Textual Criticism, What it is and Why It Matters (I)

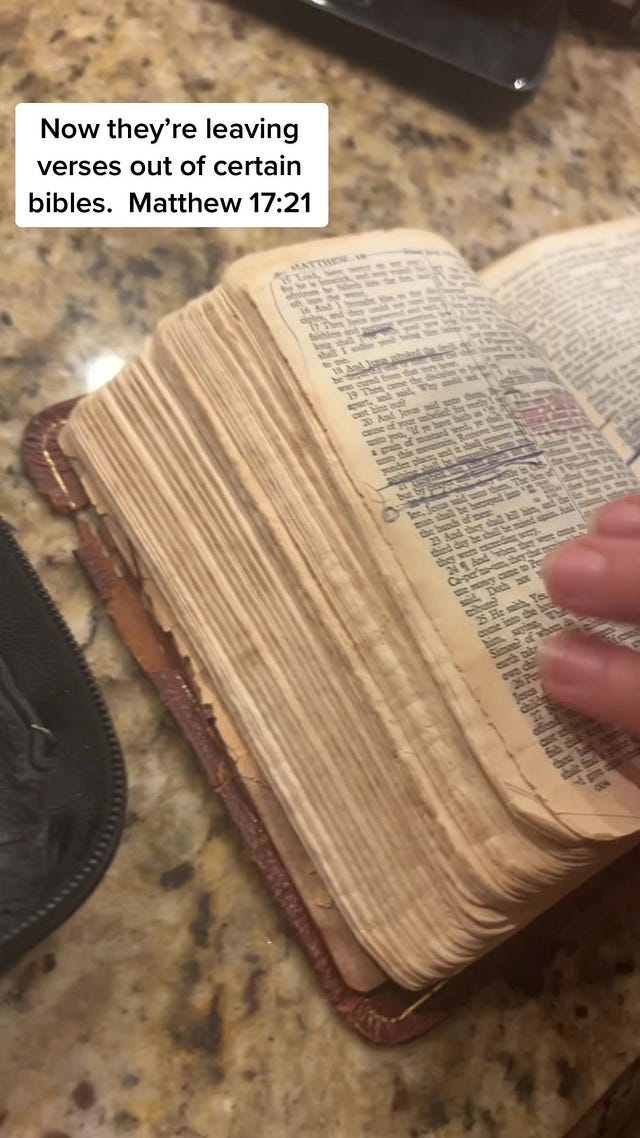

An example of misunderstanding and ignorance from TikTok

Introduction

Not too long ago, I happened upon a video claiming “they” are changing your Bibles.1 Who are “they” exactly? A shadow cabal hell-bent on changing the biblical text, perhaps? This is intentionally left ambiguous because these individuals seemingly have no real culprit; it is purely conspiratorial.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

My initial viewing left me a bit speechless because I thought there is no way someone could be this ignorant and oblivious—even for TikTok. Then, I made a grave mistake; I began reading the comments. The scales fell off my eyes, and I realized people really do not understand (1) textual criticism, (2) manuscripts, and (3) the Hebrew and Greek texts that are used for modern translations.2

So, what is textual criticism—or “lower” criticism? It is an attempt to reconstruct an original document that is no longer extant. Because there are no surviving original manuscripts (mss) of the New Testament,—all are copies—we have to assemble from our textual witnesses what the text might have been. Furthermore, the art and science of textual criticism is an assessment of those copies, comparing and contrasting them, weighing the evidence, analyzing the variants, and making a logical decision on what the original text most probably contained.

This post has grown to be larger than I had initially intended, so I plan to split it up into three entries: (1) an introduction and problems with the video; (2) manuscript types and textual families; and (3) the methodology of textual criticism and a practical example—why Matt 17:21 is inauthentic.

Overall, I will provide the basics of textual criticism so that you may understand what the process is and why it is important. You will, at the very least, be able to recognize a faulty argument based on conspiracy, prejudice, and ignorance.

What Is Problematic with the Video?

Even if you have never heard of textual criticism—and let’s just assume you had no inkling that no original ms of the New Testament survived—the presentation in the video should still seem suspicious. First, their “knock-out” punch is based solely on the King James Version (KJV), in that it contains the verse, so it must be original. Secondly, their argument for the verse’s deletion is speculative and conspiratorial, and the claim is left unsubstantiated.

The King James Version and Its Primary Issue

The King James Version (KJV) is beloved by many, and it has certainly left its mark on the English language. In the Western canon, the KJV will forever be a landmark work that deserves respect. That being said, it also has a rather unfortunate quality that compromises its reliability.

The translation is based on some sketchy textual criticism work in a document later dubbed the Textus Receptus (1633),—the “received text”—which was first produced by Erasmus, a 15/16c. humanist. The Textus Receptus is a Greek New Testament that was meant to clear up some uncertainty about what the original Greek actually contained, and it is the basis for numerous translations, e.g., Luther’s German translation (1522), Tyndale’s English translation (1525), KJV/NKJV, and the Geneva Bible.

Erasmus had serious concerns with what had previously been used for translations, writing,

...often through the translator's clumsiness or inattention the Greek has been wrongly rendered; often the true and genuine reading has been corrupted by ignorant scribes, which we see happen every day, or altered by scribes who are half-taught and half-asleep. (Epistle 337)

The irony of this statement is almost comical since the Textus Receptus is based on only a few mss, and they are late (the Medieval period, 12 & 13c.) with their own set of errors—not to mention Erasmus’s first edition was rife with typographical errors. The comedic irony is heightened by the fact his copy of Revelation was missing the last page, so he translated the Vulgate (Latin translation of the Bible)3 back into Greek for the final 6 verses. It may come to you as a shock, but what he rendered was not entirely accurate and is text critically rather worthless.4

Moreover, most scholars consider the work to be dodgy because the ms tradition behind the text is exceedingly narrow (Byzantine tradition).5 Today, our translations are based on a Greek eclectic text—a reconstructed document from multiple witnesses—that is far more reliable because we consult and analyze more data (mss) and have better evaluative techniques.6

The Problems with Conspiracy

The second glaring issue is their conspiratorial attitude towards modern translations. It is critical to note that the individuals in this video surreptitiously and intentionally ignore a niggling footnote for Matt 17:21. The reason for this omission is obvious: it utterly undermines the entire claim. Take a look at what the publishers have printed in a number of translations,

Now, most Bible readers are at the mercy of the translator/textual critic for assessing how decisions like this are made since there is no in-depth discussion in the front matter of their Bible on the process.7 How then are you, the reader, supposed to digest this information? In short, it is nearly impossible for the laity to assess the data; as Raymond Brown notes, “...textual criticism can be a very difficult pursuit; and most beginners in NT study find it uninteresting or too difficult since it involves a technical knowledge of Greek.”8 That said, even if you are ignorant of Greek, the basic argument for Matt 17:21’s exclusion is fairly easy to follow, and it can serve as a starting point for discussing textual criticism.

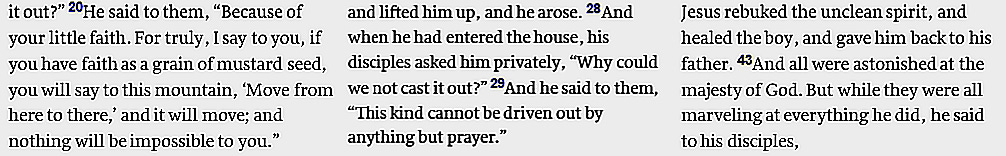

If we take a look at the Synoptic Gospels—Matthew, Mark, and Luke—we will see they all contain this pericope, with some variations (Matt 17:14–21//Mark 9:14–29//Luke 9:37–43). The narrative comes right after the Transfiguration, and it concerns a boy possessed by a demon/unclean spirit. In each account, the disciples are unable to drive out the spirit, to which Jesus responds with consternation, but only Mark contains the closing phrase, “This kind cannot be driven out by anything but prayer [and fasting].” Here is the final verse of the pericope in each Gospel:

Notice that Mark has the verse, but Matthew and Luke do not in the RSV.9 We will discuss manuscript families and other steps in determining originality later, but there is an easy explanation for how the addition could have arisen in Matthew: scribal error.

But first, it is critical to remember that the synoptic Gospels are quite similar. Yes, they each have distinct qualities, exclusive narratives, and unique sayings of Jesus, but if I were to ask you which Gospel has the Sermon on the Mount, which has Jesus sticking his fingers into a deaf man’s ears, and which has the story of Jesus’s birth in a manger, could you answer with certainty? And, to drive the point home, if I were to ask you to identify a saying of Jesus that is not identical in all the Gospels, e.g., Jesus’s dying words—“My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?”; “It is finished”; “Father, into thy hands I commit my spirit!”—would you be able to reply with confidence in which Gospel each phrase is found? If you can, that’s awesome; you are the exception, not the rule. For most people, it is exceedingly easy to mix up the Gospel accounts.

So, bearing that in mind for Matt 17:21, if the scribe making the copy is aware of Mark's version, yet is hazy on the particulars of Matthew’s, and when copying Matthew, he notices its absence, he falsely believes the previous copyist made a mistake by omitting the verse. In his mind, by adding v. 21, he has “restored” what should be present, when the First Gospel never had it originally. It is a conflation of what he knew should be in Mark with Matthew; it's technically an error.

There is more to the process, as we will discuss (entry #3), and there is no certainty that this is exactly what happened. But, when scholars determined this was a later scribal addition, publishers began removing Matt 17:21 from their Bibles with a textual note explaining the inauthenticity of the verse.

So, is there actually a wicked society of scholars slicing up Scripture, removing words and phrases from your Bible to keep you ignorant?

No one, and I mean no one, is intentionally removing verses from your Bible because they are afraid of “prayer [and fasting]” and the purported power it has.10 What seems more plausible, a simple, explainable scribal error that survived for centuries in the manuscript tradition or a conspiracy to remove a verse from Matthew, but the nefarious party left it in Mark, while providing an explanatory note for its exclusion?11

Conclusion

In the next entry on textual criticism, we will explore the types of mss that we possess and how we categorize them. This may not seem all that relevant for assessing the authenticity of a reading, but it is significant for the process.

If you want to learn more about textual criticism and the New Testament, would you kindly subscribe?

As of today (4 Aug), it appears to have over 1M views, and that hurts the soul…

And let’s not even begin to dive into canonicity or the ridiculous conspiracies of Rome removing books from the Bible and stashing them away in the Vatican. The amount of brain deterioration required to believe such hogwash is unbelievable.

R. Brown, An Introduction to the New Testament (New Haven: Yale, 1997), 52 notes the translation of the Vulgate from 1100 years prior was based on better Greek mss. Erasmus also did not have any of the papyri nor did he make use of the major codices.

See B. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, 2nd ed. (New York: United Bible Societies, 1994), xxii.

For instance, Bruce M. Metzger & B. Ehrman, The Text of the New Testament (Oxford: Oxford, 2005).

Metzger, Textual, xxiv writes, “It was the corrupt Byzantine form of text that provided the basis for almost all translations of the New Testament into modern languages down to the nineteenth century. During the eighteenth century scholars assembled a great amount of information from many Greek manuscripts, as well as from versional and patristic witnesses. But, except for three or four editors who timidly corrected some of the more blatant errors of the Textus Receptus, this debased form of the New Testament text was reprinted in edition after edition. It was only in the first part of the nineteenth century (1831) that a German classical scholar, Karl Lachmann, ventured to apply to the New Testament the criteria that he had used in editing texts of the classics.”

This is also because most people do not have the requisite knowledge of Greek even to begin to assess these variants. Not only is the process of textual criticism difficult, if one does not have a solid grasp of Greek grammar and morphology—not to mention an understanding of doctrinal developments—the task is impossible.

R. Brown, Introduction, 53.

The end of the verse, “and fasting,” may not be original. Metzger, Textual, 85 remarks, “In light of the increasing emphasis in the early church on the necessity of fasting, it is understandable that καὶ νηστείᾳ is a gloss that found its way into most witnesses. Among the witnesses that resisted such an accretion are important representatives of the Alexandrian and the Western types of text.”

That is, no textual critic. We will discuss later (entry #3) the scribal tampering of texts.

The number of assumptions one must make to conclude there are individuals attempting to corrupt our knowledge of Scripture is staggering: The textual critics and biblical scholars are in cahoots; the publishing companies have been convinced by these nefarious scholars to delete these verses; and—the most ridiculous—an entire field of study has been created in order to fabricate categories of mss and methodologies to hoodwink even the most intelligent in the field.