The Johannine ‘Aqedah

A Study on the Development of Genesis 22 within Judaism and the Nascent Church | Part 2: Jesus as the New Isaac

It is critical that you have read at least the introduction to the first part of this series so that you are familiar with the typology that I will be evaluating in John, that is, how Jesus is the New Isaac.

As a refresher, the characteristics of the Isaac typology include:

A father sacrificing an only (יחיד, ἀγαπητός, µονογενής) son,

Isaac being a willing sacrifice,

Isaac bearing the wood (עץ, ξύλον) for his sacrifice,

Passover, and

the place (םוקמ, τόπος) of Isaac's near-sacrifice—Moriah, where the Temple would later be built.

The New Isaac in the Fourth Gospel

The majority of references to the ‘Aqedah in the Gospel of John are subtle, contingent upon a cumulative case. Therefore, this study will present each of the connections individually, focusing on the most pertinent pericopes in John. We will explore the Father-Son language most extensively since it is the strongest parallel with the Genesis account; this naturally includes the "only-begotten" language that arises in the prologue and John 3:16. Then, Christ's willingness to die, Passover, and the Temple in John's Gospel will be explored. The study concludes with an examination of Christ's Passion (ch. 19) in relation to the near sacrifice of Isaac, noting crucial linguistic and thematic parallels.

The Father-Son Language in the Johannine Literature

One of the best-known aspects of John's Gospel is the Father-Son language that permeates the text. The Synoptic Gospels imply this notion in their "Son of God" language, but it is in John that the filial relationship between Jesus and God is most explicit. This aspect is paramount for our study since one of the major dimensions of Genesis 22 is the notion that Abraham, the father, offered up Isaac, his only son, as a sacrifice to YHWH. In this section I will only explore the most significant passages that illustrate the parallels between the ‘Aqedah and the Fourth Gospel, since there are too many occurrences to explore individually.1

The "Only-Begotten" Son in the Prologue of John (John 1:14, 18)

Contained within John's prologue is not a direct reference to Isaac, if there is one at all. If anything, there is one potential parallel with Abraham and Isaac and a possible preparatory allusion to 3:16 since the Logos is described as µονογενής. As to the first point, there may be an analogous tradition about the two patriarchs lurking behind 1:1–3,

In the beginning (Ἐν ἀρχῇ) was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. This one was in the beginning (ἐν ἀρχῇ) with God. Through him all things came into being, and apart from him there was nothing.

These verses are commonly associated with the notion of the pre-existent Logos, that the Word was in existence prior to the creation of the kosmos.2 In Pr. Jos. fragment A v. 2, the author writes,

καὶ Ἀβραὰµ καὶ Ἰσαὰκ προεκτίσθησαν πρὸ παντὸς ἔργου

Both Abraham and Isaac were created before every work.

Although the two are not precisely parallel, since Abraham and Isaac were created, the relation ship is undeniable.3 Both texts claim that there were beings prior to the creation of the world, which was not a common tradition for the Patriarchs.4 It cannot be proven that this text was in mind when the prologue was composed—it likely was not—but since there are extant traditions that purport the existence of Wisdom, Torah, or Israel before creation (e.g., Prov 8:22; Sir 24:8), then there is a potential relationship between this material and John's prologue.5 The similarities are intriguing: Isaac is listed with Abraham as pre-existent, like the Logos; both the Logos and Isaac are sons (υἱός) of a father; and both are called µονογενής.6

In 1:14 arises the first appearance of µονογενής in John, but it is not accompanied by υἱός. Rather, it is only implied by the Father language mentioned just afterwards.

Καὶ ὁ λόγος σὰρξ ἐγένετο καὶ ἐσκήνωσεν ἐν ἡµῖν, καὶ ἐθεασάµεθα τὴν δόξαν αὐτοῦ, δόξαν ὡς µονογενοῦς παρὰ πατρός, πλήρης χάριτος καὶ ἀληθείας·

And the Word became flesh and settled amongst us, and we beheld his glory, glory as from the only-begotten7 from the Father, full of grace and truth.

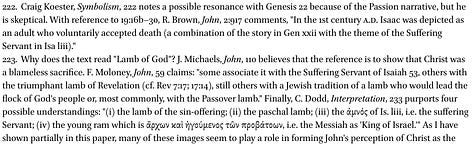

Suffice it to say, there is no direct ‘Aqedah reference in the prologue. There is only a faintly possible, and quite subtle, correspondence with Isaac and Abraham in the first three verses.8 The µονογενής language, though, is a fairly strong indicator that Isaac makes his first appearance here in John.9 There is some contention on how to translate this term, whether it should be "only" or "unique."

Many modern commentators lean towards the latter, but this translation fails to reflect what the author is attempting to convey.10 Since there is such a stark interest in the relationship between the Father and the Son, "unique" does not serve the term justice in context. Yes, Jesus the Christ is "unique" in John, but it is due to his only-begotten status as the only son of God, the Father. Hilary of Poitiers, On the Trinity 6.39, writes:

It seemed to [John] that the name of Son did not set forth with sufficient distinctness his true divinity, unless he gave an external support to the peculiar majesty of Christ by indicating the difference between him and all others. And so he not only calls him the Son but adds the further designation of the Only Begotten. In this way he cuts away the last prop from under this imaginary adoption. For the fact that he is Only Begotten is proof positive of his right to the name Son.

Augustine (Sermon 348a.3) expresses a similar sentiment, which brings sonship in relation to humanity: "He is Son by nature, we by grace; he is the 'only Son,' we are many, because he is born, we are adopted."11 Similar to Isaac, who was the only son of Sarah and the only son of promise, so Christ is of God.

As we explored previously, the terms—µονογενής and יחיד—were used most commonly in association with the meaning "only," especially when used in conjunction with children.12 C. H. Dodd contends that the definition "only-begotten" never arises in the New Testament period, and postulates the term µονογέννητος would be more appropriate if the author desired to reflect this meaning.13 John McHugh's research shows that this cannot be the case since this term never occurs within Greek literature, and µονογενής is sufficient to describe an "only" child.14

Leon Morris comments, "It should not be overlooked that µονογενής is derived from γίνοµαι, not γεννάω (one ν, not two). Etymologically it is not connected with begetting."15 Contra Morris, U. von Wahlde contends, "Although the term is related to the verb gennaō, etymology does not help in a correct understanding."16

From this, we see that there is confusion between these two exegetes whence precisely this term derives.17 If this confusion arises amongst modern commentators, then it certainly could have been the case for the New Testament writers.18 LSJ shows that Brown is likely correct, historically.19

D. Moody also argues against "only-begotten," based upon the etymology of µονογενής.20 Secondly, Moody falls into a linguistic fallacy: he seems to imply that each use of µονογενής in the New Testament must have the same meaning, which is reflected in his comments on Luke 7:12, "The widow's son at Nain is called 'the only (monogenēs) son of his mother,' and surely no one would insist that she begat him!"21 Certainly this is the case, but that does not prove that the term cannot have the connotation "only-begotten." Since it is used in reference to the Father in John, it certainly is the case that it could have the notion of begetting.22

When Moody discusses יחיד, he concedes that in Judg 11:34 the term connotes "only," as well as in Pss 22:20; 25:16; and 35:17. As for the Deuterocanonical books, he claims µονογενής means "only" in Tobit 3:15, and in Wis 7:22, it reflects "unique." Ultimately, Moody defines יחיד first as "dear one" and then "one and only," though, as I have shown, the first and foremost definition historically and contextually is "only," especially in association with children. D. Moody's bias for understanding µονογενής as "unique" has seemingly colored how he perceives the primary meaning of יחיד.

The word µονογενής in the New Testament is used purely as "only" or "only-begotten," its primary meaning within the Septuagint. In English, the idiom, "only-begotten" contains the same semantic meaning as "only child," just from a paternal standpoint. Based upon the linguistic discussion of יחיד and its translation, it is clear that the original Hebrew connoted "only," and "precious" in a few instances where "only" was implied. Likewise, µονογενής is used to mean "unique," but its core meaning is associated with an "only" status. I am willing to discard "only-begotten," but it can be retained despite the re-assessment of Moody, et al. when used in reference to God, the Father, and Jesus, the Son. Take for example Aeschylus' use of µονογενής in Agamemnon lines 895–900, noting specifically Smyth's translation of the term (emphasis my own)

Here we see an example of µονογενής used specifically as I have proposed above. I would therefore argue that on its own, the translation "unique," is misleading.23 As Isaac was the only son of promise, so is Christ the only true son of God, who reveals the Father.

Thus, the connotation of µονογενής prepares the reader to view the Logos as the only son of the Father.24 If one drops the "begotten," the fact still remains that the implication of the verse is that Jesus alone is the Son of God, and this Father-Son theme is paramount for the Gospel.25 He is unique purely because of his status as the "only" son of the Father.26

As such, it is intriguing that the "only-begotten son"27 of v. 18 is also described as ὁ ὢν εἰς τὸν κόλπον τοῦ πατρὸς. This becomes paramount considering how κόλπος is used in reference to Abraham.

Contained within each of these, there is a mention of Abraham's bosom as a place of repose for the dead, which is not directly parallel to 1:18. At the very least, this phrase shows the intimacy between the Father and the Son.28 This reference is not explicit, but it is intriguing that the Word is described as being in the bosom of the Father, which potentially intimates Christ's death and return to the Father. The use of κόλπος in the New Testament is sparse, and two of its occurrences pertain to Abraham and death.

John McHugh comments on the use of εἰς here, "The most satisfactory interpretation, however, is to take ὁ ὢν εἰς τὸν κόλπον τοῦ πατρὸς as referring to the return of Jesus Christ into the bosom of the Father."29 He argues that this interpretation is based upon a classical understanding of εἰς, which does not have the same connotation as ἐν.30

Just prior to this assertion (v. 14), the text speaks of Christ's glory, which in this Gospel is the crucifixion.31 The verse implies that after revealing his glory, he is to return to the Father; it is the conclusion of the subsection, beginning with v. 14, which speaks of the Son coming into the world:

Contained here in these five verses is a summary of Christ's mission. This is the concluding block that segues into the witness of John the Baptist. Verse 18 situates the reader into realizing who the Logos is: he is the incarnate, only-begotten Son of God who will reveal the Father, who will ultimately return to him after his death on the cross.

Κόλπος is also present at the Last Supper, as the physical description of where the Beloved Disciple rested his head (13:23).32 Here, at the beginning of the Gospel, we may have a potential bookend since it is before creation that the Son rests his head in the Father's κόλπος, and then the disciple has his head in the Son's just prior to the revelation of his glory (δόξα), which Christ came to reveal. Contained within 1:14–18 is the foreshadowing of Christ's death.33

The use of κόλπος alone certainly is a stretch for drawing the connection to Jesus' Pascha, but the µονογενής language may add further assistance. If µονογενής was used to invoke an Isaac typology from the outset of the Gospel, then it is plausible. This is especially true considering Jesus' monologue in 3:16 concerning the love of the Father, who gave his only-begotten son.

This will be discussed later at length, but if there is a reference to Isaac in chapter three, then it is quite plausible that the reference begins in the prologue. This is also important for John's theology, if he is working with a typology of a father's sacrificing a son. This seems to be the case considering the thematic elements that are specific to Isaac and the ‘Aqedah that are still to be explored in John.

The glory that is revealed in Christ is his death, which is referenced in these verses alongside µονογενής.34 This is a subtle portent of the climax of the Gospel: Christ's death upon the cross (ξύλον). Therefore, it is probable that the death of Christ is already foreshadowed as an Isaac typology at the outset of the Fourth Gospel.

God's Love Revealed Through His "Only-Begotten" Son (1 John 4:9–10)

Before going into a full discussion of these verses, this study presumes an interconnected relationship between the Gospel and the Johannine Epistles. How precisely these documents are related must be left for another study, but it is important to note that I hold that 1 John is dependent on the Gospel.35

For this reason, 1 John will be treated in this analysis; the letter will be used for understanding certain aspects of John's Gospel. Since the two have a genetic relationship in thought and theology, the corpus of material can be used to understand the beliefs of the author of John and the reception of the Gospel.

Since the Gospel and Epistles are deeply connected, the occurrence of µονογενής in 4:9 is paramount, especially since the language is so similar to John 3:16. C. H. Dodd contends, "Verse 9 is a restatement of the great Johannine declaration of the love of God (John iii. 16) in terms differing only slightly from the form given in the Fourth Gospel."36 Although he does not claim any ‘Aqedah allusions in the text, there are clear linguistic relations between the two Johannine texts,

1 John 4:9—ἐν τούτῳ ἐφανερώθη ἡ ἀγάπη τοῦ θεοῦ ἐν ἡµῖν, ὅτι τὸν υἱὸν αὐτοῦ τὸν µονογενῆ ἀπέσταλκεν ὁ θεὸς εἰς τὸν κόσµον ἵνα ζήσωµεν διʼ αὐτοῦ.

John 3:16—Οὕτως γὰρ ἠγάπησεν ὁ θεὸς τὸν κόσµον ὥστε τὸν υἱὸν τὸν µονογενῆ ἔδωκεν, ἵνα πᾶς ὁ πιστεύων εἰς αὐτὸν µὴ ἀπόληται ἀλλὰ ἔχῃ ζωὴν αἰώνιον.

Despite the fact that the verses are not identical, there is a clear relationship in thought.37 Both seek to express the loving nature of God—the Father sent his only-begotten Son into the kosmos so that life may come through his incarnation (and death).38

George Parsenios claims, "Verses 9–10 demonstrate the definitive act of God's love in sending Jesus Christ, beginning with the incarnation… But the matter is not left at the incarnation. The crucifixion, understood as Christ's sacrifice for sins, is brought into view in verse 10…"39 As such, if this line of thought is true, then my previous discussion on John 1:14–18 holds more weight because therein lies this same thought. The glory of Christ is made real in his incarnation and fulfilled upon the cross "to be the atoning sacrifice for our sins" (1 John 4:10). If the author of John had Isaac in mind when implementing the adjective µονογενής, then it is possibly the case in the Johannine epistle.

Again, we find the trademark Father-Son language of the Johannine corpus. This further adds to the possible Abraham-Isaac typology that we have been exploring. The use of µονογενής in this context adds credence to the claim that John is working with this Isaac typology.40 Raymond Brown contends,

And so the Isaac language was shifted to Jesus, with John using mongenēs and Mark using agapētos (1:11; 9:7 [12:6]), to describe him as God's unique and beloved Son… Seemingly the Johannine writers made a distinction: all the Johannine Christians deserve the designation agapētos, "beloved" (Note on 2:7a), as God's children (teknon), but only Jesus is monogenēs as God's Son (huios). There is, of course, a hint of God's love for His Son in monogenēs, a theme made explicit in John 17:26.41

I agree with Brown's distinction between ἀγαπητος and µονογενής in 1 John, but as I have shown, "unique" or "beloved" for µονογενής is secondary to "only."42 Be that as it may, it is significant that the epistle references Jesus as the Father's only Son. The only named figure (a patriarch) within Jewish literature that is so described is Isaac,43 and it is he alone that is nearly sacrificed.44

These two components are significant considering what is contained within Gen 22:9 and 1 John 4:10:

Gen 22:9b—…καὶ συµποδίσας Ισαακ τὸν υἱὸν αὐτοῦ ἐπέθηκεν αὐτὸν ἐπὶ τὸ θυσιαστήριον ἐπάνω τῶν ξύλων.

1 John 4:10b—…αὐτὸς ἠγάπησεν ἡµᾶς καὶ ἀπέστειλεν τὸν υἱὸν αὐτοῦ ἱλασµὸν περὶ τῶν ἁµαρτιῶν ἡµῶν.

There are no verbal parallels between these two texts, but there is a relationship between θυσιαστήριον and ἱλασµός: both have cultic/salvific connotations.45 One is the instrument upon which the burnt-offering is made, the other is the sacrifice. Raymond Brown states,

the author thought of Jesus as an expiatory sacrifice removing sin, in his role of a heavenly Paraclete standing in the Father's presence making intercession. Here the author is thinking of Jesus' death and not simply of the incarnation when he mentions the sending of the Son as an atonement.46

Secondly, it is significant that God loved (ἠγάπησεν) us so that he sent his son, and God also requested that Abraham offer his only son, whom he loved (ἠγάπησας, cf. v. 2). Again, there is not a direct parallel: God is not described as loving his son, whereas Abraham is. Despite this disanalogy, both passages contain the language of love for another. The parallels with Genesis 22 keep compounding: Father son language, love, µονογενής, and sacrifice.

Finally, ‘Aqedah associations may also arise in 1 John 4:12, 14. These verses have clear parallels with what we have explored in John 1:18,47

1 John 4:12—θεὸν οὐδεὶς πώποτε τεθέαται· ἐὰν ἀγαπῶµεν ἀλλήλους, ὁ θεὸς ἐν ἡµῖν µένει καὶ ἡ ἀγάπη αὐτοῦ ἐν ἡµῖν τετελειωµένη ἐστιν.

John 1:18—θεὸν οὐδεὶς ἑώρακεν πώποτε· µονογενὴς θεὸς ὁ ὢν εἰς τὸν κόλπον τοῦ πατρὸς ἐκεῖνος ἐξηγήσατο.

It cannot be mere coincidence that these verses contain such similarities in proximity: no one having ever seeing God, µονογενής, Father-Son typology, and the revelation of the Father through the Son.

1 John is most assuredly dependent on the prologue of John to develop this theme of love and salvation, which relies on a father sacrificing a son; this paradigm has its most obvious parallel in Judaism with the ‘Aqedah.

If it can be proven that one text has an Abraham-Isaac typology, then it most likely is the case for the other. Verse 14 further adds to this relationship, "and we have beheld (τεθεάµεθα) and we testify (µαρτυροῦµεν) that the Father has sent (ἀπέσταλκεν) his son as the savior of the kosmos."48 The entire notion of salvation through Christ's sacrifice is realized within these verses, and they contain echoes of the ‘Aqedah.

God's "Only-Begotten" Son in John 3:16: A Linguistic Examination

Now we arrive at the climax of this analysis: an exploration of the linguistic components that are shared between John 3:16 and Genesis 22.49 As I have previously shown elsewhere in the Johannine corpus (John 1:14, 18; 1 John 4:9–10), there is a semi-lexical connection with Genesis 22 via the author's use of µονογενής.50 If that be the case in these passages, the likelihood of its existence in John 3:16 is quite plausible.51 J. Ramsey Michaels writes:

[In John 3:16] The analogy that comes to mind is Abraham, and his willingness to offer up his "one and only" son Isaac as a sacrifice in obedience to God (Gen 22:1–14). This analogy, unlike that with Moses and the bronze snake, is never made explicit, but hints elsewhere in the gospel suggest that what God asked of Abraham was something God himself would do in the course of time.52

As I have illustrated, this is the case. The Abraham-Isaac relationship is parallel to the Father-Son typology employed in the Gospel of John, which permeates the Gospel.

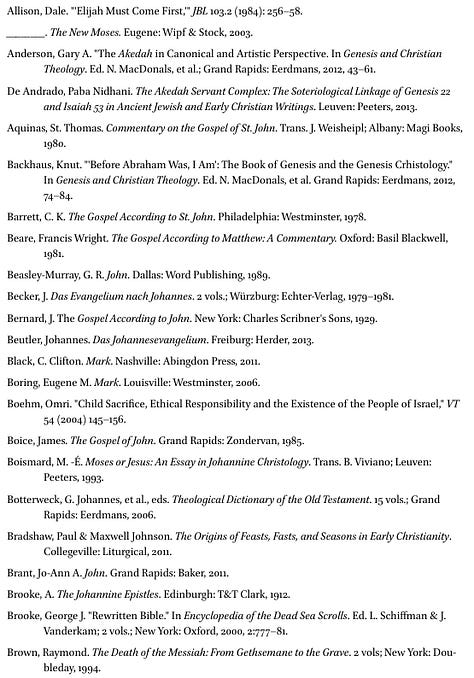

Let us now examine the textual tradition of John 3:16 in relation to Gen 22:2a and its recensions in order to solidify any potential parallels:

Our research has shown that there must have been a divide between µονογενής and ἀγαπητός by the first century AD, but there still remained some semantic overlap. This fluidity is best seen in the translation of Gen 22:2a.53 If the reader examines the chart above, יחיד has been translated in four different ways. LSJ defines the terms as follows:54

Notes 147 & 148:

From this lexicographical evidence, one can state fairly confidently, that in classical Greek, the three terms do not primarily signify a notion of "beloved."55 Even ἀγαπητός, whose root is ἀγαπάω, does not principally have this connotation; instead, it is used most closely with the sense of an only child. Ἀγαπάω has the primary definition of "greet with affection" and secondarily "to desire." Ἀγαπητός also has the notion of "desire" in a secondary definition, and it can mean "beloved." LSJ, though, lists no examples of children, as with its first definition.

Many commentators wish to associate µονογενής with "unique" in John56 because "only-be gotten" appears in Jerome's Vulgate to battle Arianism, which can be witnessed in the two Latin translations provided above. OL provides "only" instead of "only-begotten." Primarily, µονογενής seems to connote neither "unique" in classical literature57 nor in the Fourth Gospel.58

Rather, µοναχός may have been a better choice, though it does not appear within the New Testament.59 Alternatively, this term can also be used in association with an only child. I do not wish to completely discard this possible connotation in John, but if it does appear, it is only secondary to the primary point: Jesus is the Father's only(-begotten) son.60

The context lends itself towards favoring a definition that is more closely related to sonship, which would require "only" or "only-begotten" over "unique." Since each term listed above can be used in reference to an "only" child, that is most likely what the Greek translation meant for Genesis, and there was disagreement amongst the translators just how to reflect that meaning from יחיד.

Within this section, we have already explored the use of µονογενής aside from John 3:16. Since ἀγαπητός appears 61 times in the New Testament, there will not be a full explication of each instance. Rather, I will chart the general uses of the term and provide an analysis of only those passages most pertinent for this study.

The reader can see that there is a primary use of the term: "beloved," and this is reflected in how it is usually translated into English (NRSV).

In each category except the first, the only definition that makes any logical sense is "beloved" or "cherished," since "only" would make little sense in context. This is especially so in the epistles, where the author appeals to the audience as ἀγαπητοί, cast in the plural. The final three uses also presume multiple children, slaves, or siblings; the metaphor is used for fellow-Christians, creating a familial structure in the Church.

The first grouping, though, is more ambiguous. The references to Jesus are in two places: the baptism and transfiguration.61 These instances are likely alluding to Old Testament passages, so the author's use of ἀγαπητός was done to echo these verses.62

The term's use in parables (Mark 12:6; Luke 20:13), however, have the sense that the son is beloved on account of his being the only one. Since these pericopes are meant to serve as a metaphor for Christ, it certainly could be the case that "only" is in mind since the Gospels in no way imply that God has children other than Jesus. The usage in Matt 12:18 is likely "beloved" or a semantic equivalent such as “choice servant.” Lastly, 2 Pet 1:17 quotes the voice from the synoptic baptism account, so its meaning is parallel to those.

BDAG lists two primary definitions for ἀγαπητός:

This lexicon reflects the possible semantic overlap of the two terms, since the primary meaning listed is "only" or "only beloved." This is an apt definition since the term holds both connotations when used in particular circumstances: if the child is the only one of the parents, it would naturally follow that he or she would be dearly beloved.63

In John, this distinction is likely present. C. K. Barrett states with regards to 3:16, "The mission of the Son was the consequence of the Father's love; hence also the revelation of it. ἀγαπᾶν, ἀγάπη, are among the most important words in John."64 The theme of "love" is paramount in the Fourth Gospel, so it may be surprising that John did not choose to call Jesus ἀγαπητός here and in the prologue, which would be another convenient tie-in with God's love. However, as seen in the New Testament, this term does not possess the notion that John wished to impart to his audience. He wants to make it explicit that Jesus is the only son of the Father.

John may have also used µονογενής on account of the lexical similarities of how Isaac is described in extra-canonical texts, which can be seen in Josephus Ant. 1.222:65

The parallel is not direct: John states that God loves the world, and on account of this love he sent his only son. Nevertheless, the texts that we have explored concerning Isaac have shown that µονογενής is a common epithet for the patriarch. Thus, we again see the clustered characteristics of father-son language, µονογενής, love, and sacrifice.66

The suggestion of the ‘Aqedah in John 3:16, based upon the author's use of µονογενής, is frequently mentioned.67 In addition to this, I have shown throughout how both of these terms have been used in relation to Isaac, but some scholars still object to the allusion. Craig Keener states, "Some may overemphasize Aqedah allusions here (e.g. Grigsby, 'Cross'; Swetnam, Isaac, 84–85)," but concedes that "the expression 'unique Son' adds pathos to the sacrifice, drawing on an image like Abraham's sacrifice of Isaac."68 Keener redirects the reader to his discussion of 1:14 concerning the Logos as µονογενής (412–419) wherein he illustrates the use of µονογενής in other extant literature. In short, Keener supports my claim more than he undermines it. First, he states that µονογενής is an acceptable translation for יחיד:

the term came to connote "beloved" as much as "only," and it is this nuance which probably comes to the forefront in Johannine usage… Because µονογενής often translates יחיד, and יחיד could also be rendered ἀγαπητός (as with Isaac, who was called יחיד though he was not technically Abraham's "only" son, Gen 22:2), it was natural that µονογενής should eventually adopt nuances of ἀγαπητός in biblically saturated Jewish Greek.69

If µονογενής and ἀγαπητός are semantically interchangeable due to "biblically saturated Jewish Greek," it is at least plausible that John wished to parallel the Father's giving of his only son to the Binding of Isaac. This is compounded by the thematic parallels that we have witnessed throughout the Gospel.70

The final linguistic component that we will explore is ἔδωκεν. Jon Levenson writes:71

"Gave" (edōken) reflects the usual language of child sacrifice in the Hebrew Bible, beginning where we began our own discussion, with Exod 22:28b—"You shall give (titten) Me the first-born among your sons"—and continuing throughout the tradition of the Hebrew Bible, including Ezekiel, who describes the immolation of the first-born as the presentation of a "gift" (mattānâ, Ezek 20:31).72

Here there is a parallel with another text that is hypothesized to have echoes of the ‘Aqedah. Rom 8:32 reads, ὅς γε τοῦ ἰδίου υἱοῦ οὐκ ἐφείσατο, ἀλλὰ ὑπὲρ ἡµῶν πάντων παρέδωκεν αὐτόν… This could be evidence that a similar tradition exists in both Paul and John. If one examines Gen 22:12b, νῦν γὰρ ἔγνων ὅτι φοβῇ τὸν θεὸν σὺ καὶ οὐκ ἐφείσω τοῦ υἱοῦ σου τοῦ ἀγαπητοῦ δι᾽ ἐµέ, one notices that both texts share a linguistic and a thematic element.

The only verbal parallel between Romans and Genesis is their use of φείδοµαι. Thematically, both speak of an "only" son, ἰδίου/ἀγαπητοῦ.73 Commentators speculate on the connection between the two, but the language of not sparing an only son has its only parallel in Jewish literature with the ‘Aqedah.74 The verbal parallel of "giving"75 in Rom 8:32 and John 3:16 likely connects them.76

John McHugh comments on the probable relationship, "While Paul stays closer to the LXX, with οὐκ ἐφείσατο, John stays closer to the Hebrew, but in place of the Hebrew, did not withhold (חשך, ḥśk), he writes, more positively, gave."77 Therefore, since both authors included the notion of the Father's sacrificing the Son, they appear to reflect Leven son's comment on ἔδωκεν as having a cultic/sacrificial connotation. An allusion to the ‘Aqedah is highly probable.78

The Father-Son language compounded with µονογενής is the strongest argument that can be made for the parallel. Abraham and Isaac alone have a father-son relationship wherein the father sacrifices a son, who is called "only." Therefore, the use of that adjective, plus the thematic parallels explicated below, lend considerable weight to the proposition that Isaac has served as a backdrop for Christ in this verse and throughout the Fourth Gospel.

Christ as a Willing Self-Sacrifice

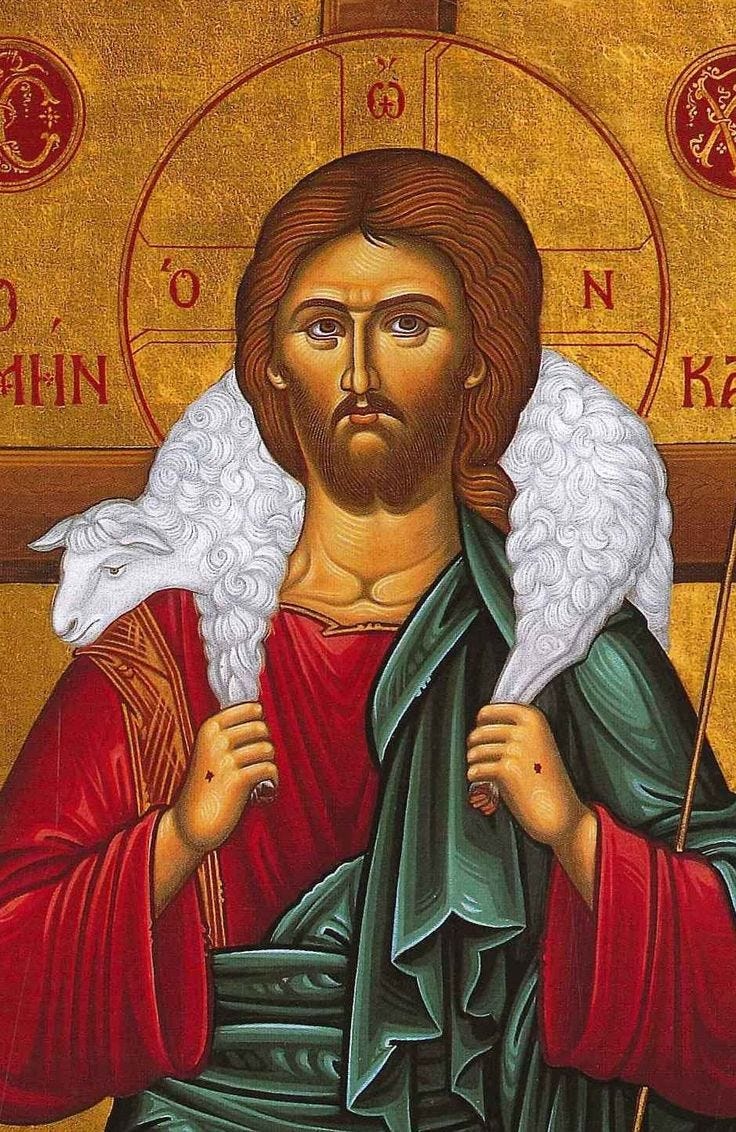

Christ's willing sacrifice is particularly explicit in the Fourth Gospel, similar to how zealous Isaac is depicted within extra-canonical literature. Jesus speaks of the interconnected nature of his authority and death throughout the Gospel.79 John 10:1–21 offers one of the strongest affirmations of self-sacrifice.80 Jesus discusses how he is the Good Shepherd who pastors his sheep, who know his voice. In vv. 11, 15, 17–18 he states:

I am the good shepherd. The good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep… And I lay down my life for the sheep… For this reason the Father loves me, because I lay down my life in order to take (λάβω)81 it up again. No one takes it from me, but I lay it down of my own accord. I have power to lay it down, and I have power to take it up again. I have received this command from my Father.

Here, Jesus reveals the full extent of his authority. No one can put him to death; it is he and he alone who decides when he will die.82 The pericope is a portent of the life that Jesus will lay down for many so that they might be saved—it points forward to the crucifixion.83 Droge and Tabor argue, "The voluntary nature of Jesus' death is emphasized above all in the Fourth Gospel by that author's remarkable interpretation of the arrest, trial, and execution of Jesus. Throughout the Johannine account of the passion, Jesus' authority is repeatedly stressed."84

Here, though, there may be a bit of a disruption in the logic that Jesus is the Lamb of God. He is now identified with the shepherd. However, Keener states, "The shepherd's willingness to lay down his life for the sheep (10:11) may connect him with the lamb (1:29)."85 In any event, it is not out of the ordinary for a New Testament author to have multiple images working at once even if a slight paradox arises.86

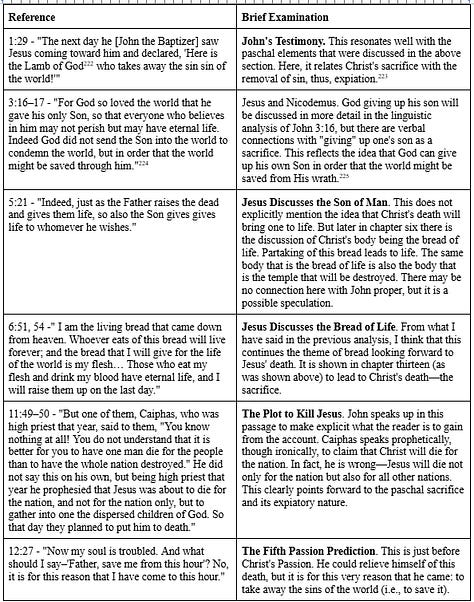

The Importance of Passover in John

The paschal elements that exist in the Gospel are of crucial importance for seeing the underlying Isaac tradition and for understanding how John perceives Christ's death.87 The Passover is mentioned explicitly or implicitly ten times—eight of which occur solely in the Passion narrative.88 John, like the author of Jubilees, is concerned with the dating, which is evidenced by the references to Jewish festivals frequently during Jesus' ministry.89 The mention of Passover90 periodically in the text pushes the narrative along as a reminder of Jesus' Passion, although these references appear less frequently in the middle and end of the Gospel (with the farewell discourse breaking up the flow). The first two occur in chapters two and six.

In 2:13–25, Jesus cleanses the Temple. The pericope begins by stating, "The Passover of the Jews was near, and Jesus went up to Jerusalem." Jesus utters his first passion prediction in the context of the Temple.91 The Temple is an intriguing aspect of this pericope because the author explains in v. 21 that the Temple's destruction is a metaphor for Christ's body.92 Jesus alone has the authority to surrender his body (10:17–18). This also correlates with the Good Shepherd motif in John 10:11. Jesus will choose to die and raise himself up because he has the authority to do so.93

The accounts of the feeding of the five thousand, Jesus walking on water, and the speech by Jesus as the bread from heaven (6:1–59) are temporally framed around "the Passover, the festival of the Jews" in 6:4. The Passover setting of these scenes is significant because it reminds the reader of the climax of the Gospel: the Passion.94

The feeding of the five thousand has more direct eucharistic overtones in the Synoptics (possibly),95 but here it is part of an intercalation. The account of Jesus walking on water is lodged between two accounts that discuss bread (ἄρτος).96 The overall importance concerns the discussion of Jesus as the Bread of Life. In 6:33 Jesus claims, "For the bread (ἄρτος) of God is that which97 comes down from heaven and gives life to the world." This forms a connection with the feeding of the five thousand.98

The two accounts are similar to a Marcan sandwich with the walking-on-water account in between. More important: the bread points forward to John 13:18, which initiates the Passion. John writes,

I know those whom I have chosen. But in order that the Scripture might be fulfilled, “The one who eats my bread (ἄρτος) has raised his heel against me.”

Later (v. 26) in connection with the one of whom he spoke, Jesus says,

“It is the one to whom I give99 this piece of bread (ψωµίον) when I have dipped it in the dish.” So when he had dipped the piece of bread (ψωµίον), he gave it to Judas son of Simon Iscariot."100

Chapter 6 contains almost all the occurrences of ἄρτος in the Gospel, and so the word's appearance here is significant. It connects the feeding narrative with the bread-of-life language with the Passion.101 These are all within the confines of the Passover, which itself contains the breaking of bread (cf. Pesahim 10.1.3ff.).

All the paschal language throughout the Fourth Gospel serves as a constant reminder that Christ will be offered as the sacrifice, for he is the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world.102 As the narrative draws closer and closer to Christ's final hour, it becomes more apparent that he will die in order to save not only the nation of Israel, but all the nations.103

As the figure above shows, the author is concerned with the audience realizing the temporal frame in which the entire Passion narrative takes place. Chapter 11 leaves the time quite ambiguous stating, as he did earlier, that the Passover was "near." In the next pericope, though, John claims the Passover is only six days away. This closely resembles Jubilees wherein the author conducts a similar ploy concerning when the ‘Aqedah occurred. In John 12 the author notes that it is the next day and the Jews came for the festival, the implication being that it is now five days prior to Passover. Henceforth, the mention of the Passover is more nebulous as to how many days remain until 19:14, which mentions the Day of Preparation, on which the lambs were sacrificed.104 It is on this day that Jesus is handed over to be crucified and the timeline is complete.105 All of these references to the Passover point to Jesus' identity as a paschal sacrifice.

The final paschal allusions occur at the crucifixion (19:29). Striking among these is the mention of the hyssop that is used to bring the sponge up to Jesus' lips. Bultmann unnecessarily rejects the paschal element asserting:

It is also very doubtful that a further allusion to the significance of the event is contained in the fact that the sponge filled with vinegar is stuck on a hyssop reed (so Mk. and Mt in stead of the simple κάλαµος). Purifying power was ascribed to hyssop (Lev. 14.6ff.; Num. 19.6; Ps. 50.9; Heb. 9.19; Barn 8.1, 6), and the blood of the Passover lamb had to be sprinkled on the lintel and posts of the door by means of a bunch of hyssop (Ex. 12.22). But it is scarcely believable that Jesus should be designated as the Passover lamb through the state ment that a sponge with vinegar was stuck on a hyssop stem.106

This rejection is unwarranted, especially since elsewhere Bultmann asserts that John understands Jesus to be a paschal sacrifice.107 If one believes that John has knowledge of Mark, then one could argue more strongly that the change is intentional and was done to fit John's theological frame work. Bultmann's appeal to Joach who reads ὕσσῳ (lance) in place of ὑσσώπῳ from miniscule 476 is more speculative than what I propose.108 When Bultmann wrote, "Hyssop indeed is not particularly suitable for the purpose," he is most certainly right, but that does not mean that the image should be discarded because the instrument does not make logical sense in the practical situation.109

Excursus: The Synoptic Chronology of the Passion and John's

There has been much contention over the dating of Christ's actual crucifixion due to the conflicting timelines of the synoptics and John. Many commentators have attempted to harmonize the accounts by asserting that the two are reckoning time based on differing calendars,110 but the gospels betray such a hypothesis.

Observe that the synoptic tradition contains more or less the same rendering in the initial verse: it was the first day of the Feast of Unleavened Bread when the paschal (lamb) was sacrificed; Matthew lacks the second phrase, though. Notice also that Mark and Luke render the paschal sacrifice almost identically to Exodus and 1 Corinthians.111 From these texts, we can discern that the chronologies are conflicting; in the synoptics, the "Last Supper" occurred on Pascha whereas John 19:1 clearly states that it was the Day of Preparation for the Pascha (παρασκευὴ τοῦ πάσχα) when Jesus was crucified.112

The history of interpretation for John 19:14 has varied on this point, since many translators have attempted to assess this minor "hiccup." Theodore of Mopseustia, Commentary on John 7.19.14, mentions that some call the gospels into question on this point, but the focus concerns the time at which Christ was crucified rather than on the date; so also does Augustine, Tractates on the Gospel of John 117.1.113 Eusebius of Caesarea, Minor Supplements to Question to Marinus 4, chalks it up as a scribal error. Peter of Alexandria, Fragment 1.7, affirms that "Jesus did not eat of the lamb, but he himself suffered as the true Lamb in the Paschal feast" (14 Nisan).114

Most modern commentators concede that John's crucifixion narrative differs from the synoptics and that the narrative event occurred on the Day of Preparation when the lambs were sacrificed.115 Another discussion concerns whether παρασκευή signifies preparation for the Sabbath116 or Pascha.117 Strikingly, I found no com mentator who extensively argues why John differs from the synoptics. Regardless, both accounts associate Christ's Passion with the Pascha.

The Relationship between Jesus’ Body and the Temple

I showed previously that there is a strand of tradition that relates the Binding of Isaac and Moriah with the Temple. This strand can be seen in the Gospel as well. The logic of my argument is as follows: The ‘Aqedah is a prefiguring of the Temple; the Temple is the location where all other sacrifices occurred (modeled after Isaac's); the Temple, which Jesus frequents, remains associated with this notion; thus, it is significant that every time the Temple is mentioned in association with Jesus, violence is suggested whether it be a Passion prediction, the Jews seeking to stone him, or the officials plotting to arrest him.

There are nine instances in which this occurs.118 In summary, the violence associated with the temple in John seems to reflect the sacrificial aspects that resonate with cultic practices.119 The Lamb of God is treated with hostility whenever he approaches the place where sacrifices happen. In the end, he is glorified in his death because his is the perfect sacrifice that Isaac's was not.

Thus, as Second Temple authors connected the ‘Aqedah as the prefiguring of the cultic practice in the Temple at Jerusalem, so does John.120 Such violence resonates with Jesus' paschal sacrifice. These two points are connected more directly when one considers the phrase proclaimed by John the Baptist, "Behold the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world" (1:29) and God's giving of the Son so that all might be saved (3:16).121 This then entails the notion of expiation in the Gospel since the Temple and sacrifice are mentioned.

The paschal sacrifice was not normally connected with redemptive properties,122 but there are writings in Jewish literature that make such an association with Isaac.123 Within the Gospel of John, there are a plethora of instances in which the author explicitly states the redemptive nature of Christ's sacrifice or strongly implies it:

From these instances the reader should gather that redemption/expiation is a constant theme throughout John, that Jesus came to impart life on the world. As I have shown, this theme relates to Christ's expiatory sacrifice. It is through his death that the sins of the world are removed. The Gospel opens in 1:29 with the theme of the Passover and expiation: the author believes the two concepts are interconnected. This verse is the lens through which the reader must approach John in order to understand why Christ was sent.

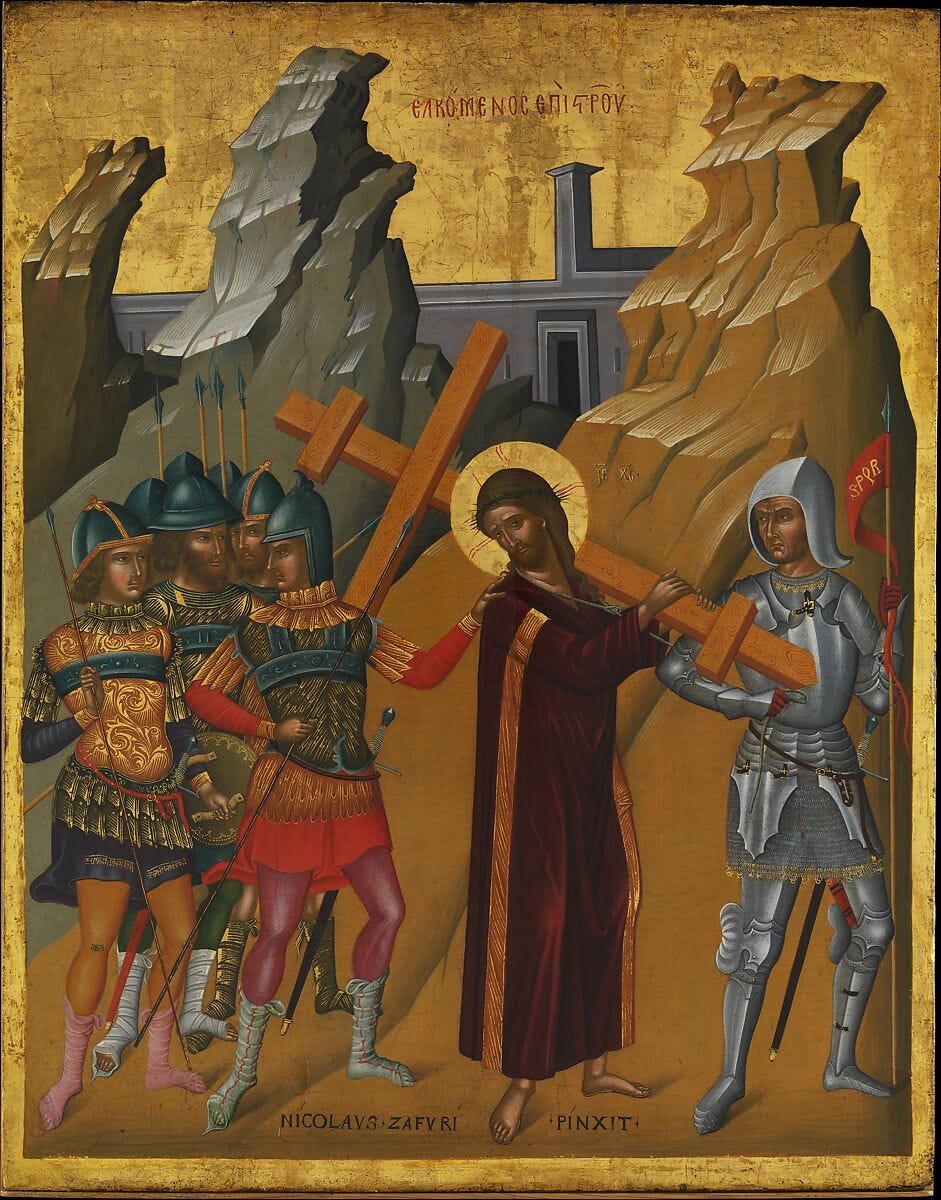

Christ & Isaac's Passions Converge

Our final examination will consist of analyzing the lexical connections between John 19, specifically vv. 16–17, and Genesis 22.124 The significant sections from Genesis 22 are vv. 2 and 9. The LXX renders them as follows,

Gen 22:2 καὶ εἶπεν Λαβὲ τὸν υἱόν σου τὸν ἀγαπητόν, ὃν ἠγάπησας, τὸν Ισαακ, καὶ πορεύθητι εἰς τὴν γῆν τὴν ὑψηλὴν καὶ ἀνένεγκον αὐτὸν ἐκεῖ εἰς ὁλοκάρπωσιν ἐφ᾽ ἓν τῶν ὀρέων, ὧν ἄν σοι εἴπω.

Gen 22:9 ἦλθον ἐπὶ τὸν τόπον, ὃν εἶπεν αὐτῷ ὁ θεός. καὶ ᾠκοδόµησεν ἐκεῖ Αβρααµ θυσιαστήριον καὶ ἐπέθηκεν τὰ ξύλα καὶ συµποδίσας Ισαακ τὸν υἱὸν αὐτοῦ ἐπέθηκεν αὐτὸν ἐπὶ τὸ θυσιαστήριον ἐπάνω τῶν ξύλων.

I have highlighted the words that are of most importance.125 These terms are quite common, but, considering their close ties to the ‘Aqedah, these resonances are quite suggestive. Turning to John, in chapters 18 and 19 the notion of "seizing" is prominent. The word λαµβάνω is used:126

(18:31) εἶπεν οὖν αὐτοῖς ὁ Πιλᾶτος· Λάβετε αὐτὸν ὑµεῖς, καὶ κατὰ τὸν νόµον ὑµῶν κρίνατε αὐτόν.

(19:1) Τότε οὖν ἔλαβεν ὁ Πιλᾶτος τὸν Ἰησοῦν καὶ ἐµαστίγωσεν.

(19:6) ὅτε οὖν εἶδον αὐτὸν οἱ ἀρχιερεῖς καὶ οἱ ὑπηρέται ἐκραύγασαν λέγοντες· Σταύρωσον σταύρωσον. λέγει αὐτοῖς ὁ Πιλᾶτος· Λάβετε αὐτὸν ὑµεῖς καὶ σταυρώσατε, ἐγὼ γὰρ οὐχ εὑρίσκω ἐν αὐτῷ αἰτίαν.

(19:16) τότε οὖν παρέδωκεν127 αὐτὸν αὐτοῖς ἵνα σταυρωθῇ. Παρέλαβον οὖν τὸν Ἰησοῦν·

With respect to Genesis 22, it could be merely coincidental that John used λαµβάνω in these in stances: it is a common word. However, his use of the verb becomes more significant when juxtaposed with other terminology characteristic of the ‘Aqedah tradition. It is crucial to keep in mind what the author wrote in 1:11, which, in this present context, is quite ironic: εἰς τὰ ἴδια ἦλθεν, καὶ οἱ ἴδιοι αὐτὸν οὐ παρέλαβον. The irony is made most explicit when one considers how the narrative has played itself out: Christ came into this world, and he was not "received" by those for whom he came. In another sense, however, they ironically did "accept" him in the sense that they took him and crucified him.

The next verbal parallel is ὑψηλήν. The construction in Genesis is unique because the Sep tuagint translator chose to render אֶל־אֶ֖רֶץ הַמֹּרִיָּ֑ה וְהַעֲלֵ֤הוּ שָׁם֙ as τὴν γῆν τὴν ὑψηλὴν.128 Genesis does not describe the place as "high" but, rather, just calls the location "Moriah": a site that Abraham must "ascend."129 As for John's Gospel, the root ὑψηλ- plays an important role:

(3:14,15) καὶ καθὼς Μωϋσῆς ὕψωσεν τὸν ὄφιν ἐν τῇ ἐρήµῳ, οὕτως ὑψωθῆναι δεῖ τὸν υἱὸν τοῦ ἀνθρώπου, ἵνα πᾶς ὁ πιστεύων ἐν αὐτῷ ἔχῃ ζωὴν αἰώνιον.

(8:28) εἶπεν οὖν ὁ Ἰησοῦς· Ὅταν ὑψώσητε τὸν υἱὸν τοῦ ἀνθρώπου, τότε γνώσεσθε ὅτι ἐγώ εἰµι, καὶ ἀπʼ ἐµαυτοῦ ποιῶ οὐδέν, ἀλλὰ καθὼς ἐδίδαξέν µε ὁ πατὴρ ταῦτα λαλῶ.

(12:32–33) κἀγὼ ἐὰν ὑψωθῶ ἐκ τῆς γῆς, πάντας ἑλκύσω πρὸς ἐµαυτόν. τοῦτο δὲ ἔλεγεν σηµαίνων ποίῳ θανάτῳ ἤµελλεν ἀποθνῄσκειν.

Etymologically, the adjective found in Genesis 22 and the verb in John are related, both meaning "high" or "to lift up." I believe this is particularly intentional. The association of Isaac's sacrifice on a high (ὑψηλή) hill and Christ's being lifted up (ὑψόω) on a cross requires no stretch of the imagination.130 The most significant passage that draws the two together is 12:32–33 which mentions both ὑψηλ- and γῆ in the context of a Passion prediction. Just previously in chapter 12, Jesus asserts, "The hour has come for the Son of Man to be glorified" (v. 23). John is drawing on these words to bring to mind the sacrificial death of Christ prefigured in Isaac.131

Finally, two words, ἦλθον and τόπος, are juxtaposed both in Genesis and in John 19:17. As Abraham approaches the place where he is to sacrifice Isaac, so, too, is Christ. Christ and Isaac were both carry the ξύλον upon which they both were sacrificed.132 The pertinent Johannine verses are as follows:

(19:17) καὶ βαστάζων αὑτῷ τὸν σταυρὸν ἐξῆλθεν εἰς τὸν λεγόµενον Κρανίου Τόπον, ὃ λέγεται Ἑβραϊστὶ Γολγοθα,

(19:20) τοῦτον οὖν τὸν τίτλον πολλοὶ ἀνέγνωσαν τῶν Ἰουδαίων, ὅτι ἐγγὺς ἦν ὁ τόπος τῆς πόλεως ὅπου ἐσταυρώθη ὁ Ἰησοῦς· καὶ ἦν γεγραµµένον Ἑβραϊστί, Ῥωµαϊστί, Ἑλληνιστί.

(19:41) ἦν δὲ ἐν τῷ τόπῳ ὅπου ἐσταυρώθη κῆπος, καὶ ἐν τῷ κήπῳ µνηµεῖον καινόν, ἐν ᾧ οὐδέπω οὐδεὶς ἦν τεθειµένος·

It is intriguing that τόπον appears in connection with ἦλθον as it does in Genesis 22, granted John adds the prefix ἐξ- to the verb. Although this allusion is not concrete, since John is describing the last "hour" of Christ, and the sacrifice is about to be under way, as in Gen 22:9, this is a possible echo. John most likely did not intend this to be explicit, but the entire episode resonates with Passover and ‘Aqedah overtones. This is made most lucid if the reader considers the discussion in John 11 concerning Christ's death so that the Holy Place might be saved.

Since human sacrifice would never be permitted in the Temple, John makes the connection here by using the word τόπος.133 Thus, within the passion narrative, Christ was the perfect offering sacrificed in an appropriately symbolic place.134

When one considers the Gospel as a whole, it is quite plausible that this motif exists here. I made the case previously that there is a connection between the cross and ξύλον in the Early Fathers. Since there is a thematic connection between Isaac ἐπὶ τὸ θυσιαστήριον ἐπάνω τῶν ξύλων and Christ's being raised (ὑψόω) on a σταυρόν (which is made τοῦ ξύλου), my claim that Isaac's near sacrifice served as a backdrop to Christ's passion is plausible. Because the "place" is mentioned three times in reference to the crucifixion, it solidifies the allusion even more.

Conclusion

The lamb of God met his demise at the climax of the Gospel. Christ served as the perfect paschal sacrifice, sentenced at the sixth hour on the Day of Preparation to be slaughtered. The High Priest gave his consent for this act to take place in order to save the Temple and the nation. In light of the ‘Aqedah, Jesus became the confluence of many streams of Jewish tradition. This study has shown that there are significant points of contact between John and the development of thought surrounding Abraham's near sacrifice of Isaac. The ‘Aqedah is not the only narrative that influenced John's theology of atonement and depiction of Christ's sacrifice, but it certainly was a significant trope in the Gospel that deserves more attention than it has lately received.

Bibliography in Note below.135

If you wish to see the potential influence of John on early Christian paschal practices, see my published article. It is directly dependent on this research.

If you enjoyed reading my senior thesis on John’s use of the ‘Aqedah, would you kindly subscribe?

There are many other instances in the Gospel that appeal to this Father-Son language: e.g., 1:34, 49; 3:16–18, 35-36; 5:18–23, 25-26, 36, 43; 6:27, 32, 37, 40; 8:16–19, 28, 42; 10:29, 36; 11:4, 27; 12:34; 14:10, 13; 17:1; 19:7; 20:17, 31.

From the Early Church, consult John Chrysostom, Homilies on the Gospel of John 4.1; Augustine, Sermon 196.1; Cyril of Alexandria, Commentary on the Gospel of John 1.1; Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 1.2.2–3; Theodore of Mopsuestia, Commentary on the Gospel of John, fragment 2.1, 1–2.

Philo discusses the logos as πρωτόγονος—"first-born"— in De Agric. 51; De cofus. Ling. 63.146; De Somn. 1.315. See M. Boismard, Moses, 109.

J. Smith, "Prayer," 2:713 writes, "The term 'created before' (lit. 'pre- created') occurs only here and in late Christian texts. The notion that wisdom, Torah, or the nation Israel were pre-existent is quite widespread in Jewish materials. Less common is the claim that the patriarchs or Moses were pre-existent." Smith also notes in the margins the possible parallel to John 8:58, "Before Abraham was, I Am (ἐγὼ εἰµί)."

According to K. Backhaus, "Before," 83, Paul, John, and the author of Hebrews use Genesis as a backdrop for Jesus' pre-existence. He states, "In sum, the book of Genesis and Abraham serve here to open the perspective for the eternal origins of Christ." There is no mention of this prayer, though.

J. Bernard, John, 24 comments, "And in every place where Jn. has µονογενής (except perhaps in this verse), viz. 118 316. 18, 1 Jn. 49, we might substitute, as Kattenbusch has pointed out, ἀγαπητός for it, without affecting the sense materially." As we have explored earlier, this may not be the case. Regardless, there was still some lexical fluidity between these two words in the first century, but only in specific contexts.

John McHugh, John 1–4, 58 remarks, "In the older English versions, µονογενής was translated as 'only begotten,' but twentieth-century versions nearly all prefer 'only Son.' The danger with this new rendering is that it makes no distinction between the use of µονογενής without the accompanying υἱός (as here, and perhaps in v. 18), and its recurrence with υἱός in 3.16, 18." He concludes that the term should be rendered, "unique"; cf. his third excursus on the prologue, p. 97–103. If there is any sense of "unique" in the term, it is derived from the primary meaning of the word, "only." The sonship in John is so paramount, it must indicate that Christ is the Father's "only" son, which makes him unique. See C. Barrett, John, 166; Benedikt Schwank,Johannes, 37 translates µονογενής as Einzigerzeugten.

In all likelihood, John has no knowledge of this text. If anything at all, he is aware of a related tradition. This is the more likely case since his pre-existent Logos typology is akin to pre-existent Wisdom. That connection is much stronger with Wisdom than Abraham and Isaac, but the idea that Jesus, a human,—we are not delving into the Christological understanding of Jesus in later centuries—is pre-existent has this interesting similarity to the Prayer of Joseph. For a brief discussion on Logos/Sophia, see J. Brant, John, 41. For a longer analysis, see C. Barrett, John, 151–56.

Johannes Beutler, Johannesevangelium, 94, comments, "Er ist »einzige« Sohn, was an Isaak nach Gen 22,2 denken lässt," though he provides no lengthy discussion, as does E. Hoskyns, Fourth Gospel, 150.

Such as J. Brant, John, 35; U. von Wahlde, Gospel, 2:11–12; J. McHugh, John, 97–103; L. Morris, John, 93.

Both translations are from T. Oden, Ancient, 4a:55.

R. Brown, John, 13 and others attempt to argue based upon the Latin translations how to understand its meaning. Brown comments, "The OL correctly translated it as unicus, 'only,' and so did Jerome where it was not applied to Jesus. But to answer the Arian claim that Jesus was not begotten but made, Jerome translated it as unigenitus, 'only begotten,' in passages like this one (also i 18, iii 16, 18)." Although this is an interesting point, and worth mentioning, the historical and contextual observations I provide are more compelling than the Latin. The Arian controversy likely plays a role in this discussion, but that does not mean that John does not already have the sense in his text. If he conceives of Jesus as the Son of the Father, the image/metaphor lends itself to begetting progeny.

C. Dodd, Interpretation, 305 n.1.

J. McHugh, John, 100.

L. Morris, John, 93 n. 101.

U. von Wahlde, John, 2:11.

R. Brown, John, 1:13 comments, "Literally the Greek means 'of a single [monos] kind [genos].' Although genos is distantly related to gennan, 'to beget,' there is little Greek justification for the translation of monogenēs as 'only begotten.'"

These writers are also unaware of historical developments of the Greek language. As such, their etymologies are typically erroneous. For instance, Philo believes there is an association between πάσχα and πάσχω, when the two are not related; see On the Preliminary Studies 106. These writers commonly use false-etymologies for their arguments, so it could be the case that they understood µονογενής as "only-begotten" based upon a misunderstanding of the word's derivation.

LSJ II. -γενής, ές, Ep. and Ion. µουνο-, (γένος) the only member of a kin or kind… -γονος, Ep. µουνό-, η, ον, only-born, of Persephone, Opp.H.3.489 codd. F. Büchsel, "µονογενής," TDNT 4:738 comments, "The µονο- does not denote the source but the nature of derivation. Hence µονογενής means "of sole descent," i.e., without brothers or sisters." He does note that the term's derivation likely comes from γένος, and not birth.

D. Moody, "God's," 213–19.

D. Moody, "God's," 216.

C. Barrett, John, 166 agrees, "Moreover, though µονογενής means in itself 'only of its kind,' when used in relation to father it can hardly mean anything other than only(-begotten) son…" See also Büchsel's comments above.

D. Moody, "God's," 219 closes his argument with 1 Clem 25:2, which discusses the Phoenix, which is "the only one of its kind (monogenēs)." After quoting the verse, he states "Now the Phoenix was neither born nor begotten, but it could be monogenēs, the only one of its kind." All Moody has done is show the semantic range of the term; he has failed to prove that µονογενής cannot mean "only-begotten." If it can signify an "only" child, then one could translate the term as "only-begotten" of a father, if that is the case, or if it is what the author wishes to imply. In the case of John, Jesus is the only genetic son of the Father, the believers are adopted children, so "only-begotten" is a most apt way of describing the Father and the Son's relationship.

St. Thomas Aquinas, Commentary, 92 comments, "So, Christ is called the Only Begotten of God by nature; but he is called the First-born insofar as from his natural sonship, by means of a certain likeness and participation, a sonship is granted to many." When quoting Matt 17:5, his translation reads "beloved Son" (91), which shows that he is possibly making lexical distinctions.

Consult C. L'Eplattenier, Jean, 30.

E. Haenchen, John, 1:120 remarks, "The term 'only begotten' (µονογενής), which appears first in John 1:14, means the only (and therefore especially beloved) son, who enjoys a privileged position."

The text-critical difficulties will not be discussed here since the reference is to the Son, however those problems be resolved. Consult J. Brant, John, 36–37.

Most argue for this interpretation. See J. Brant, John, 36–37; L. Morris, John, 101; G. Beasley-Murray, John, 16.; C. Barrett, John, 170; J. Bernard, John, 32. Consult K. Wengst, Johannesevangelium, 1:74, who discusses the use of "Schoß" (bosom) in the Old Testament.

J. McHugh, John, 71. He also notes Renè Robert, "Celui," 457–63, who argues similarly.

Contra E. Haenchen, John, 1:121 n. 80, who argues for a hellenistic usage: "in classical usage the phrase would be παρὰ τῷ." C. Barrett, John, 170 agrees with Haenchen, citing Acts 2:5, ἦσαν δὲ εἰς Ἰερουσαλήµ. This instance is clearly implying place where, but it is possible that McHugh is correct. McHugh cites Xenophon Anabasis 1.2.2 as an example: παρῆσαν εἰς Σάρεις (71). Smyth §1686a (Local) has this connotation, but the verbs associated with "into" are all verbs of motion. πάρειµι, though, is difficult, because it can be stative or show motion. Overall, though, McHugh's reasoning is logical in context.

See J. Michaels, John, 81. In Mark, I have argued this is the case as well.

D. Smith, John, 62 also notes the connection with chapter thirteen.

J. R. Michaels, John, 92 postulates, "His place 'right beside the Father'… echoes the assertion at the outset that the Word was 'with God' (v. 1; compare 'with the Father,' 1 Jn 1:2), and it would be easy to infer that this is a glimpse of the postresurrection Jesus, corresponding to the preexistent Jesus of the Gospel's opening verses." He does provide a caveat, commenting on the lack of temporal markers. See also G. Beasley-Murray, John, 16.

B. Schwank, Johannes, 38 explains, "Der Logos ist Fleisch geworden, damit seine Herrlichkeit offenbar werde," but he does not mention the crucifixion. Rather, he speaks of grace and truth becoming available to humanity through the incarnation.

Note: My views of the Johannine Community have shifted slightly since composing this thesis. I have never been persuaded by J. Martyn, History and Theology of the Fourth Gospel or the idea of a “Community” that composed the Johannine literature. H. Mendez’s forthcoming work—The Epistles of John: Origins, Authorship, Purpose—puts the traditional understanding of a historical community into serious question. The argument is exceedingly persuasive, and I do not hold a community view. That said, I do believe 1 John is dependent on the Gospel, and so this discussion is still important. It shows how another author viewed John’s Gospel and then developed themes that were contained in that book.

Original Footnote:

Raymond Brown, Epistles, 14–19 provides a discussion on the relationship between the three Johannine epistles. His commentary presumes the three were written by the same author, but he concedes it cannot be proven. He believes that 1 John was penned by someone other than the Evangelist (35). R. Bultmann, Johannine, 1 holds there were different authors, but "The relationship between 1 John and the Gospel rests on the fact that the author of 1 John had the Gospel before him and was decisively influenced by its language and ideas." Although this cannot be proven, there is clearly a deep relationship between the epistles and the Gospel. Georg Strecker, Johannine, xxxv–xlii provides a discussion of the school, or "Johannine circle," that composed this literature. See also Alan Culpepper, Johannine, 249, who discusses the difference between "active" and "passive" founders.

C. Dodd, Johannine, 110.

G. Strecker, Johannine, 150 writes, "There is a close parallel to this in John 3:16–17, which, in contrast to other mission formulas, agrees with the present passage in its cosmic aspect, in its use of the motif of the love of God, and in its expression of the meaning for salvation as well." R. Schnackenburg, John, 398 asserts this verse is the best commentary, "which agrees with Jn 3:16 in form and content."

A. Brooke, Johannine, 117.

G. Parsenios, First, 115.

Why is ἀγαπητός not used within 1 John? Since the author makes a point to call his recipients "beloved" throughout, he may not have wanted to use the same term for Christ, since he sees him as distinctly different. J. Dunn, Romans, 1:500 makes a similar case in Rom 8:32 where there is a possible Gen 22:16 reference; there, Paul uses ἴδιος instead of ἀγαπητός.

R. Brown, Johannine, 517.

R. Schnackenburg, Johannine, 208 is more in line with Brown, as is R. Bultmann, Johannine, 67.

Note, many have the title ἀγαπητός. It could be that µονογενής developed special associations. It also possible that it just fell out of common use amongst Jewish authors.

In Pseudo-Philo L.A.B. 40, Jephthah's daughter is named—Seila—and she is a willing sacrifice in this text.

G. Strecker, Johannine, 153 shows that ἱλασµός is not found outside of 1 John, though he notes ἱλάσκεσθαι in Luke 18:13; Heb 2:17; ἱλαστήριον in Rom 3:25; Heb 9:5; and ἵλεως in Matt 16:22; Heb 8:12. Overall, the word has the meaning "atoning sacrifice"—cf. LXX Ezek 44:7; Num 5:8; 2 Macc 3:33. Lastly, Strecker states, "In distinction from OT-Jewish or Greek-Hellenistic ideas, according to which human priests were to soothe God's anger through sacrificial actions, the author emphasizes that it is not human action but only the deed of God in sending the Son that has effected atonement" (154).

R. Brown, Johannine, 519. See also 1:7, τὸ αἷµα Ἰησοῦ τοῦ υἱοῦ αὐτοῦ καθαρίζει ἡµᾶς ἀπὸ πάσης ἁµαρτίας. The author clearly has a notion of Christ's death as expiatory. Here again, we see sonship language, which further reveals the motif of a father offering a son as a sacrifice.

See A. Brooke, Johannine, 120.

As A. Brooke, Johannine, 121 notes, this points back to v. 12: the Father has been revealed via the Son. R. Schnackenburg, Johannine, 219 contends, "The Son is called the 'Savior of the world.' This really says the same thing as John 3:17," which is certainly connected with the previous verse.

Verse 18 will not receive its own discussion since its only possible connection is reliant on verse 16.

R. Brown, John, 1:147 even postulates that "the world" my help with the parallel considering Gen 22:18; Sir 44:21; and Jub 18:15.

G. Beasley-Murray, John, 51 postulates a connection, but then states "the event in view is vaster," i.e., the world. A. Köstenberger, Theology, 381–82 postulates soteriological significance in the passage because of its parallels with Genesis 22 and the parable of the tenants.

J. Michaels, John, 203. He also concedes that the image has its limits, which is true. Regardless, it is a strong foundation upon which John constructed his theology of atonement. R. Brown, John, 1:147 remarks, "Just as that death was portrayed under the OT symbol of the serpent in 14–15, so is there seemingly an implicit reference to the OT in the language of 16 [the ‘Aqedah]."

Since there are three different renderings of יחיד, there must have been some connected relationship between all the words used to reflect its meaning.

I have left out µονογενής since it has been discussed previously. See also R. Bultmann, John, 71–73 on how the term has been used.

That is not to imply that no chronological developments occurred with respect to these terms. Although ἀγαπητός does not seem to imply "beloved" based on the LSJ, it certainly did by the time of the New Testament. The implementation of this word within the New Testament will be assessed below.

C. Barrett, John, 216; F. Bruce, John, 41; A. Lincoln, John, 154; A. Köstenberger, Theology, 409; U. von Wahlde, Gospel, 144.

Only(-begotten) Son/Daughter—Hesiod Theog. 426; 449; Op. 376; Herodotus Hist. 2.79; 7.221; Aeschylus Ag. 887; Plato Critias 113s; Diodorus Siculus Bibliotheca Historica 4.73; Dionysius of Halicarnassus Ant. rom. 2.45; 3.1; Jos. Ant. 1.222; 2.181; 5.264; Barius Fables 136; Plutarch De faciae quae in orbe lunae apparet 28; Frat. amor. 6.

Only-begotten World—Plutarch Def. orac. 23; 24; Pseudo-Plutarch Placita Philosophorum 1.5.

Beloved/Only-begotten, though there were other Children—Jos. Ant. 20.20.

Single Entity—Plato Laws 3.691e.

Single Kind—Theophastus De Causis Plantarum 3.10.2.

Unique—Plato Tim. 31b.

Only-begotten God/Son; Referencing God, the Father, & Jesus, the Son—Clement of Alexandria Quis div. 37; Mart. Pol. 20; Eusebius of Caesarea Hist. eccl. 1.2; 7.6; 7.25; 10.4; Basil of Caesarea Epistolae 38; 105; 125; 140; 226; 234; 362; Julian the Emperor Contra Galilaeos 262d; 290d; 333c; 333d.

Seemingly, it is only in earlier commentaries that "only-begotten" is used. See F. Godet, John, 394–95. R. Bultmann, John, 71 n. 2 shows, "The parallelism of its [יחיד] use with ἀγαπητός shows that in such cases µονογ. also ascribes value to that of which it is predicated, which is completely proved by the combination of 'only (son)' and 'first born' Ps. Sal. 18.4; II Esr. 6.58; as does the fact that Israel is described as the 'only son' (see ad loc.)."

I have found only one appearance in the OTP, Συνήχθησαν δὲ πάντες οἱ µοναχοὶ καὶ πᾶς ὁ ἀκούσας· καὶ ἀνεγνώσθη ἐπὶ πάντων ἡ διαθήκη αὕτη·

As I have discussed, I think this distinction is paramount. It would make most sense for Christ, the Son, to be the only-begotten, if God's other children are through adoption. This seems to be the model within the Johannine corpus, since Jesus alone has the descriptor µονογενής and is called God's υἱός. D. Smith, John, 99 agrees, stating, "'Only' in 'only Son' (3:16) again translates the Greek monogenēs, literally 'only begotten,' which becomes important in the later creedal formula 'begotten, not made.'" He provides no further explanation. U. von Wahlde, Gospel, 144, though I disagree on his use of unique, complements this thought: "the repeated stress on the sonship of Jesus as 'unique' was intended to distinguish the sonship of Jesus from that of believers as 'children of God.'"

M. Boismard, Moses, 111 states in reference to these accounts, "In fact, the term ἀγαπητός is often used to designate an only son (Gen 22:2, 12, 16; Amos 8:10; Zech 12:10)."

I have conducted a more extensive exegetical study of these two accounts in Matthew here.

F. Beare, Matthew, 102 notes, "Such a combination of texts is often found in rabbinic teaching, especially in a triple grouping of one sentence from the Law, one from the Prophets, and one from the Writings." Here I argue for Law (Gen 22:2), Prophets (Isa 42:1), and Writings (Ps 2:7). Those who postulate a possible Gen 22:2 allusion, see R. France, Matthew, 123; J. Marcus, Mark, 1:162; E. Boring, Mark, 45; C. Black, Mark, 59; J Levenson, Death, 200ff.

F. Bruce, John, 90 implicitly reflects this, "the best that God had to give, he gave—his only Son, his well-beloved." Consult also A. Köstenberger, Theology, 381.

C. Barrett, John, 180.

I am not insinuating that John knew Josephus. Rather, I am just using this text as an exemplar of how Isaac was described in literature outside of the LXX.

Sacrifice it is not explicitly stated in 1.222, but see 1.224 for Josephus' explanation.

For example, B. Wescott, John, 55; B. Grigsby, Cross; and R. Brown, Gospel.

C. Keener, John, 1:566. K. Wengst, Johannesevangelium, 136–137 concedes a resonance with the ‘Aqedah.

C. Keener, John, 1:414.

If John did not have Genesis 22 in front of him, he could have fabricated an allusion from his memory and failed to remember that Gen 22:2 contained ἀγαπήτος, which could signify that the terms were at least partial synonyms. It could also be the case that John's Genesis text contained µονογενής. It is impossible for us to know for certain.

C. Keener, John, 1:566 also states, "In the context of the Son of Man being 'lifted up' in crucifixion, the aorist ἔδωκεν plainly refers to Jesus' death on the cross, which this passage defines as the ultimate expression of divine love for humanity (Rom 5:5–8)." For a synopsis of the use of δίδωµι as an appeal to the ‘Aqedah in the New Testament, see H. Thyen, Johannesevangelium, 214–215.

J. Levenson, Death, 31.

Isaac is also spoken of as an only (ἴδιος) son, so there may be another lexical connection with the extra-canonical literature. Cf. Irenaeus, Haer. 5.4. J. Dunn, Romans, 1:501 notes that "Even so, a Jew as familiar with OT language as was Paul could hardly have been unaware that he was echoing Gen 22:16…"

For those who support or speculate a connection with Genesis 22, see C. Cranfield, Romans, 208; J. Dunn, Romans, 1:500–1; B. Byrne, Romans, 279. Robert Jewett, Romans, 536–38 provides a detailed discussion of those for and against the allusion. Although skeptics deny the association because the linguistic connections are not strong enough, they fail to combat the thematic as adequately. For example, Jewett cites Halicarnassus Antiq. rom. 5.10.7 to show an instance where φείδοµαι is used parallel to Romans—Brutus asserts that he did not spare his own children (πεισάµενος τέκνων). Although this is intriguing, it was certainly unknown to Paul. If it had been known, we have no proof of it. Regardless, the allusion is subtle but likely on account of the sacrifice of one's only son has a parallel in the Old Testament in Genesis 22.

R. Schnackenburg, John, 1:399 postulates that this verb may have "reminiscence of the expiatory sufferings of the Servant of the Lord (Is 53:6, 12). John only uses the compound verb for Judas's betrayal, his ἔδωκεν is primarily intended to indicate the sending of the Son into the world (cf. v. 17), though this is, of course, the first act of the drama of the Crucifixion, the profoundest mystery of God's love (cf. 1 Jn 4:10)." See also J. McHugh, John, 239.

The connection between John 3:16 and Rom 8:32 has been noted since antiquity; see St. Thomas Aquinas, Commentary, 200. B. Wescott, John, 55 explains, "The word gave, not sent, as in v. 17, brings out the idea of sacrifice and of love shewn by a most precious offering." C. Barrett, John, 216 also postulates a connection between Gen 22:2, 16 and John 3:16 and Rom 8:32, as well as A. J. Bernard, John, 118.

J. McHugh, John, 239.

J. Dunn, Romans, 500 states, "The παρέδωκεν clause certainly echoes a well-established Christian theological understanding of Christ's death (see further on 4:25)." See also F. Godet, John, 394; H. van den Bussche, Jean, 172; J. Becker, Evangelium, 1:145; J. Michaels, John, 202; A. Lincoln, John, 154. U. von Wahlde, Gospel, 145 remarks, "In this verse, Jesus' being 'given' by the Father parallels his 'being lifted up' (previous verse). Therefore, it seems that the 'giving' involves some sort of surrender or giving over."

The Passion predictions are quite telling: 2:21–-22; 3:14–15; 18:21–30; 10:11-21; 12:7; 12:27–36. Also, the lamb of God language reveals this. J. Ramsey Michaels, John, 109 contends concerning 1:29: "The 'servant of the Lord' described in Isaiah 52:13–53:12 is compared to a sheep or a lamb (ὡς πρόβατον… ὡς ἀµνός, 53:7, LXX) in his silence and his willingness to become a sacrifice (this text is quoted and applied to Jesus in Acts 8:32–35; see also 1 Pet 1:19, ὡς ἀµνοῦ… Χριστοῦ)." As for the Suffering Servant, this figure became associated with Isaac; see R. Rosenberg, Jesus, 381–88. 175.

This text is also exemplary based on an observation by Raymond Brown John, 1:389, "Moreover, Miss Guilding, pp. 129–32, has shown that, if her interpretation of the cycle of synagogue readings is correct, all the regular readings on the Sabbath nearest Dedication were concerned with the theme of the sheep and the shepherds. In particular, Ezek xxxiv, which, as we shall see, is the most important single OT background passage for John x, served as the haphtarah or prophetical reading at the general time of Dedication in the second year of the cycle." The Passion account is approaching, which has deep ties with sheep (1:29). The Isaac parallel breaks down a bit in this instance because Christ has moved from the Lamb of God to the Shepherd. Not to side step the issue, but there is a shift in focus. This passage instead accentuates the divine parallel where God is the shepherd in Ezekiel 30 who will take care of his sheep. In a like manner, Christ too "will… seek out [his] sheep, and will… rescue them from all places where they have been scattered on a day of clouds and thick darkness" (Ezek 34:12).

See E. Haenchen, John, 2:49. Haenchen rhetorically states, "We must first inquire how 'to take' (λάβειν) is to be translated: does it mean 'take,' or does it imply 'obtain, receive'?" I will take up this discussion later concerning ch. 19, wherein I connect the linguistic parallels between the Passion narrative and Gen 22. The significance of "to take" could be related to the other ‘Aqedah language that will be discussed later.

John frames the narrative in such a way that people seemed to believe that Jesus was willingly committing suicide. 8:22 contains, "The Jews therefore said, 'Is he going to kill himself because he said, 'Where I am going, you cannot come?'" This plays into the misunderstanding motif expressed throughout the gospel.

Supported by C. Barrett, John, 311.

A. Droge & J. Tabor, Noble, 118. Another theme that could bear weight on this passage is Greco-Roman conceptualizations of a noble death, which eventually seeped into Jewish writings. A. Lincoln, Gospel, 297 states:

That this understanding had already penetrated Jewish literature written in Greek is clearly demonstrated in the way the actions and particularly the deaths of the Maccabean heroes are described in 1, 2 and 4 Maccabees. Two of the major criteria for such actions or deaths are reflected in this verse's formulation about Jesus' death. In order to be praiseworthy or honourable, they should be voluntary and for the sake of others. The notion of choosing a glorious or noble death in preference to life or to bringing shame on others is found in e.g. Plato Menex. 246d; Isocrates, Evag. 3; Thucydides, Hist. 2.42.4, 2.43.4; 2 Macc. 6:19, 28; 7.14, 29 and 4 Macc. 5.23; 11.3; 14.6.

C. Keener, John, 2:814.

Each image has its own context, and not all of them fit together perfectly. The author can seamlessly switch between metaphors. As I stated in a previous note, the Fourth Evangelist has chosen to link Christ with God as a shepherd while also discussing the nature of his death. These concepts are not diametrically opposed, but a slight paradox arises in the images. Regardless, the author wants to convey two aspects of Christ through sheep/shepherding illustrations. This tension can be explained through John's Christology: Christ, the Son, is sacrificed so that the nations might be saved, but Jesus is also one with the father who is the shepherd of all. The conflation of ideas leads to this surface-level paradox.

There is Jewish precedent that connects Passover and the ‘Aqedah, Palestinian Targum on Exod 12:42. Space does not permit a full discussion, but the text is available here: A. Macho, Neophyti 1, 77–79. Peruse R. Le Déaut, Nuit Pascale.

B. Grigsby, Cross, 68 indicates that ἑορτή connotes the Passover ten times in the Gospel. This will not be explored in this paper due to space, but they are further proof that the theme of Passover is paramount to John. This also has resonances with 1 Cor 5:7, for Paul uses the verbal form of this word in his exhortation.

See J. Jeremias, "Πασχα," TDNT 5:896–904 on the various uses of πάσχα.

The temporal framing in the Gospel plays a key role in understanding certain pericopes and running themes. F. Moloney, John, 80 shows: "The Passover 'of the Jews' is mentioned in passages that frame the action (2:13, 23). Feasts are often referred to throughout this Gospel, and there has been considerable discussion over their significance for both the theology and the structure of the Fourth Gospel as a whole."

C. Keener, John, 1:529 points out that this instance shows Jesus to be in line with the Prophets. He states,

By inviting them to 'destroy' the temple of his body (2:19), that is, kill him (cf. 8:28), Jesus stands in the prophetic tradition of an ironic imperative (e.g., Matt 23:32)… John's ἐγείρω thus functions as another Johannine double entendre, misunderstood by interlocutors in the story world while clear to the informed audience.

By destroying the temple, they will have performed the sacrifice that Christ is willing to be. This connection of Temple and Passover is most intriguing because Caiaphas in 11:48 claims it is better for one man to die (Jesus) than have the temple destroyed. Both these pericopes are framed in the temporal setting of Passover. What everyone does not understand, though, is that the Temple (Christ) will rise again. Thus, the irony of misunderstanding plays a role in both accounts.

Consult J. Chanikuzhy, Jesus, 278–80; he contends that the quotation of Ps 69:9 points forward to Jesus' Passion.

One possible thematic parallel that I have found concerns Euripides' Alcestis (only partially because Alcestis does not have the authority to raise herself from the grave). In this play, Alcestis gives up her life so that her husband might be saved. Strikingly, at the end of the drama she has been resurrected. The playwright does not purport by what power she was risen from the dead, but it is one fascinating example of how someone gave up their life so that another, who is honestly unworthy, might be saved, and they too escaped the icy grasp of death.

Consult A. Guilding, Fourth, 58, who also connects the Passover in these accounts with the Passion.

That is not to say the Last Supper is not in mind. Consult C. Koester, Symbolism, 103.

C. Keener, John, 1:680 explains that bread was a common metaphor in Judaism, paganism, and Christianity. He states that the usage here connotes that "Jesus 'sustains life,' which in this Gospel suggests the life of the world to come, available in the present (cf. 3:16, 36; 10:10)." A. Lincoln, John, 228 shows that "in Jewish thought the manna was a source of nourishment and life was seen as symbolizing Torah, so Jesus points out that… the real source of such life in the past was God." The "I am" statements (7 different phraseologies) in the Gospel all seem to have this aspect of imparting life on those who accept Jesus. The way in which Jesus provides life for others is through the giving up of his own life. Jesus is the bread that comes down from heaven, sent by God—or rather given by God—so that the world might be saved. Thus, God is once again supplying life to the people through the bread sent from heaven, but this time it encompasses those outside the Jewish community.