The Johannine ‘Aqedah

A Study on the Development of Genesis 22 within Judaism and the Nascent Church | Part 1: Introduction and Jewish Tradition

I have decided to upload my senior thesis onto SubStack since it is an interesting examination on typologies in the Gospel of John, specifically seeing Jesus as a “New Isaac”—to play off of Dale Allison’s The New Moses.

This study will be presented in two parts. This first entry will be the introduction and Jewish background on Isaac. The Second post will be how these themes and motifs appear in the Fourth Gospel.

Nota Bene: The first section on Isaac as an “only” child is a linguistically heavy discussion, which is necessary to establish this feature from both Genesis and John. It is not as engaging, so if you are not concerned with the discussion, feel free to jump to the following section.

Introduction

Within both Judaism and Christianity, Genesis 22 (the ‘Aqedah, עקד, also known as the "Binding of Isaac") played a formative role.1 After its initial composition, the story of Isaac's near sacrifice continued to develop within various Jewish circles,2 which is illustrated in works of the intertestamental period, Qumran, contemporaneous writings of the New Testament, and Rabbinics.3 The authors of the New Testament and the Early Church also partook in this development, for they understood Isaac to be a portent of Christ and his sacrifice.

This study conducts an analysis of how the ‘Aqedah developed linguistically and thematically within these two traditions.4 Ultimately, the earliest Christian writers were heavily dependent on Jewish expansions of the ‘Aqedah in order to speak of Christ's sacrifice—in fact, these authors were reliant on developing tropes that had arisen for numerous Old Testament figures.5 This hermeneutical lens was not restricted to Jesus, but it also influenced how other characters in Jesus' narrative were portrayed, e.g. John the Baptist as the second Elijah—as I recently discussed—and forerunner of the Messiah.6 The influence of the ‘Aqedah on John eventually impacted the earliest Christian calendars, for the Quartodeciman communities framed their paschal season around the Jewish dating of Pesaḥ (פסח, πάσχα), which was 14 Nisan.7

This project systematically presents how numerous aspects of Genesis 22, including its many textual traditions (MT, LXX, recensions, et al.) and later developed tropes in the intertestamental literature, can be found within John's Gospel. These characteristics are both thematic and linguistic. Since this argument is contingent upon a web of connections, it is onerous to present the argument linearly. As such, the study includes two interconnected sections, one being related to early Jewish literature and the later concerning the Fourth Gospel. The initial study includes examining important themes within Judaism prior to, contemporaneous with, and post the New Testament, specifically John. These themes include

A father sacrificing an only (יחיד, ἀγαπητός, µονογενής) son,

Isaac being a willing sacrifice,

Isaac bearing the wood (עץ, ξύλον) for his sacrifice,

Passover, and

the place (םוקמ, τόπος) of Isaac's near-sacrifice—Moriah, where the Temple would later be built.8

All themes presented are not contained within the original account, but these developments became paramount in the Second Temple period. One cannot hope to understand the earliest Christian writings without fully understanding the literature that was being read and circulating within the milieu. With that said, some later texts within Judaism and Christianity will be mentioned since they show later trajectories of these themes. It is impossible to prove that these re-tellings are contingent upon earlier ideas, but they reveal a vein of tradition that John and the other New Testament composers were in.

As for the Gospel of John, I will illustrate how these themes were significant in John's portrayal of Jesus. An Isaac typology is the only means by which an adequate theology of atonement could arise within Christianity, for how else could a cultic sacrifice of a lamb or goat develop into an atoning human sacrifice? The Suffering Servant of Deutero-Isaiah certainly also served as a backdrop, but this figure developed associations with Isaac.9

It is more rarely contemplated how precisely the logic of Christ's sacrifice developed within early Christianity, and I will argue that it is in view of Isaac's near sacrifice. With that said, the aspects that evolved concerning Isaac have their parallel in the Evangelist's representation of the Christ. It is in the Jewish legend of the ‘Aqedah where a father is commanded to sacrifice his son that John found his understanding of what God the Father gave to redeem the kosmos.10

The Jewish Tradition of the ‘Aqedah

The means by which we will explore the key themes and linguistic components for under standing Isaac's place in the Fourth Gospel will be as follows. First, the Hebrew text of Genesis 22 will be examined as necessary, if it bears relevance for the argument. This will then transition into a discussion of the Greek text (Septuagint) and its recensions in order to procure any linguistic as sociations. Thirdly, any intertestamental literature, including first century AD compositions, will be assessed. The final part of each subsection will be concerned with later Jewish and Christian developments that may have relevance for seeing John in a vein of tradition that relied on the ‘Aqedah.11

The Father Who Nearly Sacrificed his Only Son

One of the most defining aspects of Genesis 22 is that Abraham, the father, is ordered to offer up Isaac, his "only" beloved son, as a burnt sacrifice to YHWH in vs. 2,

And he said, "Take your son, your only one,12 whom you love, Isaac, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a whole-burnt sacrifice upon one of the mountains upon which I will tell you."

The parental aspect of this passage is paramount, for it was significant that YHWH commanded Abraham to carry out this act. If Isaac, the child of promise, were to be sacrificed, the covenant cut between YHWH and Abraham would be void. The second aspect of note is that Isaac is described as the "only" (יחיד) child of Abraham.13 As a point of linguistic significance, there is some contention on how יחיד should be translated, as well as its meaning in translation into Greek.

According to HALOT, the primary definition of יחיד is "only," and secondarily "lonely, deserted."14 If the reader examines the cognate evidence, the term is semantically related to Hebrew אחד, one:15 "OSA. wḥd, Arb. waḥīd; Akk. (w)ēdu one, only."16 From this evidence, the only possible problem is the w present at the beginning of the cognates; this is not surprising since initial w in Proto-Semitic typically went to y in Hebrew.17 Therefore, based upon the historical evidence of the term, it is certain that the term connotes that the parent does not have another offspring. The term does not have the sense of "beloved," per se, but its semantic range very well could be understood as such.18

As for the contextual evidence, יחיד has the connotation of "only" in most scenarios, but there may be a slightly larger semantic range. In most of its occurrences, the word is used in connection with an "only" child (Gen 22:2, et al.; Judg 11:34; Jer 6:26; Amos 8:10; Zech 12:10).19 Note, the term can be used formulaically in the context of mourning for a coming destruction, which is exhibited in both Jer 6:26 and Amos 8:10. This is also the case for Zech 12:10, but it is not in the context of future destruction.

Keep in mind, though, that the circumstance is still that of mourning the loss of the one whom they pierced—it will be as mourning for an "only" child. Therefore, these three instances may show that this was a stock expression of mourning in Hebrew,—i.e. eschatological judgement—especially considering how similar Jer 6:26 and Amos 8:10 are, both containing the phrase (אבל יחיד).20

In the Psalms, the term possesses a slightly broader semantic range. Ps 22:21 is translated by the NRSV as "my life," with a footnote stating, "my only one."21 Ps 25:16 is an instance of "lonely" or "deserted," so this falls into the second definition recorded in HALOT. Finally, the NRSV renders Ps 68:7's יחיד as "desolate," and the ESV translates it as "solitary"22—so this, too, is within the parameters of HALOT's second definition. As for Prov 4:3, there is contention on how the term should be translated. In the NRSV, the translation reads,

When I was a son with my father,/ tender, and my mother’s favorite…

whereas the ESV reads,

When I was a son with my father,/ tender, the only one in the sight of my mother.23

Here we can see that there is some discrepancy on how to translate יחיד, and the division is essentially between "only" and "beloved" (favorite). Bruce Waltke comments on v. 3,

Moreover, she cherished him (i.e., regarded him as "the only one" [yāḥîd]), an adjective that brings out prominently his unique and beloved status with her. Though Abraham had other sons, only Isaac is called his yāḥîd (Gen. 22:2, 12, 16) to emphasize the special status of Sarah's offspring. Aquila, Symmachus, and Theodotion captured the thought by Gk. monogenēs "the one and only son" (i.e., "unique," incomparable"; cf. John 3:16; Heb. 11:17]). The LXX renders it "beloved," understanding yāḥîd as unice dilectus.24

From this data, we can postulate that the term most commonly meant "only" when used in reference to a child, but the word could possibly mean "favorite" or "beloved" in some instances (e.g. Prov 4:3).25 In such cases, it is not necessarily so that the onliness of the term has been lost.

Rather, a translation or understanding of יחיד as beloved reflects the overlapping connotations of the word:26 an only child will be beloved since he/she is the only offspring of the parent(s).

The text of Gen 22:2 LXX is problematic in its translation of יחיד, for it does not quite have the same connotation that is present in the Hebrew text,

καὶ εἶπεν Λάβε τὸν υἱόν σου τὸν ἀγαπητόν, ὃν ἠγάπησας, τὸν Ἰσαάκ, καὶ πορεύθητι εἰς τὴν γῆν τὴ ὑψηλήν, καὶ ἀνένεγκε αὐτὸν εἰς ὁλοκάρπωσιν εφ᾽ ἓν τῶν ὀρέων, ὧν ἄν σοι εἴπω.

And [God] said, "Take your only/beloved son, whom you love, Isaac, and go to the high land, and offer him as a whole-burnt sacrifice upon one of the mountains, which I will tell you.

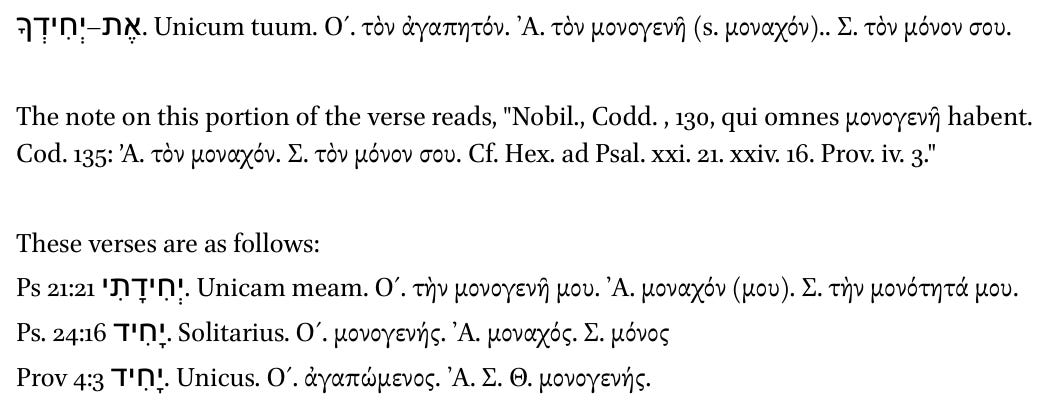

Text critically, the phrase, τὸν ἀγαπητόν, is difficult to assess, since the recensions all contain something other than what is contained in the Septuagint. Origin's Hexapla reads,27

From this, the reader can see that יחיד was not translated consistently, so there was clearly some confusion just how to render the term. ἀγαπητός is an intriguing choice for יחיד since its root is as sociated with an understanding most commonly associated with "love." Some postulate that there is a textual corruption in the Hebrew, so the text should read ידיד, but there is no direct evidence outside of the LXX to suggest this.

Within the Septuagint, though, this is problematic since BDAG lists "only" as a primary definition for the term when used in reference to a child, and LSJ lists it in association with "only" children. It does not state that the term means "only," but "that wherewith one must be content," seemingly because it is the parents' only offspring.

This confusion can be witnessed within the Septuagint, since ἀγαπητός was used to translate both יחיד, "only," and ידיד, "beloved."28 Based upon this, Aquila and Symmachus likely rendered their texts differently from the LXX based upon their uncertainty that ἀγαπητός was an adequate representation of יחיד. Obviously, this is an argument from silence since they do not state this directly, but they each consistently alter the Septuagint's translation of יחיד. Even though ἀγαπητός in classical literature could be used in reference to an "only" child, the term had developed more closely to a meaning similar to ידיד. This is logical, since "that wherewith one must be content" lends itself towards "beloved" over "only," especially when considering its root (αγαπ-).

As I argued previously, יחיד is best understood to mean "only" both historically and con textually. In two of the three instances on child sacrificed to be analyzed, the word יחיד appears, so we shall begin our study with these texts, since they shed light on our understanding of the language in the ‘Aqedah.29

Notice that יחיד is found only in Gen 22:2, 12, 16 and Judg 11:34.30 2 Kgs 3:27 possesses a different word, which is expected since יחיד does not quite possess the same semantic meaning as בכר, which means "first-born." It does not necessarily mean that the offspring is the only one of the parent (cf. Gen 10:15).31

Since 2 Kings 3 contains בכר in the Hebrew, the Greek's preference for a separate lexeme, πρωτότοκον, is unsurprising.32 Of course, all these texts contain the theme of human sacrifice, and with it, the notion of surrendering over an "only" or "first-born" child to death in exchange for some gain.

As was just analyzed, Gen 22:2 has ἀγαπητός, and Judg 11:34 shows a lexical association to this text since both translators rendered יחיד similarly. Note that the translation of Judges includes two adjectives—both ἀγαπητός and µονογενής. This is likely done for emphasis, but it is striking that both terms are used.33

In the Hebrew, there are three ways in which the author reflects that she was Jephthah's only offspring. The use of every term in this context, then, likely contains the same semantic meaning, but different lexemes were employed in the Septuagint since the Hebrew contained this construction.34

Hatch and Redpath make no distinction as to which words ἀγαπητός and µονογενής refer.35 From this evidence, we can state fairly certainly that prior to the first century, ἀγαπητός still contained a meaning associated with "only" when used in reference to a child. Later, by the turn of the millennium, it began to lose this meaning, which is reflected in the alterations present in the recensions of Aquila and Symmachus, but this distinction may have arisen earlier.

In summary, Hermann Büchsel writes, "The LXX uses µονογενής for יחיד, e.g., Ju. 11:34, where it means the only child; cf. also Tob. 3:15; 6:11 (BA), 15 (S); 8:17; Bar. 4:16 vl… The LXX also renders יחיד by ἀγαπητός, Gn. 22:2, 12, 16; Jer. 6:26; Am. 8:10; Zech. 12:10."36

He also contends, "If the LXX has different terms for יחיד, this is perhaps because different translators were at work." If that is the case, then the two terms were understood as having similar lexical values, for if they were starkly different, the two would not presumably be interchanged in translation.37

I am not insinuating, though, that the terms connote the same meaning in every instance that they are employed. In fact, I hesitate from saying that ἀγαπητός ever had the strict notion of "only" (contra BDAG). Rather, it was used in association with only children, implying such an understanding, but the term's meaning lied closer to "beloved."

Be that as it may, there is still quite a bit of semantic over lap between the terms; thus, translators rendered יחיד into Greek either with ἀγαπητός or µονογενής with no large lexical difference, at times.38

The father-son language is also paramount in other literature that mentions or re-tells the ‘Aqedah. These texts also shed some light on how to understand the relationship between the parent and child linguistically. Josephus, Ant. 1.222, states,

Ἴσακον δὲ ὁ πατὴρ Ἅβραµος ὑπερηγάπα µονογενῆ ὄντα καὶ ἐπὶ γήρως οὐδῷ κατὰ δωρεὰν αὐτῷ τοῦ θεοῦ γενόµενον.

And Abraham, his father, loved Isaac exceedingly, since he was his only-begotten son at the threshold of his old age, according to the gift given to him by God.

Herein we see the theme of a love and the only-begotten nature of Isaac. Linguistically, we can see that both terms are used to describe the patriarch. In other texts, there is no descriptor for Isaac besides being called Abraham's "son"; Jub 17:16 reads, "So Prince Mastema arose and said before the Lord, 'Behold, Abraham loves Isaac, his son, and he finds (Isaac) more pleasing than all others.'"39

Lastly, within later literature, multiple descriptors are used, which may indicate that all of them were implemented at various times to describe Isaac.40 Irenaeus, Haer. 5.4 writes,

Δικαίως δὲ καὶ ἡµεῖς, τὴν αὐτὴν τῷ Ἀβραὰµ πίστιν ἔχοντες, ἄραντες τὸν σταυρὸν ὡς καὶ Ἰσαὰκ τὸ ξύλον, ἀκολουθοῦµεν αὐτῷ. Αὐτὸς δὲ προθύµως τὸν ἴδιον µονογενῆ και ἀγαπητὸν παραχωρήσας θυσίαν τῷ Θεῷ, ἵνα καὶ ὁ Θεὸς εὐδοκήσῃ ὑπὲρ τοῦ σπέρµατος αὐτοῦ παντὸς τὸν ἴδιον µονογενῆ καὶ ἀγαπητὸν Υἱὸν θυσίαν παρασχεῖν εἰς λύτρωσιν ἡµετέραν.

And righteously, since we have the same faith as Abraham, we also raise our cross—as did Isaac the wood—and follow him. And he eagerly set aside his own only-begotten and beloved as a sacrifice to God, in order that God also might be pleased to offer his own only begotten and beloved Son on behalf of all his seed as a sacrifice for our redemption.

From this we can see that ἴδιος, ἀγαπητός, and µονογενῆς could all be used in conjunction to describe Isaac. This may not prove any lexical association in the first century, but by the time of Irenaeus (2c. AD), all three words were used, which illustrates a partial linguistic connection. There is also a direct parallel between Isaac and Jesus, which further adds to the interconnected relationship in the Early Church. Although not definitive for the New Testament, there was an early association within the church.

Isaac, the Willing Sacrificial Victim

There is no mention of Isaac's willingness to die in the Hebrew account—he is a silent victim. His only comment prior to the deed is an inquiry concerning the location of the lamb. Therefore, this trope arose after the original composition, and it is present fairly consistently. A number of Second Temple and first century works state or strongly hint that the Patriarch's only son was not a passive participant:41

As for later rabbinic traditions, Tg. Ps.-J. 22.10 reveals that Isaac was not a passive sacrifice.42 Rather, he willingly participates in the horrifying act, and he longs for the deed to be executed:

Abraham stretched out his hand and took the knife to kill Isaac his son. Isaac answered and said to Abraham his father: Bind my hands properly that I may not struggle in the time of my pain and disturb you and render your offering unfit and be cast into the pit of destruction in the world to come.43

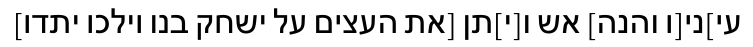

It is difficult for us to date this targum, so it makes the authenticity of Isaac's request to be bound questionable before the first century AD. Be that as it may, there may be evidence of its existence prior to the first century. In the Dead Sea Scrolls, 4Q225 (Pseudo-Jubileesa) frg. 2 col. 2 line 4 may contain this exact idea,44

This was a significant finding since most believed the idea of Isaac requesting to be bound arose in later rabbinic writings. There is some contention on whether כפות is the correct restoration. Geza Vermes, though, shows that the text likely states that Isaac requested that his feet be bound, and therefore the rabbinic tradition is likely dependent upon an earlier belief. He contends,

This speech by Isaac is lacking in Gen. 22. By contrast, as the editors note, the targumic ac count (PsJ, Neofiti (=N), and Fragmentary Targum (=FT), GV) as well as Gen. R. 56:8 (not 7 as in DJD) testify to such an additional speech by Isaac. Of Isaac's opening word only a single letter, clearly a kaph, is legible in 4Q225, but there is space for 15 more letters. However, all the Targums begin with the imperative כפות ("Bind my hands properly"). Cf. also Gen. R. 56:7, כפתני יפה יפה ('Bind me very well'). Hence the reconstruction [פות]כ proposed by the editors enjoys an extremely high degree of probability, but I consider כפות את ידי (cf. Targums) more likely than כפות אותי since את+sufiix is unattested in 4QJubilees and Ps. Jubilees.45

Based upon this evidence, it is at the very least probable that the idea was in circulation prior to the New Testament. Even if 4Q225 does not contain Isaac's wish to be bound, there is substantial evidence of Isaac's willingness to be sacrificed.

Within the Early Church, the atoning sacrifice of Christ had already been paralleled with Isaac's passion as early as the Apostolic period,

…and he was intending to present the vessel of his spirit as a sacrifice on behalf of our sins, in order that the type that was established by Isaac, who was presented upon the altar, might be brought to fulfillment (Barn. 7.3).

Although there is no association with willing sacrifices in the Epistle of Barnabas, 1 Clement provides a belief that Isaac willingly participated,

With boldness (πεποιθήσεως), Isaac, since he knew the future, was brought willingly (ἡδέως) as a sacrifice (θυσία)" (31:3).

From this the reader can see that there were at least variegated associations between Christ and Isaac, and they were employed for different means.46

Isaac Bore the Wood for his Sacrifice

Isaac bearing the wood for his own sacrifice has its foundation within the Genesis text,

And Abraham took the wood for the whole-burnt offering and placed it upon Isaac, his son, and he took the fire and the knife in his hand, and the two of them went together.

Although there is nothing too significant in the text itself, this tradition carried on throughout the retellings of the legend. Jub. 18.5 reads,

(Abraham) took the wood for the sacrifice and placed it upon Isaac, his son's, shoulders, and he took in his hands fire and a dagger. The two of them went together up to that place.

Although this text is almost identical to the Genesis account (in both the Ge‘ez and Hebrew), it reveals that it was important to retain this part of the text. 4Q225 frg. 2 col. 2 line 1 reads,

his ey]es [and there was] fire, and he pl[ac]ed [the wood upon Isaac, his son, and they went together.]

From this, the reader can see that it was a regularly occurring characteristic to describe Isaac as bearing the wood for his own passion. Philo (Abr. 171–72a), though, offers an explanation for why Abraham chose to have Isaac carry the wood,

τῷ δὲ παιδὶ πῦρ καὶ ξύλα δίδωσι κοµίζειν, αὐτὸ δικαιώσας τὸ ἱερεῖον τὰ πρὸς τὴν θυσίαν ἐπηχθίσθαι, κουφότατον βάρος· οὐδὲν γὰρ εὐσεβείας ἀπονώτερον.

But he gave to his child the fire and wood to carry, because he thought it right that the victim himself bear the instruments for the sacrifice—a lighter burden—for nothing is less onerous than piety.

In Philo, it is Isaac's duty to carry the tools for sacrifice because he is doing it for God—there is no greater honor. The act is ultimately Isaac showing his loyalty to God, and this is arguably similar to him being willing to sacrifice himself. This is not directly so because Philo expresses this thought through Abraham's self-reflection. Regardless, Isaac's willingness is significant.

Although it is a common facet of the retellings, it is not always present. Josephus, Ant. 1.227, chronicles no bearing of wood; he only states "And they bore with them as much was needed for the sacrifice except for the victim (ἱερείου)."47 Demetrius the Chronogropher, Fragment 1; Eusebius, Praeparatio evangelica 9.19, records,

Polyhistor (says) a great quantity (of things); to which he adds after other (sentences), "But not after much time, God commanded Abraham to offer Isaac, his son, to him. And after he lead his son up upon the mountain, he heaped up a pyre and placed Isaac (upon it).

Therefore, it should be noted that these characteristics are not present in every text. The reader can see, though, that it does occur frequently, which indicates that it was important for later interpretations. Targum Pseudo-Jonothan and Targum Neofiti record verse 6, obviously, but neither author offers further explanation. Lastly, Gen. Rab. 56:3 speaks of Isaac carrying the wood was similar to bearing a cross.48

Finally, the tradition takes its fullest form in Patristics wherein the Patriarch and Jesus are paralleled. Tertullian, Adv. Jud. 10.6, writes:

So, principally, Isaac was led by his father as a sacrificial-victim (hostia), and, when he bore (portans) his own wood (lignum), then at that time he pointed to Christ's death. As a victim (victimam) submitting to his father, he carried (baiulantis) the wood (lignum) of his own passion (passionis).

This quotation exhibits the common trope that Isaac prefigured Christ by carrying his own ξύλον (here, lignum). Since Tertullian composed in Latin, the lexical connection is not as apparent, but the idea still persists.49 This text illustrates that Tertullian believed Isaac's sacrifice was a portent for Christ's own passion.

Clement of Alexandria speaks similarly,

But he was not offered as a sacrifice (κεκάρπωται),50 as was the Lord; Isaac only bore the wood (ξύλα) of the sacrifice (ἱερουργίας), as the Lord [bore] the wood (ξύλα) (Paedagogus 1.5.23).

This is an important development in Christian understanding that the mentioning of "wood" could serve as a substitution for the cross (σταυρός).51 In both of these accounts, the authors believe that Isaac performed portentously, pointing ultimately forward to Christ.

Isaac, the Paschal Sacrifice

The derivation of the most ancient Israelite festival practice originates in Exodus 12. The text commemorates Israel's freedom from bondage and flight out of Egypt. This is a reoccurring appeal in Old Testament literature since it was a foundational memory within the Jewish tradition.52

The actual origins of this festival and its context are not as relevant for this study,53 but it is necessary to explore the textual tradition found within Exodus since it influenced the practice in the Second Temple Period, Christianity, and the Early Church.54

Exodus 12 records not just one celebration, but two: Pesaḥ (Passover) and Maṣṣôt (Festival of Unleavened Bread).55 How the two are related historically is contested. Regardless,

Late monar chic centralization of worship… would create a rupture between Pesaḥ and Maṣṣôt, as well as an exchange of status. Pesaḥ became a Temple sacrifice, Maṣṣôt a domestic observance.56

This text is significant not only for the sacrificial observance, but also because it redefined the calendar year (12:2). "The entire religious calendar of Israel is henceforth to reflect this reality by numbering the months of the year from the month of the Exodus."57 If a group rearranges their relation to time and space based on one event in history—and it becomes a constant appeal—it must be significant.

A number of key elements to note include the selection of a lamb (v. 3; Heb. שה, Gk. πρόβατον) and the date on and time at which the sacrifice occurred (v. 6; 14 Nisan).58 The slaughtering of the lamb was a twilight ritual wherein each family of the Israelite community acted at once.59 The precise day when the sacrifice occurred is slightly confused due to the reckoning of time in Jewish practices; twilight on the fourteenth day would technically be 15 Nisan, the day on which Israel fled Egypt.60

As for the animal, שה can indicate either a sheep or a goat.61 The distinction is not made explicitly in the Septuagint, for the translator rendered שה as πρόβατον.62 As for the prophets and later literature (e.g. Isa 53:7), sheep must be in mind for the term since it is sporadically paired with ἀµνός (“lamb”). Based upon this translation, the custom held that sheep were to be sacrificed on 14 Nisan prior to the first century.63

Originally, there was no link between the ‘Aqedah tradition and Passover.64 Nevertheless, as time progressed, there arose a tradition that Passover and Isaac's near-sacrifice were connected. The earliest and strongest case for this comes from Jubilees, a book that is concerned with calendars and dating.

Jubilees, originally composed in Hebrew between 161–140 BC,65 is an important text for the development of Second Temple thought concerning the ‘Aqedah and Pesaḥ. Jub. 11:1–23:8 chronicles haggadic stories concerning Abraham's life as told in Genesis, and the story of the ‘Aqedah is recounted in 17:15–18:19. 17:15 establishes the parameters of the account; the author states that Mastema brought charges against Abraham before God in the first month on the twelfth day.

From there, 18:1–2 states God's command to Abraham, which is akin to Gen 22:2,

Take your son, your beloved, whom you love—Isaac—and go to the high land, and offer him as a sacrifice upon one of the mountains, which I will show you.

Upon hearing the word of the Lord, Abraham sets forth "at day break" (so, the next day) on his journey with Isaac and two servants. The author then recounts that Abraham chopped the wood for the sacrifice "on the third day," which is the final temporal marker prior to the binding (18:3b).

We are now able to establish a timeline: Mastema approaches God on the twelfth of the first month, Abraham left at day break (the thirteenth), and it is "on the third day" (the fourteenth) that the sacrifice occurs; in the narrative, it is currently the fourteenth of the first month (Nisan).66

Thus, there is a temporal correspondence between the ‘Aqedah and Pesaḥ.67 The conclusion is that the author knowingly connected the two.68 This is made more explicit when Isaac asks Abraham where the lamb is for sacrifice. Abraham responds, "God will see for himself a sheep for the sacrifice, my son." (18:7). The punctuation in English is deceptive. Abraham is either using "my son" as shown above, or the text is playing on the ambiguity; the passage could also read, "the Lord will see about the lamb for the burnt offering, i.e. my son."69 Isaac is thus also paralleled with the paschal lamb.70

Lastly, the Palestinian Targum on Exod 12 speaks of "four nights," which have their foundation on the day when Israel fled Egypt.71 In Jewish memory, these four events all occurred on the same night of the year. These occasions include: (1) Creation; (2) the ‘Aqedah; (3) the flight from Egypt/Pesaḥ;72 and (4) the end of the world/the coming of the Messiah.73 Accordingly, we have Jew ish attestation that combines all of these themes in one location, though the dating of the source is uncertain.74

The Near Sacrifice of Isaac on Moriah, the Place of the Temple

Historically speaking, the name of the location is lost to us. It has been corrupted through transmission, so it is impossible to reconstruct where the event is purported to have taken place. Nahum Sarna writes,

As a matter of fact, the presence of the definite article in the Hebrew (lit. "the Moriah") greatly complicates the possibility of moriah being originally a proper name, since in Hebrew usage the definite article is not attached to proper names.75

Further, Gerhard von Rad states,

The name Moriah was perhaps inserted into our story from II Chron. 3.1 only subsequently in order to claim it as an ancient tradition of Jerusalem (perhaps only with a slight change in the vocalization of an ancient name). The ancient name, later suppressed, could be pre served in the Syriac translation of the Old Testament.76

Therefore, it is a difficult reconstruction due the word's possible inauthenticity.77

John Skinner claims the attempt to explain the name and place are futile. He asserts that the simplest reconstruction is hā’mōrî and that there is no certainty this is even in Israel if the name is ancient.78 Skinner's reconstruction, though, fails to explain the long o, since it would not have occurred at this time, unless he postulates the name existed prior to the Canaanite shift. Secondly, the hireq yod at the end of his reconstruction is left unexplained. It is illogical to assume that the final yod would be a mater since the MT has a dagesh.

Gordan Wenham contends the name plays a role in the narrative, since it looks forward to a positive ending.79 Jon Levenson reports,

As we have had occasion to observe, there is an opinion among scholars that "the land of Moriah" in Gen 22:2 is not original to the narrative of the aqedah but was interpolated in Second Temple times in an effort to associate Abraham's altar with David and Solomon's foundation of the great shrine atop Zion, the Temple Mount here named Moriah. Whether or not this be so, we must see in the name "Moriah" an effort to endow Abraham's great act of obedience and faith with ongoing significance: the slaughter that he showed himself prepared to carry out was the first of innumerable sacrifices to be performed on that site.80

It is is worth noting that the development of Moriah being the place where Solomon's Temple was constructed may have occurred early in Israel's memory.81 If we examine 2 Chron 3:1, the reader will note that there is already an association with this location.

And Solomon began to build the House of Yhwh in Jerusalem on Mount Moriah, which was seen by David,82 his father, at which place David had appointed, on the threshing-floor of Ornan the Jebusite.

Here, though, lies a different justification for why Solomon constructed the House of YHWH there—it is because the Lord appeared to David at this location. There is no mention of the ‘Aqedah explicitly, which is surprising if the name is original to Genesis 22. Edward Curtis and Albert Madsen claim that the name "Moriah" is likely a textual corruption in Genesis, but its implementation occurred prior to the writing of Chronicles.83

If this is the place where the Lord was to receive sacrifices, would not the legend of Isaac's near sacrifice have served as prime justification for the location of the Temple? Sara Japhet writes,

Three separate locus traditions appear in earlier biblical sources, each having its own foothold in the context of the Israelite cult: a mountain in the land of Moriah, where Abraham bound Isaac (Gen. 22); a threshing floor in Jerusalem where the plague was halted and David built an altar (II Sam. 24); and the Temple in Jerusalem, built by Solomon at an unspecified place (I Kings 6). The name "Mount Moriah" is not found in the Genesis ac count (nor elsewhere in the Bible), but here the allusion to the mountain on which Abra ham was bidden to sacrifice his son is unmistakable. That the place of Abraham's trial is al ready identified with the Temple Mount in the aetiology (cf. TJ on Gen. 22.14; the Midrash, Rashi on Gen. 22.2, etc.); whether this is the correct interpretation is still a debated point.84

Japhet later states that it is logical to assume the Chronicler is referring to the Binding of Isaac since God appeared to Abraham and the ram was sacrificed. Even so, she emphasizes the role of David in the account because "Davidic authority… superseded the ancient traditions of the Abrahamic cult."85

In addition to the ‘Aqedah associations with this verse, Ralph Klein states, "יהוה יראה is a play on words on Moriah (המריה), as is יהוה יראה at the end of the verse. Cf. also Gen 22:8: יהוה יראה is a 'Yahweh will provide [the lamb for the burnt offering].'"86 Since the play on words occurs in both passages, it seems likely that the Chronicler wrote what he did to reflect the Genesis account.87 Lastly, Klein also notes that "the mountain of Yahweh" is commonly associated with the Temple Mount (cf. Isa 2:3//Mic 4:1; Isa 30:29; Ps 24:3; Zech 8:3),88 so the association in other texts may have Moriah in mind. Isaac Kalimi suggests

In other words [in v. 14b], the narrator-redactor made a definite but anachronistic connection between "the mount of the Lord" known to his readers and "that site," "on one of the heights" in the "land of Moriah" called by Abraham "ה' יראה." In this way, he sets the story in a place of some importance in the world in which he lived and even imparted to the Temple Mount an additional measure of sanctity as a place chosen for sacrifices (animal sacrifices, to be precise) in the earliest antiquity.89

Therefore, this study concludes that Moriah may not be original to the account, and the actual location of the ‘Aqedah has been lost in Jewish memory. Since the name is difficult to recon struct and adequately explain, it may be a borrowed location from a later time. In all probability, though, "Moriah" is an old primary tradition; the redactor was uncertain of its derivation so he created an etymology as best as he was able (v. 14). Regardless, the name did eventually become associated with the Binding of Isaac, and it played a role in the development of the tradition in the Second Temple period.90

This concludes the first half of the analysis. The second portion of this study will be on how these themes and motifs appear in the Gospel of John.

If you have enjoyed this examination thus far and wish to learn more about the NT, would you kindly like this post, comment, and subscribe?

All translations of Greek, Hebrew, Latin, Ge‘ez, et al. are my own unless otherwise noted.

The account also developed within Islam; consult S. Schreiner, "‘Aqeda," 140–157; F. Leemhuis, "Ibrāhīm's," 125–40.

Many of these evolutions fall into the category of re-written bible. For more on this subject, consult J. Kugel, "Beginnings," 11 and G. Brooke, "Rewritten," 2:777–81.

In the earliest period of "Christianity," it is inappropriate to treat "Judaism" as something completely divorced from this new movement. If anything, Christianity was just a new sect within Judaism, and both groups continued to interact and influence one another. Therefore, any reference henceforth to "Judaism" or "Christianity" is purely nominal. I do not mean to imply that one can speak of these two groups monolithically—both were composed of so many sub-groups that it would be erroneous to speak of them as such. For a synopsis on Christian relations with Jewish communities—from the perspective of Matthew's Gospel—consult G. Stanton, Gospel, 113–145. The connection between Judaism and Christianity is clear, as Alan Segal, "Matthew's," 4 contends, "I wish to show that the earliest Christian community is not yet distinct from the Jewish community; it was a fractious and interesting new sect. By understanding what is happening at Antioch [Gal 2:11–18; Acts 15], we also learn something about Judaism."

For instance, Moses is an excellent example. See D. Allison, The New Moses.

Morris Faierstein, "Why," 75–86 contends that Elijah as a forerunner was not widely known or accepted in the first century AD, and that the tradition may have been a Christian invention. Dale Allison, "Elijah," 256–58 questions Faierstein's conclusion that the idea was a Christian fabrication. In point four, Allison discusses the John/Elijah parallels and the possible rabbinic responses to this belief.

It was once believed that the 14 Nisan observance was an aberration, but the consensus has shifted, and 14 Nisan is perhaps the earliest date for Pascha. See P. Bradshaw and M. Johnson, Origins. For a dissenting view, consult A. McArthur, Evolution, 98–107; J. Jungmann, Early, 25–26. Even though 14 Nisan is associated with the Jewish Pesaḥ, which is chronicled in Exodus 12, associations arose between the ‘Aqedah and Passover. This will be explicated later.

On the Quartodeciman controversy and the Jewish/Johannine influence on this community, see my article, "The Johannine Tradition as 'Apostolic' Evidence for Early Christian Pascha Observation in the Quartodeciman Churches."

There are many other paramount developments that surround the ‘Aqedah that have not and could not be explored in this study. Peruse S. Spiegel, Last; S. Long, Sacrifice 104–34 for additional evolutions of the legend.

Consult P. De Andrado, Akedah. Although the Suffering motif is paramount for discussing this topic, my thesis focuses on the importance of Isaac, and space does not permit a full discussion of Deutero-Isaiah. Roger Le Déaut, Nuit, 205 contends that there is a possible "jonction des deux figures d'Isaac et du Serviteur."

Two early works that must be mentioned concerning the influence of the ‘Aqedah in the New Testament include H. Schoeps, "Sacrifice," 385–92 and N. Dahl, "Atonement," 15–29. Both of these works focus more on Paul, but they trace similar strands that I examine in this paper. See also L. Huizenga, New, who contends that Isaac plays a role in Matthew's portrayal of Jesus.

Art is another important hermeneutic that could not be explored in this project. Consult G. Anderson, "Akedah," 43–61; E. van den Brink, "Abraham's," 140–51; S. Long, Sacrifice; J. Milgrom, Binding.

Or, "your only son."—See here for a full translation and grammatical breakdown of Genesis 22.

This is certainly not the case considering the birth of Ishmael in Genesis 16.

L. Koehler, et al., Hebrew, 406–7. Henceforth, this resource will be cited as HALOT.

Though, perhaps this is not quite the case; H.-J. Fabry, "יחד," TDOT 6:41 notes, "Although the root y/wḥd is found in almost all the Semitic languages, its etymology has always been disputed. On the basis of a relationship with → אחד ’eḥāḏ [’echādh], the meaning 'one,' 'single,' 'unique' has been suggested. This traditional theory postulates a triliteral root, such as appears in the majority of instances. But the biliteral form ḥad, fem. ḥeḏā’, 'one,' found primarily in Aramaic, must then be explained as a consequence of the loss of a compound shewa before ḥ…"

HALOT, 406. H.-J. Fabry, "יחד," TDOT 6:41 writes, "The earliest occurrences of the root yḥd are found in Ugaritic texts. Here yḥd means 'alone,' 'sole,' or (as in later usage at Qumran) 'community' in the religious sense."

As for the historical reconstruction of יְחִֽידְךָ֤ (qatil pattern; consult J. Fox, Semitic, 187) to the ninth century, the accent would have shifted to the ultima, which would have then caused the propretonic syllable to reduce from a to ĕ (*yaḥīdk(ā) > *yĕḥīdk(ā)). The yod after the dalet is an internal mater, which only marks a long vowel (thus, the root is יחד); this yod is not part of the root—internal maters did not arise until later in the orthography (the epigraphic evidence reads, יחד; J. Hoftijzer, Dictionary). The cognate evidence indicates that the initial yod was likely an initial waw in Proto-Semitic, which further shows its relation to an original meaning associated with semitic "one" or "only."

As for אחד, its cognate evidence differs from יחידי: "Ug. aḥd, f. aḥt, Ph. אחד, f. אחת, Arm. חד (→ BArm. MdD 116a), Eth. ʾaḥadū, Akk. (w)ēdu" (HALOT, 29). Regardless, the two words have two radicals in common and their definitions are semantically related, which probably indicates that the two words are etymologically related. H. J. Fabry, "יחד," TDOT 6:42 summarizes the semantic development of the root by de Moor as follows, "the basic meaning is not 'together,' nor does it develop via 'all'—'all one' to 'alone,' as suggested by Gosdman; it is in fact 'one': as a verb, 'be one,' as a noun, 'unity,' 'entirety.' The semantic development then moves from corporative 'be together' through 'together (apart from others)' to 'alone.'"

Judg 11:34 states clearly that יחיד indicates that it was Jephthah's only child. Though, J. Sasson, Judges, 435 translates the verse, "There was only her, a beloved child; beside her, he had no son or daughter." He also states, "As if two notices about the daughter's uniqueness are not enough, the narrator attaches yet another qualification: ’ên-lô mimmennû bēn ’ô-vat" (439). From this, Sasson understands רק as "only" and יחיד as "beloved," akin to the Septuagint. Contrarily, "beloved" may be in mind, but the repetition is for extreme emphasis.

The evidence is far too limited to say for sure, but three instances of mourning out of twelve is compelling. This is even more the case when the reader notices that in three instances out of seven, when the word is used in reference to a child, the context is mourning—especially when three of these instances derive from Genesis 22. Statistics are not conclusive evidence, but it is one measure of assessing how the term was used. H.-J. Fabry, "יחד," TDOT 6:46 speaks of the term similarly.

Ps 35:17 also is translated as "my life," but lacks a footnote.

The Greek in Sinaiticus contains µονοτροπους, which is in agreement with 67:7 LXX.

William McKane, Proverbs, 216 translates it as "an only child."

B. Waltke, Proverbs, 278.

Crawford Toy, Proverbs, 85 contends, "The only child also is improbable; an adj. like the beloved of the Grk. would be appropriate; but this sense (RV. only beloved) does not properly belong to the Heb. word here used; the expression as an only child would be in place."

Michael Fox, Proverbs, 173 remarks, "Yaḥid (lit. 'alone,' 'unique') connotes being especially precious and 'beloved,' as the LXX renders the term several times. A lone child has all his parents' attention and focused affection. Hence even when a child is not actually an only child, he may be called 'alone' to emphasize his dearness (Naḥmias et al.), as in the case of Isaac, for example (Gen 22:2; etc.)."

The Göttingen Septuagint's critical apparatus contains, "τὸν ἀγαπητόν] α´τὸν (> M 344) µονογενῆ (-ννη 413) Μ 57-413(s nom) 130-344; α´τὸν µοναχόν 135; σ´ (+ τον 135 57) µόνον σου Μ 135 57´ 130-344."

For the full list, see E. Hatch and H. Redpath, Concordance, 7.

This is supported by O. Boehm, "Child," 149.

Ps. Philo, L.A.B. 40.3 reads, "…if I did not offer myself willingly for sacrifice, I fear that my death would not be acceptable or I would lose my life in vain." Verse 5 states, "that a ruler granted that his only daughter be promised for sacrifice," which mentions that she is Jephthah's only daughter. Translation from D. Harrington, "Pseudo-Philo," 2:353.

See "בכר," HALOT, 130–31.

This is the most common translation of בכר ; see E. Hatch and H. Redpath, Concordance, 1237. בכר is not listed for either ἀγαπητός or µονογενής (ibid. 7, 933). For a more complete study of בכר , see M. Tsevat, "בכר ," TDOT 2:121–27. He provides a full discussion of how the word means "first-born" in multiple contexts.

Susan Niditch, Judges, 130 writes, "A and OL add 'his beloved,' influenced by the other child sacrifice in Gen 22:2 and perhaps by early Christian interpretations of that scene."

The repetition of semantically related words is not uncommon, cf. Plato, Laws 11.918e.

E. Hatch and H. Redpath, Concordance, 7 and 933.

H. Büchsel, "µονογενής," TDNT 4:740–741.

M. Boismard, Moses, 111 argues, "But in the Greek of the Old Testament, the two terms µονογενής and ἀγαπητός are interchangeable and both translate the same word in Hebrew, יחיד.

Consult L. Kundert, Opferung, 50–56. He states later in note 67, "MS Athos Λαύρα 352 – dieses MS ist bereits oben durch seine spezielle Wiedergabe von יחיד durch µονογενής und ἀγαπητός aufgefallen" (1:99).

Note also Demetrius the Chronographer (Fragment 1; Eusebius, Praeparatio evangelica 9.19), "God commanded Abraham to offer Isaac, his son, to him…"

Clement in his Paedagogus (1.5.23) parallels Christ, the Lamb, and Isaac, specifically emphasizing the parallel sonship of both Jesus and Isaac.

These examples and translations are taken from J. Kugel, Bible, 174–75. Within Islam, there is a similar tradition about Ishmael. R. Hassan, "Eid," writes on Sūrat al-Ṣāffāt (37): 100–111, "What this narrative stresses is the obedience of both Abraham and Ishmael who symbolize what it means to be 'Muslim.'"

Notes from the chart:

42—This translation is from the RSV.

43—The text expounds further that Isaac was so zealous that he "rushed (ὥρµησεν) to the altar and his slaughtering (σφαγῆν)" (1.232).

Texts also focus on Abraham's faithfulness: 1 Macc 2.52; Jub. 17.15–16; 18.16; Philo, Abr. 262; Heb 11:17; 1 Clem. 10:1.

The translation is from G. Vermes, Scripture, 194. Tg. Neof. 22.10 contains a similar sentiment, "Isaac answered and said to his father Abraham: 'Father, tie me well lest I kick you and your offering be rendered unfit and we be thrust down into the pit of destruction in the world to come.'"

The Hebrew text comes from J. Kugel, "Exegetical," 74.

G. Vermes, "New," 142 n. 12.

For instance, Melito of Sardis compares Christ to Isaac (Peri Pascha §59, 60) and to the ram caught in the sabek tree (Fragment 9). Secondly, Melito of Sardis' Peri Pascha §59, 60 and Irenaeus' Fragments from Lost Writings 53 discuss the law and the prophets, and then discloses how numerous patriarchs are connected with Christ. The earliest interpreters were perfectly comfortable having multiple parallels and metaphors working concurrently.

LSJ records victim or animal for sacrifice for this term. I have chosen "victim" for ambiguity, but the text states that Abraham hoped for an animal to be provided.

R. Brown, John, 2:917.

The Gen 22:6 Vulgate reads, tulit quoque ligna holocausti et inposuit super Isaac filium suum ipse vero portabat in manibus ignem et gladium cumque duo pergerent simul.

See the Septuagint usage of καρπόω; LSJ καρπόω: A.2, "offer by way of sacrifice, LXXLe.2.11; ἐπὶ τοῦ βωµοῦ, of burnt offerings, SIG1025.33 (Cos, iv/iii B. C.):—so in Pass., ib.997.9 (Smyrna), cf. Hsch."

There is also a New Testament parallel in Paul that makes this jump. In Gal 3:13 Paul argues, "Christ liberated us from the curse of the Law by means of becoming a curse on our behalf because it is written, 'Cursed is everyone who is hung on a tree (ξύλον)'" (citing Deut 21:23). Constraint limits this conversation to a few words, but the reader should note that Paul in this passage also mentions Isaac as the "seed" in connection with Christ. Now, there is no ‘Aqedah language underlying the text, but it is still crucial that crucifixion is bound up with Isaac.

Thus, as I will argue later, if a New Testament author can substitute cross for ξύλον, the converse is plausible. It has no explicit attestation in the New Testament, but the Church Fathers here are shown to make the move. This also occurs in 1 Pt 2:24, ὃς τὰς ἁµαρτίας ἡµῶν αὐτὸς ἀνήνεγκεν ἐν τῷ σώµατι αὐτοῦ ἐπὶ τὸ ξύλον. Strikingly, ἀνήνεγκεν is the translation in Gen 22:2 LXX for Abraham taking his son to Moriah for sacrifice.

One final point of interest concerns Jer 11:19 LXX: ἐγὼ δὲ ὡς ἀρνίον ἄκακον ἀγόµενον τοῦ θύεσθαι οὐκ ἔγνων· ἐπ᾽ ἐµὲ ἐλογίσαντο λογισµὸν πονηρὸν λέγοντες Δεῦτε καὶ ἐµβάλωµεν ξύλον εἰς τὸν ἄρτον αὐτοῦ καὶ ἐκτρίψωµεν αὐτὸν ἀπὸ γῆς ζώντων, καὶ τὸ ὄνοµα αὐτοῦ οὐ µὴ µνησθῇ ἔτι. I want to pay homage to Melito of Sardis who references this verse in his homily, Peri Pascha.

See Exod 20:2; Lev 26:13; Num 15:41; Deut 5:6; 2 Kgs 17:7; Ps 81:10; Isa 45:3; Mic 6:4; Amos 2:10.

For the development of the Jewish Pesaḥ, see W. Propp, Exodus, 1:429; B. Childs, Exodus, 186–95; and C. Leonhard, Jewish, 1–27.

Ambrose contended that the Passover took place at the beginning of spring just like when creation occurred (Six Days of Creation 1.4.13; so also Martin of Braga, On the Pascha 7); Pseduo-Macarius held that the first month of the Jews corresponds to the first month for Christians because that is the day that the Jews fled from Egypt and when Jesus was resurrected (Homily 5.9); the paschal lamb prefigured Christ (Cyril of Jerusalem, Catechetical Lecture 12.1; Bede, Homilies on the Gospels 2.3); the lamb's blood and Christ's were connected (John Chrysostom, Baptismal Instructions 3.14); and the lamb was sacrificed at night because the Lord suffered at the end of the ages (Jerome, Homily 91).

The Old Testament passages that make reference to these festivals include Exod 12–13; 23:15; 34:18; Lev 23:4–8; Num 9:1–15; 28:16–25; 33:3; Deut 16:1–8; Josh 5:10–15; 2 Kgs 23:10–14; Ezek 45:21; Ezra 6:19–22; 2 Chr 30:1–27; 35:1–9.

W. Propp, Exodus, 428. Also, in post-biblical times, the two were fully integrated; consult B. Bokser, "Unleavened Bread and Passover, Feasts of," ABD 6:755.

N. Sarna, Exodus, 54.

See also Ezekiel the Tragedian, Exogōgē lines 175–180, which instructs the people to sacrifice the lamb on the evening of the fourteenth.

M. Noth, Exodus, 95.

See B. Childs, Exodus, 196.

Consult N. Sarna, Exodus, 54. HALOT's first definition is sheep, but a ram or a goat are viable possibilities.

LSJ defines πρόβατον as small cattle, sheep and goats. T. Muraoka, Greek-English, 584–85 provides: any "small livestock" such as a sheep or goat (see Gen 27:9; 30:32; Lev 1:10), or a sheep offered as a cultic sacrifice (Gen 4:4; Lev 17:3; Hos 5:6). See also BDAG for a fuller discussion of "sheep" in the New Testament.

Concerning the date of the LXX, consult J. Dines, Septuagint.

Though, G. Vermes, Scripture, 215 states: "there is evidence that the association of the Akedah with Passover was established well before the beginning of the Christian Era." Craig Koester, Symbolism, 221 notes that an association between the paschal lamb and the suffering servant arose within Jewish tradition.

For a fuller discussion of the original language and dating, see O. S. Wintermute, "Jubilees," 2:43–44.

Here is my full translation of this section in Jubilees.

The only festival on this day that lasts seven days is Pesaḥ; consult Lev 23:5–8.

See also J. Levenson, Death, 177. For a dissenting position, consult Leonhard, Jewish, 234ff. Leonhard contends that the image is forced, and the reference is instead to Maṣṣôt. Based upon 18:18–19, Leonhard may be correct, but Leviticus 23 also speaks of Passover as a seven day festival.

Consult R. Brown, Death, 1438.

The wording here relies on Gen 22:8; unfortunately, the Greek and Latin of Jubilees 18:7 is not extant. The LXX reads, Ὁ θεὸς ὄψεται ἑαυτῷ πρόβατον εἰς ὁλοκάρπωσιν, τέκνον. Presumably, the translator of Jubilees follows the Septuagint, but this is speculation. If the author did provide πρόβατον for "lamb" or ἀµνός, the parallel is stronger.

Antti Laato, Who, 248–52 argues for a connection between the Suffering Servant and the paschal lamb in early Christian writings. Even if this association is absent in Jewish literature, the connection still could have arisen in earlier Christian circles.

For more on this Targum and Pascha, see R. Déaut, Nuit.

H. Mbachu, Abraham, 39 states, "The lamb 'without blemish, a male of the first year' (Ex 12,5) is related to the lamb of Gen 22,8" in the Exodus Midrash Rabbah.

Gale Yee, Jewish, 57 writes, "By the time of Jesus it was highly likely that the Passover feast and its rich symbolism took on messianic overtones."

Each "night" is a major factor in the Gospel of John: (1) Creation is found in association with Christ in John 1; (2) the ‘Aqedah plays a crucial role in John as will be assessed later, but 3:16 is one example since it contains lexical parallels with Genesis 22; (3) Pascha is a major theme since Jesus is sacrificed on the Day of Preparation in 19:4 and the festival is referenced throughout; and (4) the gospel recounts the coming of the Messiah. Thus, there is a common tradition or thought that exists between John and the poem of the Four Nights. It is impossible to say that John is working within this framework knowingly, but it is intriguing to note that the gospel contains all of these elements.

N. Sarna, Genesis, 391–92.

G. von Rad, Genesis, 240. See also H. Gunkel, Genesis, 238 and J. Levenson, Death, 174.

Julius Wellhausen, Composition, 19 argues there is corruption, and he postulates that the original name was ארץ המורים, "land of asses."

J. Skinner, Genesis , 328–29.

G. Wenham, Genesis, 2:104.

J. Levenson, Death, 174.

This trend exists also in the first century. Josephus, Ant. 1.226, reports that it is upon this mountain that the Temple was built: "After he left his associates in the plane, he was with his only (µόνου) son, [and] they came to the mountain (ὄρος) upon which David the king later built the Temple (ἱερόν)."

LXX adds "the Lord," which indicates that the translator believed that YHWH appeared to David there.

E. Curtis and A. Madsen, Chronicles, 323–24.

S. Japhet, I & II Chronicles, 551. For a similar view, consult R. Klein, 2 Chronicles.

S. Japhet, I & II Chronicles, 552. J. Davila, "Moriah," ABD 4:905 contends "There is not indication that the writer of 1 Chr 3:1 was aware of any connection between Abraham and Mt. Moriah; he only mentions its association with David and Solomon. Surely he would have referred to the binding of Isaac if Moriah has appeared in Genesis 22 in his time (von Rad Genesis OTL, rev. ed. 1972: 240)."

R. Klein, 2 Chronicles, 45 n. 4.

Raymond Dillard, 2 Chronicles, 27 similarly postulates a possible allusion to Gen 22:8, 14.

So also J. Myers, II Chronicles, 16–17.

I. Kalimi, "Land," 346.

Moriah and the ‘Aqedah developed a connection with the Passover in rabbinic teachings. J. Levenson, Death, 174 states: "In the one word 'Moriah' in 2 Chr 3:1 lies the germ of the rabbinic notion that the aqedah is the origin of the daily lamb (tĕmîdîm) and, less directly but more portentously, of the passover sacrifice as well." See also L. Kundert, Opferung, 1:245.