Nota Bene: I will supply a brief explanation of textual criticism in order to follow the argument of this post, but you may wish to read my more extended discussion here, in three parts

All textual variants—that is, alternate readings of a text—are not created equal, and some are of less consequence for understanding a passage (e.g., an alternate spelling, an omission of a word, etc.). Occasionally, though, the differences can impact the meaning of the verse.

In this short analysis, we will look at Rom 8:11 and examine what Paul most likely originally wrote. The variant is not exceedingly major, but it does shift the emphasis of the passage.

A Refresher on Textual Criticism

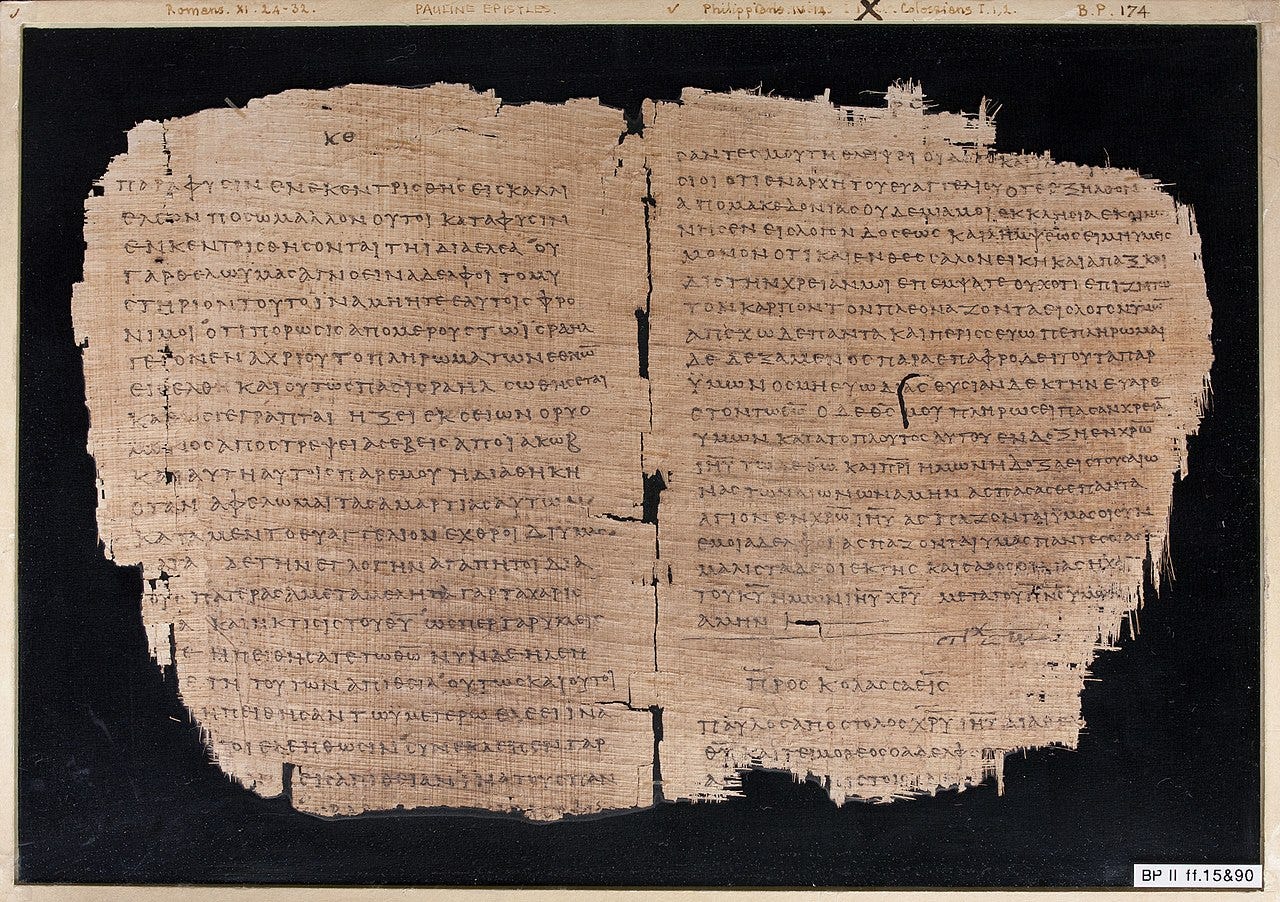

Before we dive into the discussion, let us first establish the criteria that is used for assessing differences in the manuscripts. The goal of the textual critic is to reconstruct—as best as he or she is able—what the author most likely wrote. Since we do not have a single original document from the NT corpus, we must sift through the numerous manuscripts (ms; pl. mss) that we have, categorize them, compare and contrast them, and then determine what was originally put to paper.

Setting this into practice can be daunting since at every step there seems to be exceptions. One must also be familiar with mss, the process of copying, and—almost most importantly—well-versed in Greek grammar. This final requirement eliminates the possibility for most, but here I will try to explain how scholars and textual critics approach a document to determine originality.

Bruce Metzger—one of the foremost textual critics of his day—supplies a good maxim as far as evaluating variant readings: “choose the reading which best explains the origin of the others.”1 As far as discerning the original text, Metzger explains a number of general guidelines:

The textual critic should first look at the apparatus for a given text and generate a list with each variant's supporting witnesses—this will help to see what issue is present and how many principle readings will have to be analyzed.

The second step involves analyzing the external evidence of the text, which contains two parts:

Which mss are the earliest and what are the text-types

The geographical spread of each witness

Familiarize yourself with the various witnesses that can back each reading

Make a judgment of the preferred reading based upon the age of the mss, the geographical spread of the reading, and the text-types to which they belong.

Examine the variant readings in relation to internal evidence—which reading makes the most sense; which is the more difficult reading?

Intrinsic Probability: Does the reading fit the author’s style and usage within the larger context of both the word and, when applicable, to their corpus?

If this seems rather difficult, it should. The process is not as simple as looking at a text and picking the variant you like. If we want to discover what Paul—or any author—originally wrote, we must painstakingly go through this process.

No two textual situations are identical. The above is more like guidelines than rules. The antiquity, geographical spread, and the majority of the mss can side with one reading, and yet that reading may still be wrong. This is why textual criticism is both an art and a science.

A Text Critical Analysis of Romans 8:11

Let us now examine a disputed passage, Rom 8:11. Here, we will be comparing two opposing views:

Bruce Metzger: διὰ τοῦ ἐνοικοῦντος αὐτοῦ πνεύματος, “through his Spirit dwelling...”

Gordon Fee: διὰ τὸ ἐνοικοῦν αὐτοῦ πνεῦμα, “because of his Spirit dwelling...”

The full verse with the commonly accepted, preferred text reads,

εἰ δὲ τὸ πνεῦμα τοῦ ἐγείραντος τὸν Ἰησοῦν ἐκ νεκρῶν οἰκεῖ ἐν ὑμῖν, ὁ ἐγείρας Χριστὸν ἐκ νεκρῶν ζῳοποιήσει καὶ τὰ θνητὰ σώματα ὑμῶν διὰ τοῦ ἐνοικοῦντος αὐτοῦ πνεύματος ἐν ὑμῖν.

But if the Spirit of the one who raised Jesus from the dead dwells in you, the one who raised Christ from the dead will also enliven your (pl.) deathly bodies through his Spirit, the one dwelling in you (pl.).

(N.B. all translations are mine)

Quick Translation Note

“will enliven your deathly bodies”—This will read a little strangely when compared to most translations. Translators smooth this out into better English, but I wanted to focus on the death to life language that permeates this verse.

Death: νεκρῶν (dead, lit. “corpses”); θνητὰ (mortal, “liable to death” [LSJ]—related to θνήσκω “to die”; θάνατος “death”)

Life: ἐγείραντος/ἐγείρας (raise up; resurrection language); ζῳοποιήσει (make alive; bring to life)

I chose to render ζῳοποιήσει as “enliven” so only one word would be used. Other verbs require an added preposition, which can color how one could understand the verb, e.g.,

Give life to the bodies

Make life for the bodies

This may appear to be splitting hairs, but “give life to” and “make life for” do have subtle, connotational differences that may or may not reflect Paul’s intended meaning. Even “give” and “make” can distort how we understand the verb here.

There is but a verb with an accusative object, so I desired to reflect this grammar as best I could.

The text above—bold, italicized—is the subject of our analysis. The variant reading is,

τὸ ἐνοικοῦν αὐτοῦ πνεῦμα | “(because of) his Spirit...”

The case of the noun, “spirit,” and the participle, “dwelling,” differ from the preferred reading; these words have shifted from the genitive to the accusative case. Now this may seem inconsequential, but in reality it changes the meaning of the verse theologically—as argued by Fee who believes the accusative case is original.2 Let us first look at the various witnesses to both readings:3

Many of these sigla will seem nonsensical if you are unfamiliar with textual criticism, but I will explain some of them in this analysis. If you wish to learn more about them, see my second article on Textual Criticism.

The Preferred Reading: “Through the Spirit”

Now, the preferred reading,—the one which has the genitive case—according to Metzger’s commentary on the Greek text, has been awarded a B ranking. To explain this, any major reading in the New Testament with a variant has been awarded a grade, which reflects how confident the Committee is that this particular reading is correct.

At times, the evidence and logic lead the textual critic to be utterly uncertain what was original. In these cases, the ranking would be an F. If they are certain in what they have selected, they grant the reading an A.

So here, the committee was fairly confident in their decision. They claim that the genitive was original because, within the Pauline corpus, Codex Vaticanus (B) is less reliable when it agrees with D and G as you can see in the apparatus above, containing the accusative reading.

Metzger records that the majority of the Committee decided on the use of the genitive because of the combination of text-types: those of the Alexandrian (א A C 81), Palestinian (syrpal Cyril-Jerusalem) and Western (it61? Hippolytus) mss.4

The Variant Reading: “Because of the Spirit”

Conversely, Fee argues for the originality of the accusative reading, relying on the internal and external evidence to support his claim.5

Fee asserts that the combination of text-types establishes his reading because B and 1739 together better represent the Alexandrian text family, and “the preponderance of Western witnesses, early and widespread” support the alternate reading along with various “Palestinian” Fathers (Methodius, Origen, Theodoret).

Fee continues, stating, “the issue therefore must be decided on the grounds of transcriptional probability, since the variation can only have been deliberate, not accidental.”

Additionally, διά, as Fee claims, should take the genitive in the most normal sense when it is used in relation to modifying a verb of resurrection. Since this is the current context, it is most natural that the genitive would have been used.

He claims that because this is what the reader and critic should expect, and—with the accusative being well-attested—it must be the original because it is the “more difficult” reading. That is, it is easier to explain why a scribe would read the accusative, believe it to be an error, and switch it to the genitive.

He furthers his claim, arguing that

One cannot in fact imagine the circumstances in which the very natural genitive would have been changed so early and often to the much less common accusative—especially so in light of 6:4, where the διὰ τῆς δόξης τοῦ πάτρος not only reflects Paul’s ordinary habits but also, by its very difficulty, begs to be changed to the accusative (which would seem to make so much more sense)—yet no one ever did so.

Here, Fee has reasoned the accusative is original due to intrinsic probability. Since the mss evidence is fairly even and it is easier to explain why scribes would change the accusative to the genitive, the accusative must be what was originally written.

Synthesis

It is unlikely that a scribe would change the genitive to the accusative in this context; the accusative, afterall, is a more difficult reading. Also, if one looks at the surrounding context of the verse, it appears more natural to assume Paul intended for the text to read “because of his Spirit.”

This can be seen in Rom 8:10 when Paul writes,

εἰ δὲ Χριστὸς ἐν ὑμῖν, τὸ μὲν σῶμα ⸀νεκρὸν διὰ ἁμαρτίαν τὸ δὲ πνεῦμα ζωὴ διὰ δικαιοσύνην

But if Christ (is) in you (pl.), on the one hand (μέν), the body (is) dead because of sin (διά + acc), but, on the other hand (δὲ), the Spirit is life because of righteousness (διά + acc).

Both of these phrases indicate it is on account of—or, because of—sin and righteousness whether or not one is dead in the body or alive in the spirit, respectively.

Thus, in the following verse,—Rom 8:11—the same logic seems to flow:

But if the Spirit of the one who raised Jesus from the dead dwells in you, the one who raised Christ from the dead will also enliven your (pl.) deathly bodies because of his Spirit, the one dwelling in you (pl.).

Paul here assumes that the Spirit of God dwells within the believer since it is “his Spirit, the one dwelling in you” that will give life to the body.

Now both “through” and “because of” make perfect sense in this context, so one cannot rule out one or the other due to absurdity. But contextually, “because of” appears to hold more weight seeing as previously in verse ten it was because of sin and righteousness that the two results were achieved.

It seems likely that Paul would hold to this formula in both verses 10 and 11: it is on account of X that Y will occur. Due to the irregularity of the accusative in this context, its antiquity in the mss, and the contextual pattern of the surrounding verses, it seems most likely that Fee is correct in asserting that the accusative is the original reading.

The Difference in Meaning and its Significance

Most commentators follow the preferred reading, διά + the genitive: through the Spirit, but many state that the decision is difficult. The textual evidence is strong for both, so they appeal to internal arguments.

That said, a number reflect on the difference in interpretation depending on the genitive (through) or the accusative (because of) reading:

R. Longenecker, The Epistle to the Romans (Eerdmans, 2016), 678,

Internal considerations do not favor one reading over the other. The accusative reading suggests that God will raise the mortal bodies of those possessing the Spirit because the Spirit is essentially a Spirit of life. The genitive reading points to the idea that the Spirit is the direct and personal agent of God’s action in raising bodies.

J. Fitzmyer, S.J., Romans (Yale, 2008), 491–92,

Modern editors of the Greek NT read dia with the gen., which expresses the instrumentality of the Spirit in the resurrection of human beings (so MSS א, A, C, 81). Another reading, strongly attested, is dia with the acc., which would stress the dignity of the Spirit, “because of the Spirit” (so MSS B, D, G, Ψ, and the Vg). In either case “his” refers to Christ (ZBG §210; BDF §31.1), for it is the Spirit as related to the risen Christ that is the vivifying principle.

C. Cranfield, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans (T&T Clark, 2004), 392

Whereas, if the accusative reading were accepted, the meaning would be that the Spirit indwelling Christians now will be a reason for God’s raising them up hereafter, if the genitive is adopted, the meaning is that the spirit who now dwells in them will hereafter be the agent of God in raising them up.

The difference between the two readings can be distilled simply; God will vivify your mortal body

Through the Spirit (agency), or

Because of the Spirit (causal)

The logic of the text seems to imply that both are viable possibilities. But, I do believe Paul intended the accusative reading.

Contra Douglas Moo (The Letter to the Romans [Eerdmans, 2018], 515), who claims,—holding the genitive reading—“And in keeping with Paul’s focus throughout this part of Rom. 8, it is the Spirit who is the instrument by whom God raises the body of the Christian,” I do not reject the idea that Paul would support the agency in this process, that is not the claim he is attempting to make.

Rather, it is a causal statement—that is, the reason why God will animate our mortal bodies—Paul is establishing. Frank Matera (Romans [Baker, 2010], 196) unintentionally makes this claim while defending the genitive position,

It is God the Father who raised Jesus from the dead, the very God who will raise believers from the dead through the life-giving Spirit that dwells in them. Rather than saying that the Spirit raised Christ and will raise those who believe in him, then, Paul affirms that the Spirit who presently dwells in believers is the Spirit of God, the very God who raised Jesus from the dead. It is the presence of this Spirit, which dwells in them, that assures believers that God will revivify their mortal bodies destined for death.

The final statement he makes about “the presence of the Spirit” is a tacit agreement; because this Spirit dwells in us that this is made possible. Indeed, it is through the Spirit that this is achieved, but it is not the logic of the passage.

Consider the logical flow of vv. 10–11

|10| But if Christ (is) in you (pl.), on the one hand (μέν), the body (is) dead because of sin (διά + acc),

but, on the other hand (δὲ), the Spirit is life because of righteousness (διά + acc).

|11| But if the Spirit of the one who raised Jesus from the dead dwells in you, the one who raised Christ from the dead will also enliven your (pl.) deathly bodies because of his Spirit, the one dwelling in you (pl.).

The conjoined conditional statements are meant to explain why something is the case (causal, i.e., explanatory); it is not, instead, a comment on how this is achieved (agency).

Thus, Paul is stating in these two verses,

The body is dead because of sin

The Spirit is life because of righteousness

God will enliven your mortal bodies because of his Spirit (the one dwelling in you)

As Joseph Fitzmyer, S.J. (Romans [Yale, 2008], 491), offers,

Whereas in 7:17 Paul admitted that sin dwelled in unregenerate human beings, now he affirms that the Spirit of God itself dwells in them. This indwelling Spirit is thus the driving force and the source of new vitality for Christian life.

This indwelling Spirit is the reason why this vivification can occur. This is the purpose of these passages, which supports the accusative variant. In the context and reasoning of Romans 8, the reading of διά + the genitive disrupts the flow of explaining the effects of the Spirit.

Conclusion

Although the difference in meaning may seem inconsequential, it is important to remember that the goal of the textual critic is to ascertain what was originally composed. This can have significant implications—e.g., is the Woman Caught in Adultery (John 7:53–8:11) or is the Ending of Mark (16:9–20) original?—or minor impacts, as here.

I do believe that ultimately this distinction is not incredibly impactful, but it does shift the emphasis here in Romans 8. Rather than focusing on the agency of the Spirit, it is an explanation of how our mortal bodies will be made alive—because of the indwelling Spirit, who raised Christ Jesus.

From this short analysis, we can also see that the textual evidence is not always good enough. The geographical spread and the antiquity of the mss on both sides does not definitively determine which was correct. In fact, both readings are easily explainable, so it is no wonder both are present in the ms history. The genitive feels more natural based on previous formulations, and the accusative fits the grammatical flow and formula starting in v. 10.

I stated in the introduction that Textual Criticism is both an art and a science, which this study has illustrated. The science of categorizing and analyzing the mss can only do so much. It takes the creative approach to see that even if the mss evidence is inconclusive, the internal logic of the text and the grammatical formula help the textual critic determine originality.

Finally, this study also shows that the Committee is not always correct. Even if they ranked their assessment with a B, I do believe that the genitive is the less likely reading. Even if most scholars believe the accusative is not as probable, that does not make it the case.

If you have enjoyed reading about a practical look at Textual Criticism and analyzing a portion of Paul’s letter to the Roman, and you wish to read more about the New Testament, would you kindly subscribe?

B. Metzger, The Text of the New Testament (Oxford, 1968), 207.

G. Fee, God's Empowering Presence (Hendrickson, 1994).

The apparatus referenced comes from: B. Aland, The Greek New Testament Fourth Edition (Deutsche Bibelgesellshaft, 2001).

B. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament 2nd ed. (Freiburger Graphische Betriebe, 1994), 456.

All information in this section regarding Gordon Fee’s argument comes from Fee, God’s, 545.