The Importance of Properly Employing Greek & Linguistics

An Example of a Linguistic Fallacy from Dr. Kevin M. Young

Introduction

Greek is hard. Learning the morphology is challenging; conquering participles is Herculean; mastering the -μι verbs is Sisyphean. Factoring in the abnormal syntax and the confusing conditionals, reading Greek is a difficult task.

Translating is a beautiful, vexatious art that takes reading to the next level, and this, in part, is due to lexical decision making—lexicography. Choosing the correct word to represent what the author intended for your target reader who—most likely—knows zero Greek can be maddening. There is a difficult balance between honoring the Greek the original author composed while simultaneously making it intelligible for an English reader; quite frequently, there is no simple one-to-one equivalence.

With all these considerations in mind, it blows my mind how arrogant and pretentious X-Twitter “scholars” can be when engaging the laity on the platform concerning Greek and lexical distinctions. The field is well-stocked with disagreements on the meaning of words in various contexts; take for instance the amount of ink spilled in the war over “justice/righteousness” (δικαιοσύνη) in Paul—talk about a minefield.

So, when Dr. Kevin Young arose from bed—angry—the other day and decided to have a mental fistfight in the shower, the result was making an odd lexical statement on Twitter—in English, mind you, then Greek—concerning what it means to repent.

Well, the comment section did not go as planned, or maybe it did. The negative reaction led to a toxic response wherein Kevin decided to flex, citing the Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (TDNT), which is itself a problematic source.1 The other resource he mentions, I have not met before, but really he should have quoted both

W. Arndt et al., A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature (University of Chicago Press, 2000)—Abbreviated BDAG

H. Liddell and R. Scott, Greek-English Lexicon (Clarendon, 1996)—Abbreviated LSJ

And if feeling saucy, F. Montanari, The Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek (Brill, 2015)

He then essentially taunted every dissenter that he knows Greek, and they do not. This, obviously, set people into a frenzy quoting Scripture and posting Strong numbers, which, to be fair, is exceptionally counterproductive. Just because you can use Strong’s and a dictionary does not mean you know Greek or that you are a lexicographer; you are making the same mistake as the doctor.

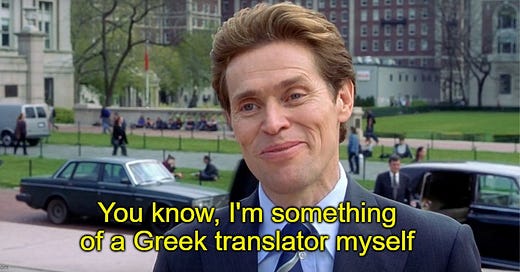

Well Kevin, I, too, know a bit of Greek and linguistics.

First and foremost, I am unclear why you decided to make this statement. It seemingly came out of nowhere, and without any context, it is difficult to truly assess. Be that as it may, I have a twofold response to this bizarre tweet: 1. Lexical and 2. Scriptural.

Lexicographical Issues

The main issue with Kevin’s terse tweet is the assumption he makes, that since the dictionary says μετάνοια (metanoia) means “think differently,” that indicates there is no possible concept of “stop sinning” contained in the word. This is a bit preposterous considering the lexical range words can have in English—Greek is no different. Also, determining the more nuanced meaning of a word is derived based on how it is used in context.2 Yes, at times metanoia can mean “think differently,” but there is a greater range within the New Testament.

Daniel Wallace, a Greek NT linguist, remarks in a post on common linguistic fallacies,

Lexical-conceptual equation: the belief that a concept is captured in a single word or word group or the subconscious transference of a word to the concept and vice versa (like ἁμαρτάνω and sin).

This is precisely what Kevin is attempting to do. He is putting metanoia in a box, stating that there is no room for understanding “repent” to mean “stop sinning.” Now, I am not necessarily stating that “repent” and “repentance” mean “stop sinning,” but certainly this idea is intertwined—at least in the New Testament. This, in turn, would indicate that the sinner should then strive to “stop sinning.” But, we have gotten a bit ahead of ourselves.

If Kevin wishes to narrowly define metanoia in the New Testament, making a limited tweet and then falling back on TDNT and another dictionary does not make for a convincing argument. Rather, the biggest issue I have concerns the lack of context and the inability to prove his own point. Just because a lexicon or dictionary contains a meaning of a word, that does not mean you as the reader/translator can just pick and choose which definition pleases you with the result that the text claims what you want it to. The author’s intent matters.

For instance, in my translation of the Binding of Isaac in Jubilees, I had a brief discussion on lexicography and translating,

When opening a lexicon, you are not free to choose the definition you prefer or fancy; rather, the translator must deduce what the author most likely intended. Context is critical for understanding how words function within a text, and an author is not restricted to just one meaning.

In this particular example, I was showing how κριός (krios) in Genesis 22 (LXX) could be translated as “ram” or “sea monster.” As much as I want to render the text so that Abraham sacrificed a sea monster in place of Isaac, that would be disingenuous as a translator. As such, Kevin cannot just define the word broadly as he sees fit.

A proper approach would have been to pinpoint a text in particular that illustrates that “think differently” is the operative definition in counter distinction to “stop sinning.” I have previously published a paper on a lexicographical topic, specifically the proper interpretation and understanding of οἰκονομία (oikonomia), “household management” (1 Cor 9:17) and οἰκονόμος (oikonomos), “household slave.” In this article, I had to define and show how others translated and understood the term, and then prove how these terms were improperly understood in 1 Corinthians. I did not, in turn, broadly state that oikonomia does not ever in anyway mean “commission” or “divine order”; rather, I narrowly defined the word for how it is situated within the context of this singular epistle—that said, this germ of thought I believe developed within Early Christianity, and it can be witnessed in Ephesians and 1 Clement; I digress.

In order to narrowly define a word to fit one’s position, an argument must be made, and quoting two flimsy sources certainly does not suffice.

Counter Point from Scripture

If we do a quick examination of where metanoia appears in the New Testament, it would be odd to understand each instance of the word to mean just “think differently.” There are about 163 results according to Verbum/Logos, but we shall limit our examination to just one instance.

If we were to translate Matt 3:11a as, “I baptize you with water for thinking differently (μετάνοιαν, metanoia),” that would certainly sound ridiculous. Now, “repentance” here can certainly be understood to include the idea of “thinking differently” in so far as changing one’s idea, perhaps, of who the Messiah is, what the Kingdom of Heaven is, etc. but let’s not stretch a word beyond what is intended in this context.

This baptism is an act of purification; to understand this “repentance” of having nothing to do with sin—this is implicit in Kevin’s suggestion, I believe; otherwise, why make the tweet?—is rather asinine. This is especially the case considering 3:6, “...and they were baptized in the Jordan River by him, confessing their sins.”

Is there an exact definition of “stop sinning” here in Matthew? No, not precisely—again, I think Kevin has created a false dichotomy here. But, to assume that the definition of “repentance” is limited to “thinking differently,” certainly we can agree that Matthew intended repentance to include a confession and renouncing of sin. As Davies and Allison claim concerning v. 11,

...baptism presupposes and expresses repentance (cf. 3:7–10) while it also, through the action of God, issues in a true reformation (cf. Beasley-Murray (v), pp. 34–5).3

If Kevin did not intend to exclude the idea of renunciation of sins or a rejection of sins, he should have clarified rather than bombastically attacking people about Greek. His imprecision, lack of charity, and overall smug attitude led many to disregard any grander point he may have had. I am perplexed by what he hoped to achieve with this tweet, but his modus operandi on Twitter seems to be antagonize and shame rather than educate.

Conclusion

Dr. Kevin Young served more as a springboard than anything else for this post. I truly cannot comprehend why he made this statement other than to embitter people on X-Twitter.

With that said, the main takeaway should be, remain skeptical when someone implements Greek for an argument because they likely have little translating or linguistic training, and its inclusion seldom bolsters their claim. As one of my first Greek professors in New Testament studies once told me, many people know enough Greek to be dangerous. Meaning, they may have taken a couple semester hours of Greek, they can recognize words and phrases, perhaps use a lexicon, they may even be able to translate a sentence or two, but when it comes to an actual analysis of the text, they will bungle the meaning or generate a linguistic fallacy.

How I started this piece I will also end it, Greek is hard. As Edith Hamilton wrote,

...Greek is a very subtle language, full of delicately modifying words, capable of the finest distinctions of meaning. Years of study are needed to read it even tolerably.4

It is not as simple as opening up an interlinear, having Strong’s in one hand and a lexicon in the other, and “interpreting” the Greek. This will most assuredly lead to linguistic fallacies. Learn from Dr. Kevin Young’s bad example: lexicons and dictionaries are tools; they do not definitively prove what a word means. The purpose of these resources is to suggest what a word might mean, but it is up to the translator to decide based on context, authorial intent, and continuity within the sentence, paragraph, and ultimately the document as a whole.

This was written rather quickly; I typically take a bit more time to produce on SubStack. But, I felt the need to at least word vomit onto a page to display my discontent. When scholars are on social media, I believe they should do a better job of representing the field because all this tweet does is further divide the academic community and the laity. Scholars have a lot to offer, but when they haphazardly throw around hot takes like this, it exacerbates an already growing trend of distrust of experts.

If you wish to read more about the New Testament, Greek, and linguistics, would you kindly subscribe?

I cannot hope to delve into the Nazi association of the work, and I will not summarize the linguistic problems of this dictionary. For that, consult James Barr, The Semantics of Biblical Language (Oxford, 1961).

That is not to imply that words have no meaning outside of their context. But, if we do not take into consideration how a word is being used when the author is attempting to convey a particular thought, then we may misread what has been written.

W. Davies and D. Allison Jr., A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel according to Saint Matthew (T&T Clark International, 2004), 312.

E. Hamilton, The Greek Way (Norton, 1930).