reason. This will become more evident after we discuss ancient historiography and examine the three Pauline speeches that I have chosen.

Keep in mind, history is by nature a narrative. In the following two articles I will establish this more definitively. Next, I will establish the basics of ancient historiography with a comparison of Luke’s introduction to other sources to show that his work falls in line with others in antiquity. The final piece will evaluate the three Pauline speeches to further show the historical and literary nature of the Acts of the Apostles.

If you wish to continue reading about Luke, Paul, Acts, and the historiography of the Early Church, would you kindly subscribe?

There is no signature or claim in the text itself that “Luke” the evangelist wrote this history of the Early Church. For convenience, we will follow Church tradition and continue calling the author “Luke,” but it is only based on tradition that the Gospel and Acts are believed to be written by Luke. There is some dissent that the two pieces were written by the same person, but I side with the majority view that there is one author.

Wayne Meeks, “The Christian Proteus” in The Writings of St. Paul (W. W. Norton, 2007).

Proteus is described similarly in Virgil’s Georgica, book 4.

Translation from R. Lattimore. The Odyssey of Homer (Harper, 1967).

For example, Shakespeare (Henry VI, Part Three, Act III, Scene ii) uses Proteus as a parallel:

I can add colors to the chameleon,

Change shapes with Proteus for advantages,

And set the murderous Machiavel to school.

Can I do this, and cannot get a crown?

Tut, were it farther off, I'll pluck it down.

For a discussion on the reception history of Odysseus, consult W. B. Stanford. Ulysses Theme (Barnes and Noble, 1968).

This phenomenon occurred in antiquity as well as in later periods, such as the Renaissance. For more on the use of Proteus in post-antiquity literature, see A. Giamatti, Exile and Change in Renaissance Literature (Yale, 1984).

Meeks, “Proteus,” 691. Though, I do want to make clear that I do not hold Paul to be a flatterer in the pejorative sense that Athenaeus presents. Paul was similar to Proteus since he was able to adjust what he was saying to fit the needs of those whom he was addressing.

This can be problematic since Acts supplies information concerning Paul that is not extant in any of his epistles. For a balanced study of the discrepancies between Paul and Acts, see M. Gorman, Apostle of the Crucified Lord (Eerdmans, 2004).

See Jerome’s De Viris Illustribus, chapter 7. He claims that the Luke of the epistles is the Antiochan who composed Acts. Jerome provides extra-biblical biographical quips concerning Luke's participation in the history of the incipient Church.

Quotation from T. Oden. “Luke,” in Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture vol. 3. (InterVarsity, 2003), 2. Also, see St. Ambrose, Exp. Luc., 1.4, 7.

The authorship of Luke-Acts will not be a point of discussion in this paper. I have chosen to use “Luke” as the name of the author for convenience; the contention matters little for this present analysis. As Michel Foucault, “What is an Author?” in The Foucault Reader (Pantheon, 1984), 120 wrote, “What difference does it make who is speaking?”

Skepticism arose from F. C. Baur and the Tübingen school. See Ernst Haenchen, The Acts of the Apostles (Blackwell, 1971) and Hans Conzelmann, History of Primitive Christianity (Abingdon, 1973).

For example, there are numerous positive assessments of Luke's history; consult Martin Hengel, Acts and the History of Earliest Christianity (SCM, 1979) and F. F. Bruce, The Book of the Acts (Eerdmans, 1988). For a balanced approach to Acts and historiography, see Jens Schröter, From Jesus to the New Testament (Baylor, 2013).

In the words of Emmanuel Levinas, Totality and Infinity (Duquesne, 1969), 65, “For to know objectively is to know the historical, the fact, the already happened, the already passed by. The historical is not defined by the past; both the historical and the past are defined as themes of which one can speak. They are thematized precisely because they no longer speak. The historical is forever absent from its very presence. This means that it disappears behind its manifestations; its apparition is always superficial and equivocal; its origin, its principle, always elsewhere.”

Thomas Tweed, Crossing and Dwelling (Harvard, 2006), 5, 54.

“To recognize the Other is therefore to come to him across the world of possessed things, but at the same time to establish, by gift, community and universality. Language is universal because it is the very passage from individual to general, because it offers things which are mine to the other. To speak is to make the world common, to create commonplaces. Language does not refer to the generality of concepts but lays the foundations for a possession in common” (Levinas, Totality and Infinity, 76). The language that Luke used in his history is the means by which he was able to foster a form of solidarity in the community. Paul was portrayed as a Proteus who was able to shift his words to the needs of his audiences.

Tweed, Crossing and Dwelling, 77, 79.

Luke lived in a Greco-Roman, Jewish milieu, and he was most likely not aware whence certain aspects of his thought and writing derived. This is not to assume that he did not capitalize on certain aspects when they were appropriate or beneficial.

I am not speaking exclusively of Luke’s specific community. Luke’s broader Church consisted of both Jews and Greeks, and unification was an issue. This is seen in 1 Corinthians concerning the weak and the strong as well as the Jerusalem Council.

Tweed, Crossing and Dwelling, 162.

David Horrell, Solidarity and Difference (T&T Clark, 2005), 85. C.S. Lewis, “Myth Became Fact,” in God in the Dock (Eerdmans, 2001) asserted, “The heart of Christianity is a myth which is also a fact... To be truly Christian we must both assent to the historical fact and also receive the myth (fact though it has become) with the same imaginative embrace which we accord to all myths. The one is hardly more necessary than the other.” Finally, J. R. R. Tolkien, “On Fairy-stories,” in Tree and Leaf (Unwin, 1970), 63 expresses similar sentiments: “this story is supreme; and it is true. Art has been verified. God is the Lord, of angels, and of men—and of elves. Legend and History have met and fused.”

G. Theissen, A Theory of Primitive Christian Religion (SCM, 1999), 3.

M. Trachtenber, “The Past Under Siege,” in Reconstructing History (Routledge, 1999), 9.

G. Laughery. “Ricoeur on History, Fiction, and Biblical Hermeneutics,” in “Behind” the Text (Routledge, 1997), 340.

U. Schnelle, Apostle Paul (Baker, 2005), 27.

Schröter, From Jesus to the New Testament, 39.

Schnelle, Apostle Paul, 31.

Schnelle, Apostle Paul, 28, 30.

This is especially evident in the Gospel narratives. Each evangelist begins his story of Jesus at different parts of the ministry and recounts them in different ways. They have infused the “truth” with interpretation.

More skeptical commentators on Acts would perceive this as problematic. For example, the Jew-Gentile conflict was a major concern for scholars like Haenchen and Conzelmann. Hans Conzelmann, History of Primitive Christianity (Abingdon, 1973), 15–16 stated absolutely, “Where the book of Acts and Galatians diverge from each other, Galatians always deserves to be preferred. Luke apparently did not possess a coherent source on the council but attempted to form a picture from scattered reports.” This fails to place the two accounts in conversation. Paul’s letter is one perspective, and Luke’s another. There must be some veracity lingering beneath both, so to propose one should be discounted entirely based on an apparent lack of sources is too harsh. The two authors had quite different reasons for writing, and this must be taken into account before passing judgment on one as absolutely contrived.

Memory is always a factor of uncertainty. Christopher Noland reveals this notion in his film, Memento, through Leonard Shelby’s remark that “Memory can change the shape of a room; it can change the color of a car. And memories can be distorted. They're just an interpretation, they're not a record, and they're irrelevant if you have the facts.” Noland cleverly manipulates the meaning of “fact,” for Leonard Shelby is perpetually re-inventing what the “truth” is. The twist in the film reveals that the “facts” are more easily invented than gathered, especially when it is for personal benefit.

H. White, “Historical Text as a Literary Artifact,” in History and Theory (Blackwell, 1998), 16.

This trend is seen in the assessment of Acts. Haenchen, Acts, 83 executed his critical approach to Acts through form- and redaction-criticism attempting to reveal the sources Luke may have possessed. He arrived at the conclusion that quite frequently when Luke appears to have no source in hand, “He seeks to supply this deficiency by drawing conclusions from the information available and adding complementary details.”

H. White. Metahistory (Johns Hopkins, 1973).

See H. White, “Afterword,” in Beyond the Cultural Turn (University of California, 1999).