Proteus Emerges in the Early Church (Part II)

An Historiographical and Stylistic Examination of Three Pauline Speeches in Acts | Situating Luke-Acts in Ancient Historiography

This is a continuation of a piece on Luke-Acts and Historiography. If you have not read the first entry, then you might be a bit lost picking up in the middle of the study.

Greco-Roman Historiography & the Acts of the Apostles

Historiography has evolved over the millennia in methodology and perception. Already, we have conducted a cursory perusal of some modern approaches, but now let us transition to a more pertinent field of research pertaining to Luke-Acts: ancient methods of historiography. The way in which the ancients conducted their historical reports differ from our own, and thus they must be assessed differently.

One should bear in mind that this is not precisely true. We have retained some modes of conveying history through mediums other than scholarship. Like Homer's Iliad, we also retell history through artistic expression. One could also consider the comedy, Clouds, by Aristophanes as a legitimate and historical portrayal of Socrates, albeit through satirical/theatrical means.

I do not mean to insinuate that the ancients perceived Homer’s account as merely artistic, though. Typically, cultures express their earliest writings through poetry and verse, and mythology quite commonly influences this presentation. As for our modern context, the film Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, for example, does something similar. Much of the humor is derived from historical fact; many of the jokes are lost if the viewer is not familiar with the historical events/people referenced and the contemporary zeitgeist of the movie.

This project cannot hope to plumb the plethora of avenues necessary for understanding Luke-Acts’ integrity with respect to ancient historiography.1 With that said, I wish to focus on two main aspects to uphold the “genuineness” of Luke’s history. The first will discuss the Gospel’s introduction in comparison with historical accounts from antiquity.2 Since Luke claims in Acts that this is the second volume of his work, I presume that the introduction to the Gospel still holds for act two.

The second segment concerns the art of recording speeches in antiquity, but I will tackle this in the third entry of the series. Briefly, this will include analyzing three main speeches in Luke-Acts, concentrating on Paul. This study reveals that Luke upheld Paul's sentiment in 1 Corinthians 9, when he stylistically displayed Paul employing varying rhetorical techniques as he speaks before Jews (13:13–52), argues amongst Gentiles (17:16–34), and bids farewell to a Christian community (20:17–38).3

Now, let us examine various genres of recording “history” in antiquity and how they relate to Luke-Acts.

The Interminable Literature from Antiquity and Luke's Prologue

“Oh dear, oh dear! Lord Zeus, what a stretch of nighttime! Interminable. Will it never be day?” (Aristophanes, Nub. 1–3). These words from Aristophanes’s ill-received comedy are quite portentous for our current plight. The amount of Greco-Roman literature appears insurmountable, and when one considers the plethora of Jewish sources at our disposal, the task becomes herculean. Be that as it may, we must explore key works in order to establish connections with Luke-Acts so as to reveal in part the genre(s)4 in which it might belong—is Luke limited only to the genre of history?

The reasons for this include, (1) knowing the genre of the work is imperative for a proper assessment of the speeches; (2) the introduction of this work claims historical accuracy, so we must explore how it compares with analogous literature;5 and (3) the way in which historical fact is conveyed differs from genre to genre. With that said, we will explore briefly plays,6 geographies, and lastly histories.7

Socrates in the Clouds: Historical Plausibility in Comedy

The Gospel nor Acts are a form of tragedy or comedy; we can state that with certainty. The structure is not reminiscent of a Greco-roman play, nor are there any choruses spread intermittently throughout. The reason for beginning with such a genre entails establishing historical reliability within a composition. Historical Socrates research is not as pronounced as that of biblical studies’ pursuit of the historical Jesus, but a similar dilemma exists since neither teacher—as far as we know—composed any literature to be passed on to their pupils/disciples.

In Aristophanes’s Clouds,—a satire of Socrates and his students—we find a caricature of Socrates that could be a fair representation of the historical figure, but discrepancies arise when we explore Plato’s Symposium.8 In the Symposium, Agathon invites both Socrates and Aristophanes to his home for a drinking party, but there is no animosity depicted in the narrative. Kenneth Dover argues,

Aristophanes, as author of Clouds, may possibly have been so hostile to Socrates that even the most self-confident of hosts would have thought twice about inviting them to the same party; but it would be going far beyond the evidence to say that Agathon did not invite them.9

This dilemma is akin to that of which Haenchen wrote concerning the historical authenticity of Acts. He contended that the representations of the apostles must be held in question since, “Peter and Paul are figures drawn from the same model: they embody the apostolic ideal seen through the eyes of Luke’s age”; additionally, Conzelmann posited, “Where the book of Acts and Galatians diverge from each other, Galatians always deserves to be preferred. Luke apparently did not possess a coherent source on the council but attempted to form a picture from scattered reports.”10

The difference, though, is that Paul actually left us literature to consult, and so we have a direct self-understanding of the person in question. Regardless, classical scholars dispute the historical reliability of the Symposium,11 but there appears to be possible truths in the comedy:12

Aristophanes’ portrait of Socrates as the arch-sophist, atheist, and corrupter of the young is at variance with the portraits later drawn by philosophical writers like Plato and Xenophon; in Apology, Plato tries to show the inaccuracy and unfairness of the popular image of Socrates, fueled by comedies like Clouds, that played what he considered the decisive role in Socrates’ condemnation on capital charges in 399 (Ap. 18b–c).13

Even though the play is fictitious, there are facts that undergird the satire. If this were not the case, the apologies for Socrates would not have arisen, and he would not have been put to death.14 Thus, similar to Luke-Acts, it is the message that is being presented that is of utmost importance, not the details of historicity. Even though the prologues of Luke and Acts—as we will explore—purport efforts in generating a historically reliable narrative, the purpose of the Doppelwerk is what controlled the author’s pen.

Mountains and Whale-Roads: The Intersection of Geography and History

The genre of geography is a fitting middle discussion to have because it points forward to the focus of this analysis. As Loveday Alexander wrote, “Geography for the Greeks was a branch of historia at least as old as historiography, and many writers followed Herodotus in combining the two.”15 The truth of this statement becomes most apparent after exploring a number of different writings that fall into a number of genres, yet still contain geographic details. Plutarch exemplifies this when he wrote,

Just as geographers, O Socius Senecio,16 crowd on to the outer edges of their maps the parts of the earth which elude their knowledge, with explanatory notes that “What lies beyond is sandy desert without water and full of wild beasts,” or “blind marsh,” or “Scythian cold,” or “frozen sea,” so in the writing of my Parallel Lives, now that I have traversed those periods of time which are accessible to probable reasoning and which afford basis for a history dealing with facts, I might well say of the earlier periods: “What lies beyond is full of marvels and unreality, a land of poets and fabulists, of doubt and obscurity.” (Theseus 1.1)

This first example reveals that strict genres are not a surety in ancient compositions. Here, we have a blending of biography and history, but Plutarch parallels his work with that of a geographer. He even concedes that his work is rather akin to that of geography, for one must fabricate information concerning areas with which one is quite unfamiliar. His recognition of the difficulty of retelling events that are far removed is telling—even the ancients were aware of the issues.

We will soon explore the varied forms of introductions found in ancient histories, but let us now glimpse at one in particular that can be of some aid to our current investigation. Appian began his history as follows,

Intending to write the history of the Romans, I have deemed it necessary to begin with the boundaries of the nations under their sway (Roman History 1.1).

Within this quotation is held numerous details of interest, which include, self-recognition, intent for writing, and a simple quip concerning the parameters of his introduction. As the history unfolds, Appian expounds on the geographical regions that pertain to his history. Thus, we can see that geography is not so divorced from historiography.

The Periplus of Hanno is yet another specimen that ought to be considered in our venture.17 The author of the travel log narrates the route the crew sailed, while also commenting on specific details of interest. This piece focuses largely on the geography and waterway, but it is sprinkled with what one might consider historical details and descriptions. The work contains a depiction of a volcano erupting, and also it expounds on the hairy women who resemble gorillas; the author even expresses the fear his comrades exuded when they encountered people clanging cymbals, playing pipes, and hammering on drums one night. This voyage is vaguely reminiscent of Paul’s missionary journeys detailed in Acts.

To Compose an Orderly Account: Ancient Introductions to History

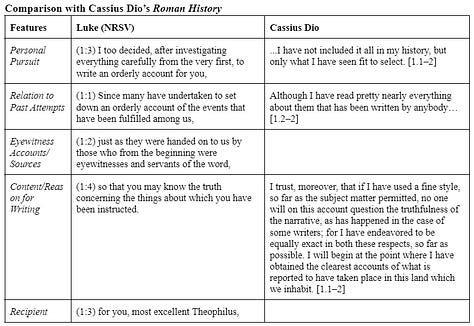

To conclude this segment, let us examine the parallels between the introductions of a few works from antiquity and Luke. Every historical account from the Greco-Roman world is not identical,18 obviously, but there are some instances in which they share characteristics with Luke.19

As I explored these different works from the Greco-Roman world, four commonalities arose:

Personal recognition/pursuit

relation to past attempts

eyewitnesses/sources20

content/reason for writing21

Luke-Acts specifically addresses a recipient, but Plutarch (cited above) is the only author I have found to contain a parallel connection. Provided below are graphs of these characteristics that I discovered in Luke in comparison with five different authors from antiquity to illustrate these correspondences:22

In her work The Preface to Luke’s Gospel, Loveday Alexander chose to emphasize “the scientific tradition” or “technical prose” with reference to Luke-Acts instead of ancient historiography.23 I do not wish to engage with her work fully here due to space, but I do not think the dichotomy of genres should be over-emphasized as scholars have generally tended to do in this debate.24

Rather, I believe the two are not in tension because the narrative history of Luke-Acts fits into multiple classifications.25 As such, the introduction to Xenophon’s Apology contains an introduction rather similar to the historiographical introductions just examined:26

Thus, we ought to conclude that these characteristics are not particular to historiographical writings. Instead, the data suggests that there is some overlap between “genres.” Xenophon’s Apology is not recorded history proper, but it appears that he wished to express the historical plausibility based upon his source, Hermogenes. Hence, based on the research, we can conjecture that historical methodology could be applied to categorically separate pieces of literature.27

Polybius will close our discussion since he expounds on a number of themes that point forward in our study and backwards.28 Polybius (Hist. 12.25b) wrote,

For the mere statement of a fact may interest us but is of no benefit to us: but when we add the cause of it, study of history becomes fruitful.

Polybius—as Schnelle and Schröter argued in the first part of this series—intimates that the mere telling of facts is borderline pointless for the audience; unless the historian can make the information applicable, the recitation of events has little to no meaning.

In turn, Timaeus is critiqued throughout this section of book twelve for his lack of precision and inability to properly report history. As such, Polybius (Hist. 12.25e) described the art of historiography with three characteristics,

In the same fashion systematic history too consists of three parts, the first being the industrious study of memoir and other documents and a comparison of their contents, the second the survey of cities, places, rivers, lakes, and in general all the peculiar features of land and sea and the distances of one place from another, and the third being the review of political events...

Seemingly, Luke strove to live by these three points, or, at the very least, he employed them in order to situate his narrative as a proper historical account. First and foremost, I am not suggesting that Luke consciously knew Polybius’s standards of historical methodology and then implemented them into his Doppelwerk. That would be preposterous. I am attempting to show that Luke’s narrative of the Church parallels ancient histories with respect to a profusion of aspects. If he had desired to uphold Polybian standards of history writing, he would have followed his instructions (Hist. 2.56.10–12):

A historical author should not try to thrill his readers by such exaggerated pictures, nor should he, like a tragic poet, try to imagine the probably utterances of his characters or reckon up all the consequences probably incidental to the occurrences with which he deals, but simple record what really happened and what really was said, however commonplace.

That said, the three traits can all be found within the narrative:

Luke’s History and Polybius’s Methodology

The study and comparison of sources: Although we possess none of Luke’s sources for Acts, critical scholarship holds that Luke contained numerous sources for his Gospel;29 see Luke 1:2; St. Ambrose, Exp. Luc., 1.4, 7; Eusebius, Hist. eccl. 3.4

Survey of geography: Although not extremely expansive, the missionary journeys certainly exemplify these features:30 Acts 13:4ff., 13ff; 14:1ff., 8, 21; 16:1, 6ff., 11ff.; 17:1; 19:1; 20:1, 13ff.; 21:1ff.

Knowledge of political events: This is revealed in the historical snippets placed intermittently in the narrative: Luke 1:5; 2:1; 22:1ff.; Acts 12:1ff, 20ff.; 15:22ff.

Even though all of these characteristics can be found within Acts, does this signify that the book is historically accurate? Certainly not; there are other factors that must be weighed in order to determine its veracity.31 With that said, though, Luke surely intended his work to be read as a historical narrative similar to the other such recordings explored above.

Conclusion

The purpose of this second entry is to establish the norms of ancient historiography, at least briefly, as well as establish the genre of Luke’s Doppelwerk. Genre is a critical aspect to realize since it dictates how someone should read the work. If you read a satirical piece as historical, you have missed the author’s point. As for Luke-Acts, I have been referencing it as a narrative history, when it is probably more accurate to call it a theological narrative history because that is the foundation of the account.

I have explored above multiple genres to show that blending can occur when attempting to establish a work’s genre. In Luke-Acts, I find the primary goal was to convey a theological point: Who Jesus was and how the Church began and continued on after his death, resurrection, and ascension. This was accomplished through a narrative, which was based on detailing historical accounts. The foundational genre of Luke-Acts is history, but I use narrative as a descriptor because Luke was writing a story. Be that as it may, the historiographical aspect of the Dopplewerk cannot be minimized since Luke clearly saw accuracy as a critical component of his composition.

Be that as it may, a difficulty of ancient history is discerning how informed the general populace would be. We know the literacy rate was abysmal, so we can only assume that the dearth of knowledge about world history would be near equivalent. People were more likely to know the events that had transpired in their town or local region,—this is true even today, and we have the luxury of broadcast television and the internet—but how many citizens of the Roman empire would know the names of and the events that led to the year of the four emperors (AD 69)—the year prior to the destruction of the Second Temple, AD 70), for instance?

This may seem like a tangent, but if a citizen is unable to read, that person is reliant on someone else to become informed concerning events outside of their bubble. As such, the transmission of information is more difficult because it is contingent upon word-of-mouth rather than reading documents. With the fragility of memory, this could lead to a fragmented recollection of one’s own communal history, and without the foundation of a written history, this further complicates record keeping.

Now, we know in early Christianity Paul’s letters were circulated and read,32

|1| Take up the epistle of the blessed Paul the apostle. |2| What did he first write to you in the beginning of the gospel? |3| Truly he wrote to you in the Spirit about himself and Cephas and Apollos, because even then you had split into factions. (1 Clem 47.1–3)

For they say, “His letters are weighty and strong, but his bodily presence is weak, and his speech of no account.” (2 Cor 2:10)

...not to be quickly shaken in mind or excited, either by spirit or by word, or by letter purporting to be from us, to the effect that the day of the Lord has come. (2 Thess 2:2)

So, at least in major locales,—e.g., Rome—you were more likely to have someone educated with the capacity to read. What about in the outskirts of Judea? The likelihood of having a literate person was far less, so the recording of their local history was probably reliant on human memory rather than on written records.

When composing a history, this could prove problematic. Poor memory coupled with the lack of written records would work adversely in the discovery of historical fact. As such, when Luke was composing his narrative history of the birth of the Church, reliable sources were certainly hard to come by. This is why it must be remembered as we progress through the final stage of this study that the impetus for Luke writing is far more important than the potential discrepancies or the possible hiccups in the historical account.

Luke tells the story of the christ and his purpose for coming, and then he generates a second volume to detail the creation of the Church, highlighting its star apostle: Paul. The thematic cohesion is significant, and it is the driving force behind Luke’s pen. This must be kept in mind when we explore the speeches as an example of the narrative components of Luke’s history. It is the message that is critical, not the exactitude of what was written down.

This is not to say that the account is wholly unreliable. But remember, there were no recording devices in antiquity. As a preview, it should not come to the reader’s surprise that the speeches in Acts are not verbatim records of what was said. That would, honestly, be rather ridiculous. It would require a record of what was written down precisely as the speech was given.

Ultimately, this three part work is meant to shed light on the difficulties of ancient historiography, while simultaneously placing the emphasis on what is most important concerning history: the message. Luke desired to promote a unified Church amongst Jews and Greeks in Acts, and this should be kept in mind as one of the driving themes of the theological narrative history. His Ecclesiogony is meant to cross the divide between Jew and Greek in order to establish a foundation where two seemingly disparate cultures could coexist within the same religious framework.

If you wish to continue reading about Luke, Paul, Acts, and the historiography of the Early Church, would you kindly subscribe?

For this, peruse the expansive introduction of C. Keener. Acts (Baker, 2012).

The project of this size cannot hope to explore the amount of literature that Loveday Alexander explores in The Preface to Luke's Gospel (Cambridge, 1993) and Acts in its Ancient Literary Context (T&T Clark, 2005).

Obviously, this will be a limited discussion due to space. The focus will not be centered on each speech individually, but, rather, on how the three can be seen in contradistinction to one another. This is beneficial because one begins to perceive that Luke wished to uphold the memory of Paul's rhetorical styles.

G. Parsenios, Departure and Consolation (Brill, 2005) states concerning the Gospel of John, “Following John’s typical patterns, the Farewell Discourses are not faithful to any single genre, even the testament. The Gospel’s purpose is to narrate the story and the significance of Jesus. To do this, it makes use of several different literary forms depicting death and responses to death and departure.” I suggest we follow this trend in Acts because the composition appears to take the form of multiple categories. As we shall see regarding the speeches, this trend becomes most explicit.

Consider this harsh expression from Polybius’s own pen (Hist. 12.25a): “When we find one or two false statements in a book and they prove to be deliberate ones, it is evident that not a word written by such an author is any longer certain and reliable.”

This will be a more specific comparison than the others. This discussion will focus on the presentation of Socrates in Clouds and the Symposium to illustrate that a fictitious account is not void of a historical foundation.

The corpus of Greco-Roman literature is expansive and the number of genres profuse; therefore, the limitations of this paper restrict this analysis to only these few mentioned. I would also like to explore epic poetry, for some historicity lurks behind these tales; consider Lucan’s Civil War (1.1–5).

In fact, after Socrates’s trial and death, a new literary genre emerged that attempted to expound on the life and philosophical teachings of Socrates (the Sokratikoi logoi). These ancient authors attempted to—according to John Cooper Reason and Emotion (Princeton, 1999), 3—“present Socratic-style dialogues very much of his own construction. Not only Plato and Xenophon wrote such dialogues, but also perhaps among others, Aeschines of Sphettos and the philosophers Antisthenes, Euclides, and Phaedo, none of whose works have survived apart from isolated quotations and short excerpts.” The question remains, though, are these accounts historically reliable?

K. Dover, Symposium (Cambridge, 1980), 9.

Haenchen, The Acts of the Apostles, 80. Conzelmann, History of Primitive Christianity, 85.

During Alcibiates’s drunken banter, he lauds Socrates’ courage while they were in the military together, recounting how valorous he was by saving his life. Other Platonic dialogues mention Socrates’ military service, so there are historical nuggets within the discourse.

That is not to imply that the Symposium is entirely fictitious with no underlying veracity like Clouds. Be that as it may, Richard Hunter, Plato's Symposium (Oxford, 2004), 3 states, “Plato's Symposium is the account of a (presumably fictional) gathering in the house of the Athenian tragic poet Agathon…” There are problems with Plato’s socratic dialogues as Gregory Vlastos, Socrates (Cornell, 1991), 46 shows,

In different segments of Plato’s corpus two philosophers bear that name. The individual remains the same. But in different sets of dialogues he pursues philosophies so different that they could not have been depicted as cohabiting the same brain throughout unless it has been the brain of a schizophrenic. They are so diverse in content and method that they contrast as sharply with one another as with any third philosophy you care to mention, beginning with Aristotle’s.

So, also, he believes that there are two different portrayals of Socrates in Plato’s corpus alone: the more historic Socrates as a moral philosopher from the earlier works, and then the Socrates of the later dialogues who serves as a mouthpiece for Plato’s own thought and philosophy.

J. Henderson, Aristophanes vol. 2 LCL (Harvard, 1998), 5.

Works such as Plato’s Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, and Phaedo would not have made sense if Socrates had not been imprisoned and sentenced to death.

Alexander, Acts in its Ancient Literary Context, 147.

Note that Plutarch has specifically addressed a recipient.

Other such accounts exist from antiquity. The texts have been compiled in C. Müller, (ed.) Geographi Graeci Minores I and II (Didot, 1855, 1861).

There were different views on proper methodology in antiquity. Polybius’s History is aligned with an exceedingly strict view of recording, but Cicero (Laws 1.5) defines history as “a branch of study which is predominantly the concern of the orator.”

“Annals” were different from “history,” as discussed by Aulus Gellius, Noct. att., 5.18.8.

For others who mark the importance of eye-witness accounts, see Hdt. 2.19, 44, 75, 113, 118, 6.19 and Tacitus Ann., 3.16, 15.53. For an account of one who is concerned with reporting different points of view, see Suetonius, Claud., 1.

There are a number of other parallels that I have not included in the charts. Some authors speak of truth, historical truth, orderly accounts, etc. Thus, these few examples show that Luke at least partially falls in line with other historians of the era. Also, historical introductions contain characteristics that are not present in Luke, but we shall only focus on those that are shared between both.

Livy (History of Rome, 1–12) in his prologue also contains a number of these connections. I have refrained from listing the comparison for the sake of space. Also, his prologue is quite long, so the analysis would be more difficult to assess.

See the introduction to her work Acts in its Ancient Literary Context for a response to many critiques of her aforementioned book. I do not wish to combat her thesis, but I want to emphasize the relationship Luke has with ancient historiography. She does not divorce Luke from history; Alexander shifts the emphasis.

See D. Aune, “Luke 1:1–4: Historical or Scientific Prooimion?,” in Pal, Luke, and the Graeco-Roman World (Sheffield, 2003), 138–148.

Stanley Porter, “Thucydides 1.22.1 and Speeches in Acts: Is There a Thucydidean View?" NT 32 (1990): 125 supports my claim. In his critique of Alexander’s focus on scientific prose, he states,

Alexander must admit that although the prefaces in Luke/Acts share many characteristics with the prefaces of scientific prose (e.g. address in second person), there are also several differences, e.g. some scientific prefaces are much longer than Luke’s (one of Archimedes’s letters has an eight page preface; some scientific works have no preface), suggesting that a continuum rather than a simple opposition between literary and scientific prose is necessary.

This is precisely my point, that we should be reticent to relegate Luke to a categorical distinction that his work may not be. Cannot his Doppelwerk fit multiple characteristics of multiple genres?

There are a number of other dialogues with parallel introductions, but they do not express as many characteristics as Xenophon’s Apology. Consult Phaedo 57A and Symposium 172A. Ion, Shorter Hippias, Gorgias, Phaedrus, and Euthyphro, all begin with the dialogue between Socrates and an interlocutor. Thus, as far as socratic dialogues are concerned, it is out of the norm to possess all of these characteristics. Xenophon’s style differs from that of Plato’s wherein he makes the introductions from the first person perspective. For example, he proposes an inquiry in Memorabilia, he is reminiscent in Oeconomicus and Symposium.

This becomes problematic, though. At what point do we concede that part of the narrative is fictitious? How do we know what is historically rooted and what is mere fabrication? I do not wish to argue that Luke’s Doppelwerk is strictly a historical account akin to Thucydides or Tacitus, but, perhaps, similar to Herodotus—the blending of myth and research; his relation to the gods and history is intriguing. Luke himself emerges as a Proteus for he also adapts his narrative to include that which is most beneficial for his purpose. Thus, as I detailed previously with respect to Tweed, we see that the genres of ancient literature may be more fluid than at first presumed. The character of Luke differs largely from Acts, but I believe that Luke is able to blend characteristics as we have just seen Xenophon do.

Polybius’s Histories begins with a lengthy diatribe concerning historical methodology, those who have previously conducted a similar study, and the importance of his own venture (See 1.1, 14; 12.12.4; 16.14–16). Albeit these fit into the categorical distinctions I provided above, Polybius’s rant exceeds that of Luke’s one verse quip.

This is quite dependent on one’s view of the Synoptic Problem. Luke could have possessed, (1) Mark, Matthew; (2) Mark, Q, Special Luke; (3) Any combination of the aforementioned and oral tradition. “Special Luke” is such a nebulous designation that it is impossible to ascertain what exactly this included. Regardless, no scholar believes Luke was left without any sources. Acts remains more contentious since we have no other works to compare with it.

I believe the “we” passages should be included in this discussion. Even if one were to believe they are fabrications, it at least indicates that Luke wished to portray the events as first-hand, eyewitness testimonies. There are some who argue that these might be other sources that Luke has used from a ship’s log. For a detailed survey on these passages in Acts, see chapters one and two in Stanley Porter, Paul in Acts (Hendrickson, 2001). These passages could also play into the before mentioned category.

As M. Finley Ancient History (Redwood Burn Ltd., 1968), 9 argued, “ancient writers, like historians ever since, could not tolerate a void, and they filled it in one way or another, ultimately by pure invention.” Such sentiments lead many to distrust the account, but we must temper such claims with a certain level of trust.

See L. Mowry, “The Early Circulation of Paul’s Letters” JBL 63.2 (1944): 73–86.