Nota Bene: If you have not read the first entry in the series, it might be helpful for the context of this post and the one that follows. It can be found here.

In the Weeds of Textual Criticism

Determining the authenticity of a disputed word, verse, or entire passage is tricky.1 Oftentimes, there is not a smoking gun, so the textual critic has to make a decision based on what we have in the manuscript (ms) tradition, along with a number of guidelines (see entry #3). As for the wealth of New Testament evidence, we have extensively more documents to compare and contrast than most any other work from antiquity; there are 5,338 Greek mss, hundreds of copies of ancient translations (e.g., Syriac, Coptic, etc.), 8,000+ copies of the Latin Vulgate, and a surfeit of quotations from the Church Fathers and Mothers.2 Our earliest, substantial surviving ms dates somewhere around AD 200,—there are earlier surviving partial documents—but the large majority of our best evidence is from the fourth century and beyond.3 This abundance is both a blessing and a curse, for it improves our chances of discerning what the original NT contained, but it also leads to more contention due to the plethora of variants. The primary goal of this series is to provide you with the basics of textual criticism so that you may understand why some verses are dropped and other narratives are bracketed in your modern translations of the New Testament.

For Epp and Fee,4 there are at least 3 ways in which textual criticism is helpful:

To discern the original words of the author, through examining the discrepancies

To produce an accurate translation, from this discernment

To see a scribe’s or a church’s theological interests and possible historical exegesis, by examining the variations5

Although the task of the textual critic is onerous, the product is significant since it assists us in better comprehending what the original author intended for us to read, which ultimately leads us to a greater understanding of Scripture.6 First, we will explore the manuscript families and the types of documents we possess for analysis, then, in the third entry, we will look at the steps that are taken for determining originality, which will conclude with an assessment of Matt 17:21.

Document Types

Since the New Testament was written well before the printing press, disseminating the documents meant copying the books and letters by hand. The more times the texts were reproduced, more errors slipped into the ms history.7 Afterall, it was inevitable that scribes would make mistakes, whether intentional or not, and this explains why no two mss are identical. One can only imagine the tedium of copying the entire NT by hand, and we commonly do not appreciate our ability to read and write. These were skills few in the ancient world possessed. The exhaustion this process caused is evidenced by scribal notes found at the end of manuscripts, for example,

Mercy to the one who wrote it, Lord; wisdom to the one who reads it; grace to the one who hears it; salvation to the one who copied it. Amen. ~Prayer at the close of a Psalter, copied AD862

The end of the book; thanks be to God!8

You may think the following material is unnecessary to comprehend when discussing textual criticism. Afterall, what does handwriting and document types have to do with analyzing the authenticity of a form, word, phrase, or pericope? To put it simply, one must know the nomenclature and symbols used in the textual apparatus to follow an argument, and these characters are based on categories derived from these aspects. Additionally, as Wescott and Hort writes, “knowledge of documents should precede final judgement [sic] upon readings.”9

Materials of Ancient Documents

The material used for each reproduction was not identical; the possible mediums include clay tablets, stone, bone, wood, leather, various metals, ostraca (pot sherds), papyrus, and parchment (vellum). With the literacy rate being terrible and the aforementioned materials being in short supply,—not to mention expensive—we are exceedingly fortunate to have so many witnesses at our disposal.

The most significant of these materials for the NT are those written upon papyrus or parchment because the vast majority of literary works were composed, transcribed, and written on scrolls in the first century Greco-Roman world. Scrolls, though, were not ideal for reading documents, especially ones as long as Luke or Acts—the two longest in the NT—because the reader was required to employ the use of both hands: One hand was needed to unroll the scroll while the other simultaneously rolled up what had just been read.

Reading was tedious. Early in the second century was the advent of the codex,—leaf-form of a book—and it understandably became extensively used within the Church.10 That said, all the extant copies of the NT are codices; no scrolls have been discovered.11

Handwriting & Types of Manuscripts

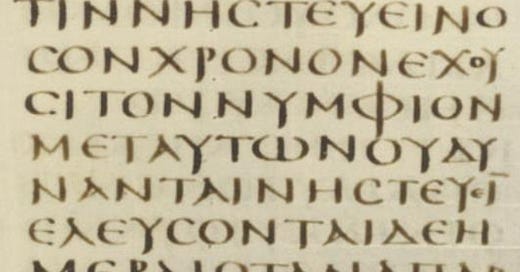

At the time when these mss were written and copied, there were two forms of Greek handwriting: uncials and minuscules. Literary works were written in a formal way which would have been in the uncial form; Metzger states, “This ‘book hand’ was characterized by more deliberate and carefully executed letters, each one separate from the others.”12 There are no spaces between words,—called scriptuo continua—nor are there chapter and verse numbers or section titles—all of these were later inventions in the development of copying the Bible.

Around the 9c., reforms in handwriting for copying occurred because uncial tomes were becoming exceptionally thick. This led to the use of minuscules which was a smaller script. This “running” hand could be written quickly, and it was a sort of cursive form of Greek. Initially, the minuscule form was used for non-literary works such as letters, accounts, receipts, petitions, deeds, and other documents. The number of minuscules we possess out number uncials by about ten to one.13

Apart from handwriting, there are four different groups of Greek mss: Papyri, Uncials, Minuscules, and Lectionaries.

Papyri

The papyri consists of some of the earliest witnesses. These documents were written on papyrus leaves in the uncial script. There is no separation between the different words; there is little to no punctuation in the text. These documents are identified by a Gothic or Old English letter “P” (𝔓 or þ) followed by a superscript number, e.g., 𝔓46.

Few copies of these have survived, but fragments or large portions of about 124 different papyri still exist,14 ranging from AD 125 to the 8c., though the majority belong to the third and fourth centuries.

Uncials

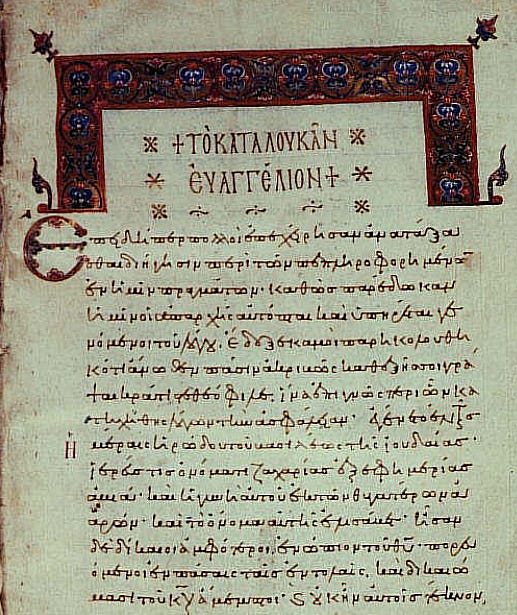

Beginning in the 4c., uncials began to be produced on parchment (vellum), replacing papyrus as the primary medium for writing. These documents were prepared animal skins, which made them more durable and larger in size, and they were used for most literature from the 6c. to the 14c.

Initially, uncials were denoted by capital letters of the Greek and Latin alphabet and by one Hebrew character, the ‘aleph (א). This became problematic with the discovery of more uncials since the number exceeded that of the number of Greek, Latin, and Hebrew characters. Now, each uncial manuscript has been assigned an Arabic numeral preceded by a zero (0). There are over 300 known uncials, but only one contains the entire NT: Codex Sinaiticus (01, א). Codex Vaticanus (02, B) has almost the entire NT except for 1 Timothy to Philemon and Hebrews 9:14 through Revelation.15

Though these documents are signified by 0 plus an Arabic numeral, the first 45 are also denoted by their original symbols. Some of the most significant include:

Minuscules

Beginning in the 9c., minuscules rose in popularity. The script—as noted above—was the “running” hand or cursive script that had replaced the uncial style. The advantages of these texts were both the speed at which they could be produced, and the cost was lower to make. This group makes up the vast majority of mss available to us today, and they are noted simply by Arabic numerals, 1 to 2795.

Lectionaries

The fourth and final group of Greek mss are called Lectionaries. This is the second largest group of documents,—over 2400 exist16—and they are unique compared to the other three groups. Lectionaries do not contain the scriptures in canonical sequence because they are set in the order of daily and weekly lessons from the Gospels and epistles. These mss are designated by a cursive l (ℓ) followed by a superscript Arabic number. Additionally, there is further notation for lectionaries: the ℓ alone indicates a Gospel; ℓa signifies the lectionary contains Acts and the Epistles; and ℓ+a shows all three are contained therein: the Gospels, Acts, and the Epistles—no Greek lectionary possesses lessons from Revelation.17

MSS in Other Languages

To add to this wealth of Greek mss, there are other witnesses to the early NT text in different languages. From the 2c., translations were done in Latin, Syriac (the Pesshita), and Coptic (Egyptian); then in the following centuries as the church expanded, the NT was translated into Gothic, Armenian, Georgian, Ge’ez (Ethiopic), Slavonic, and Arabic.

These languages, though, cannot always express grammatically the Greek, so a lot of corruption of the original text arose from translations. Even so, these texts are still significant for helping us discover the original text and understand the history of transmission.18

Patristic Literature

The final group of mss are quotations of Scripture by the Church Fathers. Patristic citations are complicated in aiding our endeavors due to a number of factors. Primarily, the Fathers often cited from memory, so it is not always clear whether the quotation is authentic or corrupted. A second complication,—similar to the OT and NT—we have no original manuscript of the Church Fathers. These are all copies, and they are usually later copies, which have potentially suffered extensive corruption. The main significance of analyzing these texts is to trace the history of textual transmission, similar to the NT translations.

Textual Families

As previously stated, the vast amount of manuscripts at our disposal is both a blessing and a curse: A blessing because, amongst the plethora of witnesses, we in all likelihood have the original text hidden amongst all the variants; a curse because we have to sift through an enormous pile of refuse, hoping to find that original text. In order to explicate how these manuscripts are categorized, some historical context must be established.

In the nascent church, major cities—Alexandria, Antioch, Rome, etc.—would have “local texts,” which were their unique copies of the New Testament. These texts, in turn, would be copied repeatedly over centuries, resulting in the proliferation of errors,—and their unfortunate preservation—which were unique to these individual communities. Some of these mistakes would become particular to these metropolitan local texts because, for instance, an error would arise early on that would then be copied with each iteration, preserved in the manuscript history for those churches.

Unless one were to find a ms from that ecclesial body—assuming it survived—that was composed prior to the origin of the mistake, the authentic text would be lost to history in that geographic region—at least potentially. So, with each new copy that was produced, the number of special readings could grow because no copyist was ever perfect, and these gaffes would be unique for each of these local ecclesial bodies. Because of this, we can trace the manuscript history based on certain characteristics and group them accordingly.

There is an assumption here: these texts always stayed at home and never migrated to other major city-churches. Manuscripts would be shared between these communities, but it was relatively rare since travel and the transportation of documents was more difficult than today. As such, these blended texts were not entirely common, and there are distinctive, identifiable tendencies for the major ms groups that help us in categorization.19

Since no two manuscripts are identical, this becomes problematic when analyzing the various texts. Fortunately, many of the mss resemble one another and are able to be grouped into families of texts, also called text-types. These manuscripts are classified based on two primary aspects: (1) The percentage of agreement with one another; (2) how much they agree in their variant readings that are unique to them. The three families are (1) Alexandrian, (2) Western, and (3) Byzantine—the majority and what was considered authoritative. With the advent of Gutenberg’s printing press, the Byzantine text was solidified as the standard.

Conclusion

In the final entry on textual criticism, we will explore the methodology for analyzing mss and variants to determine what most probably was original to the NT. I will conclude with a practical application of the process, explaining why Matt 17:21 has been determined to be inauthentic.

If you want to learn more about textual criticism and the New Testament, would you kindly subscribe?

For more on textual criticism, consult this short bibliography that follows. These texts influenced and informed this entry, and I will not be providing citations for the summary of general information.

N. Birdsall, “The Recent History of New Testament Textual Criticism (from Westcott and Hort, 1881, to present)” in Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt, eds. H. Temporini and W. Haase (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1992), 99–197.

B. Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture (New York: Oxford, 1993).

B. Ehrman and M. Holmes, eds., The Text of the New Testament in Contemporary Research (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1995).

R. Brown, An Introduction to the New Testament (New Haven: Yale, 1997), 48–54.

B. Ehrman and M. Holmes, The Text of the New Testament in Contemporary Research 2nd rev. ed. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1995).

J. Elliott and I. Moir, Manuscripts and the Text of the New Testament (Edinburgh: Clark, 1995).

E. Epp & G. Fee, The Studies in the Theory and Method of New Testament Textual Criticism (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1993).

M. Holmes, “Reconstructing the Text of the New Testament” in The Blackwell Companion to the New Testament ed. D. Aune (Oxford: Blackwell, 2010), 77–89.

M. Holmes, “Textual Criticism” in Interpreting the New Testament eds. D. Black and D. Dockery (Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 2001), 4–73.

B. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, 2nd ed. (New York: United Bible Societies, 1994).

B. Metzger, The Text of the New Testament 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford, 1968).—there is a 3rd ed.

B. Metzger, Manuscripts of the Greek Bible (New York: Oxford, 1981).

B. Westcott and F. Hort, The New Testament in the Original Greek (Cambridge Macmillan, 1881; 2nd ed. 1896).

On these specific numbers, see Epp & Fee, Studies, 3.

C. Tuckett, Reading the New Testament (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1987), 21.

Epp & Fee, Studies, 3.

Some variants are accidental, yet some are intentional. The history of these texts tells us more than just what the base text should be; when a scribe intentionally alters the text, they did so for a reason.

Many textual variants are not all that critical, but some can greatly impact how a verse or paragraph could be read. In fact, there are whole verses, paragraphs, and narratives that may not be authentic, e.g., the ending of Mark and the Woman Caught in Adultery (John 7:53–8:11). It is the work of textual critics that help us determine the original authorial intent.

B. Ehrman, Misquoting Jesus (New York: Harper Collins, 2005), 46 writes, “Anyone reading a book in antiquity could never be completely sure that he or she was reading what the author had written. The words could have been altered. In fact, they probably had been, if only just a little.”

From Metzger, Text, 18.

Westcott and Hort, New Testament (1881), 31.

See Metzger, Text, 3–6.

Epp and Fee, Studies, 4.

Metzger, Text, 9.

Metzger, Text, 12.

See Holmes, “Reconstructing,” 79.

Epp & Fee, Studies, 5.

Holmes, “Reconstructing,” 80.

Metzger, Text, 33.

As M. Holmes, “Reconstructing,” 80 notes, “Because the roots of some of these early versions pre-date the vast majority of the Greek MSS, they are valuable historical witnesses to the transmission of the New Testament text, particularly regarding the form of the text in various regions or provinces.”

Also, the arrogance of humans likely would have played a factor. If ecclesial community A has one reading, and ecclesial community B has a variant, each one would probably assume the other is wrong.