Understanding John 6 as an Early Christian Commentary & Theological Reflection on the Eucharistic Ritual

The Significance of the Developing Practice for a Proper Exegetical Analysis of the Bread from Heaven Discourse

Introduction

John is a theological text, first and foremost. Without establishing this, anything we explore will be difficult to digest. The Gospel is not a historical record. It is not a biography. The text is not meant to be read as a strict retelling of Jesus’ life and ministry.

The proof lies in the divergent nature of the Gospel when compared with the Synoptics narratively and philosophically. The prologue tips the reader off immediately,—we are dealing with a document that is exceedingly dissimilar—and the differing chronology makes this even more apparent.

Clement of Alexandria (ca. 150–215)1 explains,

But John, last of all, conscious that the outward facts had been set forth in the Gospels, was urged on by his disciples, and, divinely moved by the Spirit, composed a spiritual Gospel. (recorded in Eusebius, Eccl. Hist., 6.14.7)

Even the early Christians were aware of the drastically disparate qualities. The Fourth Gospel presents Jesus akin to how Plato developed the life and thought of Socrates. These are theological/philosophical texts wherein the author’s voice erupts from a prominent figure to discuss topics in more detail than what was “historical.”

That is not to say there is no historical data contained in Plato or John, but the impetus for their compositions relates to the writer’s desire to expound on and extrapolate the philosophical/theological thought of another or speak to present concerns through an authoritative figure.

This is not a comment on the Gospel’s historicity;—the events being wrong or contradictory to the Synoptics—rather, my statement is meant to encourage a refocusing on how we read John. This shift in perspective is crucial if we are to read the Gospel as John intended.2 This refocusing is akin to establishing the genre of a work. If we believe a drama to be a comedy, or a comedy to be an historical recounting, then we will misinterpret the author’s purpose.

Nota Bene: If this is troubling to you, or you do not agree with this assessment of the work, that is perfectly fine. My argument and analysis still works, but I believe it is strengthened by reading John as a later Gospel, and he wished to discuss issues that were relevant to his time. For a longer comment, see the note.3

The themes and concerns of John are different from those of the Synoptics,4 which were composed much earlier—potentially 3 decades prior in the case of Mark.

As such, John is a theological text reflecting on the life of Christ, the significance of the incarnation, his sacrifice as the Lamb of God, how the Church was evolving, and how the Church’s thought was developing at the close of the first century—I assume the Gospel was completed ca. 100.

With this in mind, I contend that John’s greatly expanded narrative of the feeding of the 5,000 with the Bread from Heaven discourse is a theological and ritualistic reflection on the significance of the Eucharist.

In order to assess this pericope properly, it is beneficial to see how other New Testament texts have discussed the ritual. The analysis will begin with an examination of 1 Corinthians since Paul directly combats abuses at the Lord’s Table. Next, we will explore the Last Supper recorded in the Synoptics.

The Feeding of the 5,000 and the Bread from Heaven discourse will be analyzed in its own context, while briefly discussing a few other accounts, which will help hone our ritualistic reading.

Early Church Fathers will then be analyzed to see how John’s discussion of the Eucharist fits in this vein of tradition. Since John is a later New Testament text, looking at near contemporaries can reveal how the thought was developing in the late first, early second century. John is not on an island (heh...), and it is critical to situate him in his context.

The article will conclude with a synthesis of all these strands in order to determine the meaning of John’s text on its own while simultaneously contextualizing the development of the Early Christian eucharistic practice and thought.

Early Christian Discussions of the Eucharist

We first need to situate how Christians were discussing eucharistic5 practices and their purpose before we can analyze John’s discussion in chapter 6. As such, our examination will explore our earliest attestation in 1 Corinthians. Were it not for abuses in Corinth, we would be ignorant of Paul’s thought on the Lord’s Supper. Here, we will compare the parallels between reclining at the Lord’s Table and feasting at a table with demons. The ultimate purpose is to show that Paul had a developed understanding of the spiritual significance of participating in the body of Christ.

Second, we will focus briefly on the Words of Institution in the Synoptic Gospels since the actions have their parallel in John 6. This is a partial revelation that our pericope pertains to eucharistic practices. It is no mere coincidence that John has adopted this language for discussing Jesus as the Bread from Heaven.

The Oldest Attestation of the Body & Blood at the Lord’s Supper (1 Corinthians)

Amongst the problems at Corinth,—schism, sexual immorality, meat sacrificed to idols, etc.—Paul felt compelled to comment on the Eucharist.

There are two instances in which Paul directly addressed this for the community, and it is worthwhile to evaluate each one in order to form an understanding of the ritual—practically and theologically.

Participation in the Body & Blood of Christ (1 Cor 10:16–17)

After discussing meat and idols (chapter 8), Paul goes into a discussion of his authority as an apostle (chapter 9). Chapter 10, in turn, relates the discussion to the history of Israel, specifically to the wilderness generation and Moses.

Keep in mind, Paul’s condemnation of idols and meat has not come to its conclusion—Paul injected an excursus on his authority as an apostle. This parallel with the Exodus in 10:1ff. is meant to inform the community of Paul’s understanding of the Eucharist and how it should be contrasted with meat and idols:6

I want you to know, brethren, that our fathers were all under the cloud, and all passed through the sea, and all were baptized (ἐβαπτίσθησαν) into Moses in the cloud and in the sea, and all ate the same supernatural/spiritual (πνευματικὸν) food and all drank the same supernatural/spiritual (πνευματικὸν) drink. (1 Cor 10:1–3)

Paul views these actions as prefigurements: the Hebrews went through the sea, which equates to baptism,7 and they also consumed supernatural bread and drink, which would be the eucharist.8 Even though they participated in these rituals, they still incurred the wrath of God: “Do not be idolaters as some of them were” (v. 7).

Paul parallels the Christian acts of baptism and the eucharist—initiation practices—to the wilderness generation.9 Just like the Israelites experienced baptism and consumed their “Eucharist,” some still slipped into idolatry. So, the Corinthians, too,—they who also were baptized and ate the Eucharist—could fall into this same idolatry, which relates back to chapter 8, as Paul emphasizes in v. 14: “Therefore, my beloved, shun the worship of idols.”

What follows concerns the Lord’s Supper, and it is directly compared with sacrifices to idols:

|16| The cup of blessing which we bless (Τὸ ποτήριον τῆς εὐλογίας ὃ εὐλογοῦμεν), is it not a participation (κοινωνία) in the blood (αἵματος) of Christ? The bread (ἄρτον) which we break (κλῶμεν), is it not a participation (κοινωνία) in the body (σώματος) of Christ? |17| Because there is one bread, we who are many are one body, for we all partake of the one bread.

By drinking from the cup, Paul states that it is directly a participation—a sharing or fellowship—in the blood of Christ.10 By consuming the broken bread, it is a participation in the body of Christ. This is not a symbolic or metaphorical understanding. If the food and drink consumed by the Israelites had been “supernatural/spiritual,”11 how could it not be the case when Early Christians were supping at the Table of the Lord, based upon Paul’s parallel?

From this oblique language, we can surmise that ritually, the community would bless the cup, break the bread,—just as Christ did, which we will see in the Synoptics and later in 1 Corinthians—and then consume. In the partaking of the bread, the community becomes one. Paul does not conceptualize the eating and drinking to be just any standard meal (cp. 1 Cor 11:20). There is a ritual understanding wherein Paul contends some form of supernatural experience is occurring in the ingestion, just as when the Israelites ate their own spiritual, miraculous bread—in their collection and eating, they beheld the glory of the Lord (see Exod 16:10–12). For the Corinthians, there is a synergetic fellowship amongst them as an ecclesial body, while they are simultaneously communing with Christ’s body and blood—all become one.

Paul does not speak directly about his “sacramental theology,” to use an anachronistic phrase. Since the argument concerns meat and idolatry, he does not detail what exactly he believes is happening in this spiritual and real participation in the body of Christ—both meanings intended.

If this parallelism were not foundational, Paul would not then appeal to Israel again:

|18| Consider the people of Israel; are not those who eat the sacrifices partners in the altar (κοινωνοὶ τοῦ θυσιαστηρίου)? |19| What do I imply then? That food offered to idols is anything, or that an idol is anything?

The sacrificial cult and the consumption of the victim are the participation in the altar, per Paul. In turn, the eating and drinking of the body and blood of Christ—whom Paul on some level must consider a sacrifice since he relates Jesus to the paschal lamb (cf. 1 Cor 5:7)—is akin to the eating of the sacrificial victim and the participation in the altar.12 This is not a mere eating of bread and wine; it is a supernatural experience wherein the community becomes united.

Is Paul making a case for a sacrificial offering in the blessing of the cup and the breaking of bread? It may be stretching the metaphor too far; though, he has employed two images: manna from heaven and sacrifice at the altar. Paul essentially states that the bread and wine are spiritual like the manna and water was for the wilderness generation. Then, he relates the partaking of the bread and wine as equivalent to consuming the sacrificial offering as a participation in the altar.

Regardless, it is no wonder why the Early Church adopted the idea that the Eucharist was a sacrifice (See Didache below).13 The analogy is here, and it is certainly not out of the question to extrapolate from this the idea that the body and blood of the Christ—a sacrificial victim for our sins—could be read into the ritual. It is just difficult to say with certainty that it was Paul’s intent. In these verses, again, Paul’s concern is meat and idolatry, not describing the interconnections of the practice and his theology.

Now, the rhetorical question is intriguing (v. 19). It leads the reader to believe that by eating meat sacrificed to idols, the person would then be supernaturally participating in the idol.

Paul rejects this conclusion, but he makes the participation more dire: those behind the idols are demons:14

|20| No, I imply that what pagans sacrifice they offer to demons and not to God. I do not want you to be partners with demons. |21| You cannot drink the cup of the Lord and the cup of demons. You cannot partake of the table of the Lord and the table of demons. |22| Shall we provoke the Lord to jealousy? Are we stronger than he?

Paul does not consider the eating and drinking to be the consumption of ordinary food and drink. And, he rejects the communal rite of participating in the body and blood of Christ if one associates himself with demons—that is, knowingly eating meat sacrificed to idols.

From this succinct parallel, we can already notice that by the time Paul is writing 1 Corinthians (ca. 53/54), he is speaking of the blood and body of Christ in the rite. Keep in mind, the Gospels have not yet been written—Mark is ca. 70.

The Lord’s Supper was already a key feature of early Christian communities, and it was an integral part of their meetings. The text indicates that a supernatural occurrence is happening in the blessing, breaking, and consumption of the bread (and wine), made most explicit in the contrast with the Table of Demons.

Paul later speaks of abuses (ch. 11) of the ceremony, but it is significant that this ancient practice was used as an appeal for unity and concord in the community.

Abusing, Instituting, and Partaking Unworthily of the Lord’s Supper (1 Cor 11:23–29)

Concluding the previous discussion, Paul then provides exceptions and allowances for the sake of conscience for eating meat. The epistle then transitions to a number of topics that Paul wished to address in the community. The second pertains to the Lord’s Supper (11:17–34).

This is logical considering he just used an example from the OT relating to baptism and the eucharist for dealing with idolatry. After already discussing the importance of the ingestion of the body and blood of Christ, Paul was compelled to discuss abuses of this practice.

The compulsion to reprimand the Christian community for how they consumed the Lord’s Supper highlights the importance of the ritual even in the early Church. This could also be argued in 5:6–8:

|6| Your boasting is not good. Do you not know that a little leaven leavens the whole lump? |7| Cleanse out the old leaven that you may be a new lump, as you really are unleavened. For Christ, our paschal lamb (πάσχα), has been sacrificed. |8| Let us, therefore, celebrate the festival (ἑορτάζωμεν), not with the old leaven, the leaven of malice and evil, but with the unleavened bread of sincerity and truth.

“Celebrate the festival” could very well be referencing the partaking at the Lord’s Table.15 Here, the image of Pascha for discussing sin could directly relate to the Eucharist, for one should be without sin—here specifically in the argument, sexual immorality. It is unlikely that this is a reference to a yearly Christian Pascha. The more natural appeal between the two seems to be the routine communal celebration of the Eucharist, which would have been instituted in the Church’s memory at Jesus’s own Last Supper, which occurred at Passover.16

This has a resonance in 11:20–21 where Paul asserts that their division and abuses of the meal disqualifies the ritual:

When you meet together, it is not the Lord’s supper (κυριακὸν δεῖπνον) that you eat. For in eating, each one goes ahead with his own meal, and one is hungry and another is drunk.

The lack of communion at the gathering and sharing in the ritual has led to this condemnation.17 Paul claims that this division and exclusion has invalidated the ritual,18 going so far as to state (v. 22),

Or do you despise the church of God and humiliate those who have nothing?

This is a tacit comment on the significance of sacred space and time in the context of Early Christian ritual.19 There is more occurring here than just the eating and drinking; there is a supernatural reality incorporated in the blessing of the cup and the breaking of the bread.20 If sin is amongst the members, if there is exclusion and abuse, it is “not the Lord’s supper.”

This transitions into potentially early liturgical language, which parallels the Gospels’ records of the words of institution (11:23–26):

|23| For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you, that the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread, |24| and when he had given thanks, he broke it, and said, “This is my body which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me.” |25| In the same way also the cup, after supper, saying, “This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me.” |26| For as often as you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes.

There is no confirmation here that these words were recited in the blessing of the cup and the breaking of bread (cp. 1 Cor 10:16),21 but its near identical phraseology to what we see in the Gospels (esp. Luke) points to an exceedingly early Christian tradition in relation to Eucharistic practices.22

This section then concludes with Corinthian abuses (1 Cor 11:27–34). There are two main points I want to highlight, the warning and the condemnation:

|29| For any one who eats and drinks without discerning the body eats and drinks judgment upon himself. |30| That is why many of you are weak and ill, and some have died (lit. “fallen asleep”).

Paul directly connects unworthy eating of Christ’s flesh and blood as having direct physical complications in the mortal body.23 As I said previously, were the eating and drinking just a symbolic representation of Christ’s Last Supper, how could there then be negative results by consuming improperly?

This concluding paragraph underscores the spiritual nature of the eucharistic ritual that Paul taught in Corinth. The apostle clearly believed that there is a supernatural component that has both spiritual and physical repercussions for partaking, so the members should be prepared to ingest appropriately.

Corinthian Synthesis

Based upon all these threads—Jesus as the paschal sacrifice; the wilderness generation ingesting spiritual bread and drink; participation in the Lord’s body in the Lord’s Supper; partnering with demons at the Table of Demons; physical manifestations of condemnation—there are clear indications that Paul believes that there is a metaphysical or spiritual occurrence happening at the consumption of the bread and the wine. This is not a mere symbolic gesture commemorating Christ.

Paul does not state this plainly. Why would he? He presumes some knowledge of the congregation. But, it is not a giant leap to see the connections. Since the paschal lamb would be eaten after sacrifice,—a necessary component of the ritual (Exod 12:1–28)24—it is natural to see Jesus’s paschal sacrifice as having this connotation developing.

These images of Pascha and the Wilderness Generation work in concert to detail Paul’s view of the significance of the Eucharist, while also partially revealing how he conceptualized it. If the “supernatural” bread in the Wilderness was efficacious and something unique, how much more is it when the believers come together to eat the bread and wine at the Lord’s table to become one?25

It is significant, in turn, to see the eating in the wilderness as a prototype for the Eucharist since Christ is active in that miraculous feeding.26 After saying the people ate their supernatural/spiritual food and drink, Paul states (10:4),

For they drank from the supernatural (πνευματικῆς) Rock which followed them, and the Rock was Christ.

The implication here is that the supernatural sustenance for the Israelites came from Christ, seeing as he was the Rock.27 The parallelism of the wilderness generation and the Corinthians shows that Paul believes there is some kind of pneumatic infusion happening in the ingestion of the physical food.28 Just as Jesus supplied for them in the wilderness, so he provides at the Lord’s Table being present in the bread and wine. The continual celebration at the Lord’s Table is a reenactment of the fulfilled prototype at the Last Supper.

For Paul, there is a spiritual, miraculous reality in the manna. Accordingly, Christ was actually present supplying spiritual, miraculous drink for the wandering generation in the wilderness. Nothing about these statements indicates a metaphorical understanding of Israelite history.

Thus, in the parallel with the Early Church eucharistic rite, when Paul claims that partaking is a participation in or a communion with the body and blood of Christ, he sees it as a reality. The text in no way indicates a metaphorical understanding or just a spiritual occurrence—something real and actual is happening in the breaking of bread and the ingestion of the bread and wine.

If one eats and drinks in an unworthy manner, he is “guilty of profaning the body and blood of the Lord” (11:27). This is a statement of reality; it does not indicate a metaphorical or symbolic abuse. Again, there are real, physical consequences to this desecration.

Finally, we see here the words of institution, the emphasis on bread and the cup, and the ceremonial nature of the practice. Already in the mid 50s, Paul is speaking of the Eucharist as a common and routine practice in the Church where the bread and wine are specifically connected with the body and blood of Christ.

A final thought for reflection: If in the mid-50s, Paul understands a supernatural, miraculous presence of Christ’s body and blood in the ritual, how much more will this develop by the end of the first, beginning of the second century?29

Consuming Christ in The Last Supper (The Synoptic Gospels)

In order to keep the discussion limited to the relevance for John 6, the only analysis of the Last Supper will be the Words of Institution. It is important to see the strands of tradition that exist within the Gospels and Paul:

This will be critical when discussing John 6 and the Eucharistic language contained therein, but for now, I wish to highlight that there are permutations between these four accounts. We can see that there is a genetic relationship, if not dependency, between Paul and Luke. Whereas, Matthew and Mark are more similar.

There is a red thread throughout all four records,—certainly, “this is my body”—but there are two divergent traditions as I noted in the previous paragraph. This reveals that there were (at least) two circulating formulas of the Last Supper. The Gospel of John, though, was written last, and he may have been familiar with each of these. We can pinpoint with some certainty that he knew Matthew and Mark, as we will explore more precisely in John 6.

Note, I did not include John in the chart because there is no Passover Meal in the Fourth Gospel. The chronology of the Synoptics and John differ:

In John, Jesus is the paschal sacrifice, and there is no Passover celebration. This is explicit in 19:14, which is reflected in the chart. Space does not permit a full discussion; see my other posts on this topic.30

I want to establish the chronological differences in the narratives because this helps solidify that John 6 is where the Fourth Evangelist wished to discuss his eucharistic theology. Because he shifted the narrative to focus on Christ as the sacrificial paschal lamb31 on the Day of Preparation, there is no way for this theological point to be made while simultaneously having Jesus and the disciples celebrate the paschal meal—the supping, afterall, occurs after the lamb is slaughtered. The chronology would be nonsensical because Christ would have to die as the sacrificial victim, rise from the dead nearly immediately, and then break bread and drink wine with the disciples for Passover.

As such, John still desired to discuss the significance of the early Christian practice, and he could not do so as the Synoptics did. He relegated the reflection in chapter 6 with the Feeding of the 5,000.32

To Eat Christ’s Flesh in the Bread from Heaven Discourse (John)

This analysis can be best broken up into four parts: the feeding of the 5,000 (6:1–15); the Bread from Heaven discourse (6:22–59); the discomfort and abandonment (6:60–71); and finally a reflection on the Eucharistic significance.

This will not be a line-by-line analysis of the text. Rather, I will focus on the key verses for understanding the eucharistic commentary supplied by John, similar to 1 Corinthians above.

Nota Bene: Since this article is for SubStack, I have not labored to research articles extensively. I have consulted the major commentaries to get the general consensus of this section.

I may continue to update this article as I read more on the subject, but I have worked on this far longer than I had intended for this platform. It is time to just hit publish.

The Feeding of the 5,000 (6:1–15)

Because I believe John knew Mark’s Gospel,33 my previous analysis on this pericope will be assumed—I also hold he is likely familiar with Paul’s epistles. To offer a brief summary of my thoughts on Mark 6:30–44, the narrative is meant to resonate with the Exodus. Moses is constructed as a typology for Jesus who also gave bread to the people in the wilderness.

This is similar, I would argue, to how Paul in 1 Corinthians appealed to the wilderness generation as prototypes of Baptism and the Eucharist.34

John’s telling of this passage is a bit different, but the Bread from Heaven discourse makes it abundantly apparent that he, too, understands the Feeding of the 5,000 to be related to God providing manna in the Wilderness—likely dependent on his understanding of Mark’s account.

As for the temporal framing this narrative in the Fourth Gospel, John specifically mentions the time of year (6:4),

Now the Passover (πάσχα), the feast (ἑορτὴ)35 of the Jews, was at hand.

I stated previously that John’s chronology diverges from the Synoptics, and this is another example of that. In the Synoptic Gospels, Jesus makes but one trip to Jerusalem for Pascha (Passover). Whereas, in John, he journeys to Jerusalem multiple times (2:13ff. [1. Passover]; John 5:1ff. [2. Unnamed Festival]; John 7:1-10, 7:14ff. [3. Feast of Tabernacles]; John 10:22ff. [4. Feast of Dedication, Hanukkah]; 12:12 [5. Passover & Passion]), and numerous Passovers are mentioned (2:13; 6:4; 11:55ff.).

This may seem insignificant, but the season is critical for anticipating a eucharistic interpretation. The author of the Gospel likely presumes his readers are already familiar with a Gospel narrative, so when he mentions Pascha, the mind is meant to connect the narrative with Jesus’s death and resurrection.

The Last Supper, in turn, would also be relevant.36 John is framing a narrative about giving thanks and breaking bread in the temporal context of Jesus’s death. With there being no Passover meal in John, the phraseology here is critical for seeing an echo of the Last Supper—also, compare with the Words of Institution above.

The acts of taking bread, breaking it (not in John 6), blessing/giving thanks, and the distribution all point to a Last Supper and eucharistic appeal,37 which also occurs in 1 Corinthians as we have seen.38 Coupled with the temporal remark of Pascha, it is clear that this miraculous distribution of bread has paschal, Last Supper, and eucharistic intentions.

The narrative ends with a lexical bookend concerning signs:

And a multitude followed him, because they saw the signs (σημεῖα) which he did on those who were diseased. (6:2)

When the people saw the sign (σημεῖον) which he had done, they said, “This is indeed the prophet who is to come into the world!” (6:14)39

Signs40 will play a role in what follows (cp. 3:2), but based upon this miraculous multiplication, it should be noted that the crowd wished to crown him king, so Jesus absconds (6:15).

For our current discussion, this is all that must be established from the feeding account. John intentionally framed the pericope like Mark did: there is an understanding of the Wilderness Generation (as we will definitely see in the Bread from Heaven discourse), and it is a direct reference to the Last Supper and the Eucharist.41

The Bread from Heaven Discourse (6:22–59)

The intervening event is Jesus walking on water (6:16–21),42 which has little relevance for our discussion. But, it is important for establishing a shift in scenery, and it is now the next day.

Others come to this location where the miracle occurred, though, but Jesus is no longer there:

However, boats from Tibe′ri-as came near the place where they ate the bread after the Lord had given thanks (ἔφαγον τὸν ἄρτον εὐχαριστήσαντος τοῦ κυρίου). (6:23)

So that the reader does not miss the context of the expositional dialogue that is to follow, John notes the eating and blessing of the bread, though he adds an intriguing detail: the Lord is who blessed this bread, having given thanks (Eucharist, εὐχαριστήσαντος).43

After this narratorial comment, the people leave for Capernaum since that is where Jesus and the disciples are. The people ask him about his travels, to which Jesus skirts the question44 and begins his discourse on the significance of the previous miraculous feeding and what it points to: the Lord’s Supper and early Eucharistic practices.

The dialogue as we will examine it will be broken into 4 sections:

Consumption of Bread and the Wilderness Generation (vv. 25–34)

I Am the Bread of Life (vv. 35–40)

The Jews Push Back; the Bread of Christ Provides Life (vv. 41–51)

The Eucharistic Connection (vv. 52–59)

The discourse develops and becomes more specific as the dialogue progresses, which Jesus details in the final portion. This lengthy passage is a theological explanation conveyed through disagreement between interlocutors.

As such, It is difficult to untangle the gordian knot in this discourse for numerous reasons.

There is the narrative speaker: Jesus

There is the authorial speaker: John (speaking through Jesus)

There is the narrative audience: those present

There is the ecclesial audience: those hearing the Gospel

Some statements are from Jesus to further the narrative.

Some statements are from the author, which are meant to detail his theology.

Then, there are statements that work on both levels.

Additionally, there is the narrative level of the reading.

There is the authorial intent of said narrative.

Within the authorial reading, there is both the earthly component and the spiritual.

Teasing out the meaning of each remark and the purpose of the exchange is exceedingly vexing.

John 3 can be an excellent model for seeing this because it, in some ways, is easier to untangle. John 3:1–15 is a dialogue between the two characters,—which obviously contains some of John’s meaning—whereas 3:16–21 is a deeper authorial reflection. John 3:12 is a cypher through which these accounts should be read:

If I have told you earthly things and you do not believe, how can you believe if I tell you heavenly things?

In this phrase, John speaks through Jesus stating explicitly that there are two levels of understanding of the passage. He does not negate the earthly or physical understanding, but it ultimately points to the deeper, spiritual meaning.45

John 6, though, has the theological explanation intertwined with the dialogue with the spiritual explanation coming more opaquely in Jesus’s exposition.

A Prototype from the Wilderness Generation (6:25–34)

The foundation of this initial discussion is contingent upon the meanings of signs and work, starting in 6:2, 14, where the narrator states the healing of the sick and the miraculous feeding were “signs.” As the chart below illustrates, when the people inquire about the time of his arrival, Jesus instead starts a discussion with the crowd concerning “signs” and “work”:

Similar to John 3 where Jesus discusses the physical and then the spiritual, in John 6 he does the same. The people who were physically sustained by the ingestion of bread (and fish) now arrive seeking more. Jesus, though, remarks that the food he provided yesterday perishes, but he can supply something better which produces eternal life.

In this introductory section of the dialogue, Jesus immediately states the crowd did not recognize the “signs” (pl.) he previously performed—the healing of the sick in chapter 5 and the multiplication of miraculous bread the day before (6:26). He then tells them not to “work” seeking perishable bread, but they should “work” for food that endures for “eternal life” (6:27). It is what the Son of man will give (6:27b)—indicating it has not yet been supplied.

On the surface, this seems to be a denial of physical bread, but the actual emphasis concerns the duality of the physical and spiritual, which develops through the exchange. But, when will Jesus give this bread? The fulfillment of this promise is a later development, per the discussion; it is at the celebration of the Lord's Supper, in the Eucharistic ritual. Jesus’s comment is not meant to be read as a one time consumption, but rather, at the continual participation in the rite, which will be made clear in what follows. At this point, it is not apparent what is intended.

The crowd, still thinking about a physical meal to fill their bellies now, responds, inquiring what they must perform to be supplied with this bread (6:28). Jesus states simply, “believe in him whom [God] has sent” (6:29).

Clearly, the crowd does not desire to believe in him, for they immediately demand a “sign,”—just as the Wilderness Generation did (e.g., Num 14:11, 20–23; Deut 4:34, 6:22, 7:19. Cp. the Pharisees in Mark 8:11)—while simultaneously asserting Jesus has performed no “work” worthy of their belief (6:30).46 The people should have recognized the Feeding of the 5,000 as a miraculous supply of bread, a sign as John calls it in 6:2, 14.

The wordplay here on “signs” and “works” from both interlocutors is meant to call to mind the Wilderness Generation. This is made explicit when the crowd ironically appeals to the Exodus and the signs the sojourners saw and the works Moses performed (6:31):

Our fathers ate the manna in the wilderness; as it is written, “He gave (ἔδωκεν) them bread from heaven (ἄρτον ἐκ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ) to eat.”

The quasi-quotation is significant because it tethers the passage to the Exodus account. The “signs” and “work” here is the supplying of the manna/bread from heaven, which revealed God’s glory (e.g., Exod 16:4, 15; Ps 78:24; Wis 16:20).47

They attribute the action to Moses, whom they believed provided the heavenly bread. This is critical because it implicitly is a proclamation that Moses performed a “sign” and a “work” in contradistinction to Christ, whom they believe has not. The irony is palpable since 6:1–16 is meant to be read as a fulfillment of the manna from heaven narrative.

Apparently, a good night’s rest makes the crowd’s memory hazy on how they just perceived Christ (6:14–15). Regardless, Jesus reorients their understanding of the Exodus, stating,

|32| Truly, truly, I say to you, it was not Moses who gave you the bread from heaven (τὸν ἄρτον ἐκ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ); my Father gives (δίδωσιν) you the true (ἀληθινόν) bread from heaven (τὸν ἄρτον ἐκ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ τὸν ἀληθινόν). |33| For the bread of God (ἄρτος τοῦ θεοῦ) is that which comes down from heaven, and gives life to the world.

This remark is critical for a number of reasons. First, it strips Moses of his “signs” and “work” and gives it to God. Second, this diminishes the miraculous heavenly bread in the wilderness, for it was not the true bread—it pales in comparison to what the Son of Man will give. And lastly, the source of this “bread of God” is underscored: heaven.

Already, the crowd has committed a number of blunders, illustrating their misunderstanding of the miraculous feeding. When Jesus states in 6:27 that the Son of Man will give bread to the people, this is confusing to them. They desire this sustenance immediately,—implicit in the request for a “sign” and a “work” when coupled with the analogy from Moses—but the bread that he will provide48 comes later.

Thus far, we have a line of tradition concerning bread that has limited fulfillment in the narrative sequence: [Prototype] manna in the wilderness > [Ministerial Fulfillment] the bread for the 5,000.49 Since John explicitly calls this miraculous multiplication a “sign,” it is safe to assume it is a reenactment or partial completion of the prefigured manna from heaven. Yet, it still points forward; there is more yet to give.

As the wilderness ingestion was a prototype for Christ’s miracle, so the miracle is a foreshadowing of the Bread of Life that will be supplied continually in the partaking of the Eucharist. Vv. 25–34 is just the introduction to this explanation, so it establishes the foundation for the discussion.

This narrative exchange is critical for establishing the eucharistic reading. The people (1) do not believe in Jesus; (2) they do not recognize the miraculous signs he has performed; and (3) this will lead to their misunderstanding later in the dialogue—they do not distinguish the difference between the physical and the spiritual correctly.

This is the thesis of John’s theological discussion. Just like God gave the Wilderness Generation manna from heaven to sustain them and show that he is their God, so God has done with Jesus—and gives continually for eternal life. Notice, Jesus does not say the Father “gave”—past tense—or “will give”—future tense—in this discussion (6:32). In the context, there is no present giving. If it were in reference to the miraculous feeding of the 5,000, one would expect an aorist tense. If this is looking forward specifically to the Lord’s Supper, one might expect a future.

Rather, John has slipped into a discussion of what the Eucharist means and the significance of Jesus being the bread there in the ritual. It is bread from heaven which “gives life to the world.” This line works on two levels. On the narrative level, God gives (present tense) his son to redeem the world (e.g., 3:16),50 while simultaneously commenting on the ritual of the Eucharist,—God is giving (present progressive) the Bread from Heaven—which Jesus will make explicit as the dialogue unfolds.51

This is a common ploy in John where Jesus says something that works within the context of the narrative, yet has greater meaning for the audience who is reading the text (e.g., Nicodemus and Baptism in John 3)—Jesus will disclose that he is the “bread of God, which comes down from heaven” (v. 33).52

At this point, the initial dialogue establishes a few key points that will develop throughout the chapter:

The source of Jesus’s origins—Heaven

Seek the bread that does not perish—the Bread of Life, Jesus

Work is required for this heavenly bread—belief in Jesus

A sign is requested—it was provided in the Feeding of the 5,000, a fulfillment of the prototype

The groundwork has been set in order to see the eucharistic significance in what follows, working within the framework of the manna from heaven and the Wilderness Generation prefigurement. The narrative is set so that the misunderstanding plays out just as it did in the Exodus. The people receive their miraculous bread as a sign of God’s faithfulness, yet they do not believe. So here, Jesus has supplied bread and explained its significance for the crowd, yet they, too, will not believe.

This part of the discourse ends with the people making a request, “Lord, give us this bread always” (6:34).53 Though Jesus does not confirm his work or give them an additional sign, they are seemingly convinced. Their discomfort is still to come.

The statement plays off of Jesus’s words similar to Nicodemus. They believe there is a physical bread they will receive that will give them eternal life. The request, then, is both correct and incorrect simultaneously.

Jesus as the Bread of Life (6:35–40)

The conversation now transitions to Jesus explaining what exactly that bread is. Jesus replies to their request, saying (6:35):

I am the bread of life (ἄρτος τῆς ζωῆς); he who comes to me shall not hunger, and he who believes in me shall never thirst.

This sets up a perceived metaphorical reading since Jesus is not bread. Most commentators remark on the parallelism with Sir 24:21, but there is more at play here than a reference to God’s Word and wisdom.54 He continues to expound on those who believe in him and who sent him down from heaven (6:36).

But I said to you that you have seen me and yet do not believe.

This is a subtle response to their demand for a sign and works. The crowd has witnessed him perform these deeds like Moses/God in the wilderness, and yet they do not believe in him. The second major statement for our discussion comes in 6:38,

For I have come down from heaven (καταβέβηκα ἀπὸ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ), not to do my own will, but the will of him who sent me.

Jesus declares that his source is from heaven, just like the miraculous bread in the wilderness that the people referenced at the beginning of the dialogue. In these two statements, Jesus has directly addressed their request, while simultaneously establishing himself as the bread from heaven.

This portion reads like a metaphorical comparison—Jesus is the bread of life that came down from heaven just as God sent down manna from heaven.55 In contrast, though, Jesus’s mission will sustain the people in a way that the manna could not.

What is required for this eternal life? Belief in the Son—repetition of 6:29.

This paragraph, though, is transitional. It is a description of what is required in order to receive this eternal life on the spiritual level, which the people present will misunderstand. They believe he is speaking of actual bread which will provide actual results in the physical world. Jesus has transitioned to a discussion of the spiritual reality of who he is and what the bread’s source is—from heaven.

But, does this disqualify a literal reading? Is the Bread from Heaven discourse meant to be read only on this metaphorical level? As I will argue in what follows, there is a both-and reading in the text. The metaphorical speaks to the prototype in the Exodus to convey a spiritual understanding of the consumption of bread, but John, too, has an idea that the bread is to be literally consumed, which is enacted in the Eucharistic practice.56

Push Back and the Failure of the Prototypical Bread (6:41–51)

Confrontation and discord follows this description. The people are perplexed due to Jesus’ ambiguity and refusal to provide a direct answer. They embrace their role as the prefigured characters—the Wilderness Generation—with their response,

The Jews (Ἰουδαῖοι) then murmured (ἐγόγγυζον) at him, because he said, “I am the bread which came down from heaven.”

This is the first time they have been identified as “Jews,” which seems appropriate for the context. John wants the crowd identified correctly, since they parallel the wandering generation (Exod 16:7–8):

|7| ...and in the morning you shall see the glory of the Lord (τὴν δόξαν κυρίου), because he has heard your murmurings (γογγυσμὸν) against the Lord. For what are we, that you murmur (διαγογγύζετε) against us?” |8| And Moses said, “When the Lord gives (διδόναι) you in the evening flesh to eat and in the morning bread to the full (ἄρτους... εἰς πλησμονὴν), because the Lord has heard your murmurings (γογγυσμὸν) which you murmur (διαγογγύζετε) against him—what are we? Your murmurings (γογγυσμὸς) are not against us but against the Lord.”

Narratively, the people are grumbling and demanding sustenance just as the people did against Moses and the Lord in the wilderness.57 Their appeal to this narrative is meant to be ironic, since John 6 is playing off of their total and complete misunderstanding of the miracle Jesus performed. This prefigured Exodus account is critical because it underscores the physical reality of Jesus as the bread from heaven.

This pericope is developing and playing out just like in Exodus 16. The Wilderness Generation, just like the Jews in John 6, grumble against the Lord, they have seen signs and wonders, and yet they fail to believe.

Additionally, 1 Cor 10:10 plays off this same lexical connection,

nor [murmur(γογγύζετε)], as some of them [murmured (ἐγόγγυσαν)] and were destroyed by the Destroyer

Considering the close proximity to a discussion of the Eucharist and the Israelites in 1 Corinthians, this shows at the very least a genetic connection between John and Paul. Is John aware of this epistle? That is difficult to say with certainty, but it does establish minimally a similar vein of thought.

As for the connection with the Exodus, this verb is used routinely to display the Wilderness Generation’s discontent for God and putting him to the test (Exod 16:2, 7–9, 12; Num 11:1; 14:2, 27, 29, 36; 16:11–35; 17:6).58 This further supports the Exodus prototype lurking underneath John 6.

On a narrative level, though, the crowd’s frustration is warranted. When they initially arrive and inquire about when he arrived, Jesus does not answer their question. When they ask for a sign, Jesus instead remarks that God did those works, not Moses. When they make a request for this bread that provides eternal life, Jesus states that he is that bread and they must believe in him.

Their disgruntled reaction manifests with doubt since they know Jesus’s earthly origins,—he is the son of Mary and Joseph (6:42)—so how can he be from heaven? Jesus calls them out as the Wilderness Generation—“Do not murmur (γογγύζετε) among yourselves (6:43)—and responds by restating that he is the bread of life, and they must believe (6:47–48).

Jesus then contrasts the bread from heaven the Israelites received, which led to death, with his, which leads to immortality (6:48–51),

|48| I am the bread of life. |49| Your fathers ate the manna in the wilderness, and they died. |50| This is the bread which comes down from heaven, that a man may eat of it and not die. |51| I am the living bread which came down from heaven (ὁ ζῶν ὁ ἐκ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ); if any one eats of this bread, he will live for ever; and the bread which I shall give (δώσω, fut.) for the life of the world is my flesh (σάρξ μού).”

This segment of the dialogue restates that Jesus is the bread of life and Jesus’s origins: heaven. This is the first of two (6:58) contrasts between the Wilderness Generation’s bread and his own, and Jesus states one must eat this bread in order to taste eternal life. It still resembles a metaphor, but this cannot be the proper reading considering what follows.59

The image heightens and becomes more incarnational as the narrative progresses:

Miraculous multiplication of bread (6:1–16) > Fulfilled prototype reference of the wilderness miracle (6:31) > I am the Bread of Life and belief (6:35) > I am the Bread of Life, eat this Bread for eternal life (6:51) > Eat my flesh and drink my blood or there is no life in you (6:53–56)

Jesus ramps up how explicit the explanation is as the exposition evolves.

We must remember that this is a post-resurrection reflection; it has been nearly 70 years since Christ’s death.60 As such, we are dealing with a new generation of believers, and the apostolic age is nearing its end. The Eucharist is an established practice in the Church, and the rite has been celebrated for nearly as long.

1 Corinthians attests to this. To believe there were no theological or conceptual developments between the 50s and the early 2c. would be ridiculous. This dialogue from Jesus’s mouth is further reflection from the author, which he will make even more explicit in the following section.

The final line spoken, that the bread Jesus will give (fut.) for the world is his flesh. There is a double meaning here again as previously. The narrative level reading is akin to 3:16, yet calling the bread his flesh is pointing to the audience level reading, which corresponds to the Eucharist.61 This line is meant to connect the Eucharist explicitly with his sacrificial death at the end of the Gospel.

Here, he is commenting both on the origins of Jesus and the importance of the eucharistic rite.62 It is a direct comparison to the Wilderness Generation as Paul did in 1 Corinthians 10. John, though, expounds on the necessity of believing in who Jesus is, that he gave his flesh for the redemption of the world.

It is in the Eucharist, the true bread from heaven, that Christians ingest so that they will not die. This, again, is working on both a physical and a spiritual level. The people will eat this physical bread, and they will physically die. The statement, “if anyone eats of this bread, he will live forever,” is a reflection on the physical necessity of consuming the bread in the Eucharist in order to receive the spiritual reality of eternal life after the flesh has died.63

This is the duality of the ritual. A physical consumption for a spiritual sustenance, which leads to immortality.

The final line, “the bread which I shall give for the life of the world is my flesh,” is an appeal to the physical reality that Jesus will die. The bread is functioning on both a metaphorical level and a narratively real level.64

This is made explicit in Jesus’s final words of the discourse.

Jesus is the Eucharist (6:52–59)

As shown in the Feeding of the 5,000 account, Jesus intended a Last Supper parallel with Jesus taking the bread, giving thanks, and distributing it. This following discourse, in turn, is expounding on the significance of the continued eucharistic ritual in the Church.

The people illustrate this in their failure to understand by asking, “How can this man give us his flesh (σάρκα) to eat?” (v. 52). The reader is intended to understand this as a commentary on the Last Supper. John is taking the idea of “this is my body” (etc.) as the foundation of the dialogue—an anachronism since the Passover meal has not (and will not) occur in the Fourth Gospel.65 This dialogue exists outside of narrative time, though; it is a theological commentary outside of the story.66

Having this in mind, when we read Jesus expounding on the bread being Jesus’s flesh, this is John’s voice coming through.

He has Jesus state,

|53| Truly, truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh (φάγητε τὴν σάρκα) of the Son of man and drink his blood (αἷμα), you have no life in you; |54| he who eats my flesh (ὁ τρώγων μου τὴν σάρκα) and drinks my blood (αἷμα) has eternal life, and I will raise him up at the last day.

|55| For my flesh (σάρξ) is food (βρῶσις) indeed, and my blood (αἷμά) is drink (πόσις) indeed. |56| He who [chews (τρώγων)] my flesh (σάρκα) and drinks my blood (αἷμα) abides in me, and I in him. |57| As the living Father sent me, and I live because of the Father, so he who [chews (τρώγω)] me will live because of me. |58| This is the bread (ἄρτος) which came down from heaven (ἐξ οὐρανοῦ), not such as the fathers ate (ἔφαγον) and died; he who [chews (τρώγων)] this bread (ἄρτον) will live for ever.

John now utilizes an exaggerated term—τρώγων, “to chew”— to emphasize the reality of ingesting his body and blood, a more graphic image of mastication.67 Throughout chapter 6, ἐσθίω (aor. inf. φαγεῖν) has been used, so the lexical shift is significant.68 John intentionally employed word variation to underscore the necessity of this ritual action. It is no coincidence that the verb for eating bread by the crowd and the Wilderness Generation is ἐσθίω, and now when Jesus speaks about eating his flesh, John has employed τρώγω—including “bread” in vs. 58, which is clearly paralleled with Christ’s flesh and distinguished from the wilderness bread.69 This word in chapter 6 is used only in association with consuming the body of Christ.

This highlights the need and the necessity of participating in the Eucharist for eternal life. This is not a metaphor; this is not a symbol. It is an emphasis on the reality of consuming the body and blood of Jesus in the eucharistic rite.70 This bread comes down from heaven and provides eternal life, which is contrasted with that of the Wilderness Generation. If an understanding of actual consumption is not intended, the comparison is rendered nonsensical.

Outside of John 6, τρώγω appears one other place, at the foot washing, the non-paschal Last Supper (13:18),

I am not speaking of you all; I know whom I have chosen; it is that the scripture may be fulfilled, ‘He who [chewed (τρώγων)] my bread has lifted his heel against me.’

This is an intentional alteration of Ps 40:10 LXX (Ps 41:9 MT),

Indeed, the person at peace with me, in whom I hoped,/ he who would eat of my bread (ἐσθίων ἄρτους μου), magnified trickery against me. (NETS, following the LXX, not MT)

There is no specific mention of bread being ingested at John’s Last Supper. A “supper” (v. 2, δείπνου γινομένου) is referenced, which implies eating, but there is no mention of actual bread, which is a significant omission. The occurrence of “chewing bread” here is crucial because this final meal is meant to resonate subtly with chapter 6, and John shifted the verb in Psalm 40 LXX in order to achieve this. The Evangelist considered the Passover of the Synoptics as the institution of the Eucharist, and he uses an internal lexical echo to reveal this—the discussion is the meaning of “this is my body.” His eucharistic commentary could not take place in chapter 13 as I previously discussed, so this verbal parallel performed the heavy lifting.

Now, the extrapolation and contrast back in John 6 accentuate the failures of the prototype. The fathers ate the miraculous bread in the Wilderness, yet they died a physical death. The people at the feeding of the 5,000 witnessed a sign, but that miraculous bread will not save them from death—it was to reveal the glory of the Lord and save their earthly lives, akin to Exod 16:7–8.

Since John believes in some supernatural reality occurring in the Eucharist, as he also does in baptism, so you are abiding (Pauline, “participating”) in Christ when you consume the bread and wine at the Lord’s Table. This final paragraph is an understanding of a spiritual reality that Jesus is actually present in the bread and wine in the eucharistic rite, and it is meant to sustain the life of the believer.

This, obviously, is not a remark on a physical eternal life. John has an understanding of all Christians sustaining themselves through the ritual so that they may attain immortality after death. This paradox is a common understanding within Christianity: you must die to live (e.g., in baptism Rom 6:3–5).

If this leaves the reader unconvinced, John employed narrative parallelism to drive this point home. The inquiry from the Jews directly parallels the misunderstanding of Nicodemus.

The syntactic and narrative styles are nearly identical. If one reads that there is a baptismal component meant in John 3, yet one denies a eucharistic reading in John 6, the reader fails to appreciate the Johannine method of discussing the two ecclesial practices in his Gospel.

Although John 6 is a more protracted account, the parallels are striking.

In both of these accounts, Jesus speaks of “earthly things” (3:12), yet the interlocutors do not comprehend, so they fail to realize the “heavenly things” that accompany the act. They take him too literally, which reveals their incomprehension. Is the Eucharist the consumption of Christ’s flesh to John? Yes and no.

Being born initially, for comparison, is an action “of the flesh,” just like eating to sustain our mortal life is an action “of the flesh.” In contrast, the immersion in water—a physical reality—is more than the washing of dirt off the body (cp. 1 Peter 3:21); it is regenerative (Titus 3:5)—it is an act of being “born of the Spirit,” to use Johannine language. So, too, the ingestion of bread and wine—a physical reality—is more than a consumption of bread; it is an act of eating bread from heaven, the flesh of Christ.71 Both rituals are spiritual in nature, distributed through a physical medium.

The Gospel of John is reflecting on these early Christian rites and the “heavenly” or spiritual reality that is happening in the “earthly” or physical practice. The dual nature of the early Christian rites is apparent. There is both the earthly use of water and bread in order to experience spiritual “re-birth” and heavenly “eating” of Christ’s flesh.

John closes the discussion with another contrast with the prototype,

This is the bread which came down from heaven, not such as the fathers ate and died; he who eats this bread will live for ever...

The prefigured narrative in Exodus only gave half of the equation: physical sustenance. The fulfillment of this account on a narrative level in John happened at the feeding of the 5,000, but it also only provided the first half of the equation: physical sustenance.

The reception of the bread will be received fully on a spiritual level at the Lord’s Table. Nowhere in this account has the Son of Man given this bread—and, it is not looking purely at the cross; that is only a partial narrative completion, which fails to resolve the resounding chord of consuming flesh and blood—the death of Christ in no way fulfills this ingestion.

There is no Last Supper in the Gospel for Jesus to distribute this bread in the future, as one would think the narrative would demand. Rather, the Son of Man will give this bread later—and continually—in the eucharistic rite, which will provide life eternal.72

John, like Paul, believed there is more to the Eucharist than just the ingestion of food. There is an incorporation with Christ (“participation”/“abiding”) on a spiritual level, and it is more than the physical reality of eating bread and drinking wine.73

Discomfort & Abandonment from some of Jesus’s Followers (6:60–71)

The misunderstanding continues after Jesus is finished conversing with the Jews. Now, his own disciples—not the 12—comment on the difficulty of his words (v. 60),

This is a hard saying; who can listen to it?

Jesus perceives their discontent—“knowing in himself that his disciples murmured (γογγύζουσιν) at it”—just like the previous crowd and the Wilderness Generation, and he responds similarly to them as he did Nicodemus about the spiritual and the physical (vv. 61–64),

|61| Do you take offense at this? |62| Then what if you were to see the Son of man ascending where he was before? |63| It is the spirit that gives life, the flesh is of no avail; the words that I have spoken to you are spirit and life. |64| But there are some of you that do not believe.

The ascension of the Son of Man is a spiritual or heavenly perspective the crowd is not yet ready to comprehend. He reaffirms what he did with Nicodemus of the spiritual necessity of the acts. The “flesh is of no avail” statement is meant to highlight that the physical components are not what provides the heavenly sustenance. This is not a denial of their importance in the act. Rather, it is a comment on the deeper meaning of these rituals: there is a synergetic relationship between the physical and the spiritual. Belief is required; it is that necessary work.

How can one make sense of 6:55 in light of v. 63 if we are to deny the physical completely?—the statements appear diametrically opposed:

For my flesh is true/real/genuine (ἀληθής) food, and my blood is true/real/genuine (ἀληθής) drink.

The text is not gnostic, nor is it docetic. John does not reject physical reality. Rather, he highlights the importance of the spiritual, which is of utmost significance for his theology. Jesus’s kingdom is not of this world (18:36),—though, he is crowned “king” at the end of the narrative (19:20)—and his source is from above (3:31–36; 8:21–30)—though, he does have an earthly mother (6:42).

If the flesh were to be discarded and of no value, why would Jesus in his resurrected form have a fleshly body with his pre-resurrection wounds? The confirmation of the resurrection for Thomas is a physical reality (20:27–28):

|27| “Put your finger here, and see my hands; and put out your hand, and place it in my side; do not be faithless, but believing.” |28| Thomas answered him, “My Lord and my God!”

This confirmation comes from touching the wounds in the flesh of Jesus’s body. If the spirit is all that matters, the emphasis on the wounds and flesh of Christ in this instance would be nonsensical. The flesh reassures Thomas and brings about faith and believing.74 At the end of the Gospel, Jesus is resurrected in the flesh.

Additionally, at the outset of the Gospel, the Word became flesh (σὰρξ) and dwelt among us (1:14), and, as such, John’s cosmology was impacted by his understanding of the incarnation—John 1 sets the stage. It is not the Spirit that reveals God to humanity. Rather, it is contingent upon the incarnation (1:18),

No one has ever seen God; the only Son, who is in the bosom of the Father, he has made him known.

So, by extension, John’s sacramental—ritualistic—thought developed in this light.

There is a false dichotomy imposed by the reader to assume flesh is bad and spirit is good.

When read in light of 6:32,—“but my Father is giving to you the true (ἀληθινόν) bread from heaven”—if Jesus is the true bread from heaven there, and he claims his flesh is “true” food in 6:55, should we not take them both as literal? Jesus is the “true” bread from heaven, and his flesh is “true” food.75

John 6 is a theological/sacramental explanation of what is meant by “this is my body.”

Were this practice/teaching purely metaphorical, how could anyone be scandalized? It is the physical and spiritual reality in the eucharistic rite that John is discussing. “Flesh” is nothing—the ingestion of normal food—because it does not bring about eternal life. You must consume the “true flesh” of Christ in the ritual—bread that leads to immortality.

It is difficult for his disciples to comprehend, and so, they do not appreciate the reality of the transformative nature of the Eucharist, which causes them to fall away and leave. Because they do not believe in Jesus, they do not understand the spiritual quality of the ingesting of his physical flesh. It is by the Father this truth is revealed to them through Christ.

The Eucharistic Significance of John 6

Understanding the ambiguity of Jesus’s words in John is commonly dualistic.

As John 3 was a reflection on the significance and purpose of Baptism, Jesus plays on ambiguous wording: born from above/again, both of water and spirit. Nicodemus is both wrong and correct. Jesus does mean one must be born again physically—via water—and born from above.

This is a call to ritualistic rebirth: baptism, which includes a spiritual birthing—one from above. To require the reader to pick between one or the other betrays John’s commentary and theological reflection on baptism.

Similarly, later in John 8, when Jesus discusses departing from this world, the people ask, “Will he kill himself, since he says, ‘Where I am going, you cannot come’?” (v. 22). The answer is no, but also yes.

Jesus is not committing suicide, as the question seems to imply, but he certainly is a willing participant in the crucifixion and readily accepts his fate—as I have written elsewhere. In turn, Jesus does end up “kill[ing] himself,” but those present do not understand the how or the why—akin to Nicodemus. They are focused on the physical literalism of Jesus’s statement, yet fail to see the spiritual significance, as Jesus says (v. 23), “You are from below, I am from above; you are of this world, I am not of this world.”

Here in John 6, the people ask, “How can this man give us his flesh to eat?”—believing they are supposed to eat him literally. Does Jesus intend for them to eat his actual flesh here in the narrative? No, but also yes. The ritual of the Eucharist very early on as we saw in 1 Corinthians 10 and the Synoptic Gospels conceptualized the bread and wine as the body and blood of Jesus. This discourse is a contemplation on the spiritual reality of these statements. It is a physical and spiritual reality. The bread is both bread and Christ’s flesh.

Jesus plays off of questions of misunderstanding to show the people are correct while simultaneously incorrect. As is the ritual aspect of John 3 prominent, so, too, here is the Eucharist centerfold, as it is in Mark.

Jesus doubled down in 6:53–58, as we explored. The analogy with the wilderness generation feasting upon manna only makes sense if Jesus is intending an actual consumption of bread. This text is a theological reflection on what the Eucharist is: it is the manna from heaven made manifest in the flesh of Christ. It is in the Eucharistic rite that early Christians believed they were fulfilling by devouring the body and blood of the Lord.

Now, is it too much to impose on John a fully developed medieval understanding of Transubstantiation from Thomas Aquinas? Well, yes. Exegetically that would be an anachronistic reading.

But, as we have explored elsewhere in Scripture, the germ is there for how this sacramental thought developed. The ritual in the Early Church was already conceptualizing a spiritual reality in the physical bread and wine, though, which we can see vividly in how Church Fathers described this practice.

Early Church Discourse on the Eucharist

There will be less of an argument presented in this section of the article. Rather, the point of this section is to be a resource bank for how the Early Church talked about the Eucharist in general.

The purpose of these quotations is to show how thought was developing in the nascent church and how John fits within this context.

Didache, late first, early second century (compilation as late as 150)

“But let no one eat or drink of your Eucharist (εὐχαριστίας) except those who have been baptized into the name of the Lord, for the Lord has also spoken concerning this: “Do not give what is holy to dogs.’” (9.5)

“(1) On the Lord’s own day gather together and break bread (κλάσατε ἄρτον) and give thanks (εὐχαριστήσατε), having first confessed your sins so that your sacrifice may be pure. (2) But let no one who has a quarrel with a companion join you until they have been reconciled, so that your sacrifice may not be defiled. (3) For this is the sacrifice concerning which the Lord said, ‘In every place and time offer me a pure sacrifice, for I am a great king, says the Lord, and my name is marvelous among the nations.’” (14:1–3)

Ignatius of Antioch, d. ca. 108–117

“All of you, individually and collectively, gather together in grace, by name, in one faith and one Jesus Christ, who physically was a descendant of David, who is Son of Man and Son of God, in order that you may obey the bishop and the council of presbyters with an undisturbed mind, breaking one bread (ἕνα ἄρτον κλῶντες), which is the medicine of immortality, the antidote we take in order not to die but to live forever in Jesus Christ.” (Ephesians 20.2)

“Take care, therefore, to participate in one Eucharist (εὐχαριστίᾳ) (for there is one flesh [σὰρξ] of our Lord Jesus Christ, and one cup that leads to unity through his blood [αἵματος]; there is one altar, just as there is one bishop, together with the council of presbyters and the deacons, my fellow servants), in order that whatever you do, you do in accordance with God.” (Philadelphians 4.1)

“[The Docetists] abstain from Eucharist (εὐχαριστίας) and prayer because they refuse to acknowledge that the Eucharist (εὐχαριστίαν) is the flesh (σάρκα) of our savior Jesus Christ, which suffered for our sins and which the Father by his goodness raised up.” (Smyrnaeans 6.2)

Irenaeus of Lyons, ca. 130–202

“When, therefore, the mingled cup and the manufactured bread receives the Word of God... the Eucharist becomes the body and blood of Christ... For as bread from the earth, receiving the invocation of God is no longer common bread but a Eucharist composed of two things, both an earthly and a heavenly one, so also our bodies, partaking of the Eucharist, are no longer corruptible, having the hope of eternal resurrection.” (Adversus Haereses, 4.18.5)

Clement of Alexandria, ca. 150–215

“The blood of the Lord is twofold. For there is the blood of His flesh, by which we are redeemed from corruption; and the spiritual, that by which we are anointed. And to drink the blood of Jesus, is to become partaker of the Lord’s immortality; the Spirit being the energetic principle of the Word, as the blood is of the flesh.” (Paedagogus 2.2.19)

Two things I would like to highlight concerning early eucharistic thought is the practice as a sacrifice (Didache) and the understanding that the ritual includes the flesh of Christ (Ignatius).76 These two documents are near contemporaries of John’s Gospel, and their authors have a similar conceptualization of what we have discussed.

Though, I am hesitant to say for certain that Paul was working within a framework of a eucharistic sacrifice based upon the paschal lamb language, this idea emerged early, as seen in the Didache. If it were not Paul’s belief, the Early Church adopted this language shortly after his epistles were composed. We see here also the importance of breaking bread and giving thanks that we analyzed in Paul, the Synoptics, and John.

As for the presence of Jesus’s flesh in the ritual, the quotations from Ignatius speak for themselves. There is this idea of unity in the act of partaking, which is genetically related to the “participation” in 1 Corinthians and “abiding” in John. If these texts are not all dependent upon each other,—I believe this is a developing vein of thought within these writings—they are independent strands of thought that are certainly congruent with each other.

We see again the importance of breaking bread in Ignatius (Ephesians), which solidifies the importance of the act in the Eucharist. This idea exists in Luke-Acts, which illuminates our understanding of practices in the Early Church. Acts 2:42 records,

And they devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and fellowship, to the breaking of bread (κλάσει τοῦ ἄρτου) and the prayers.

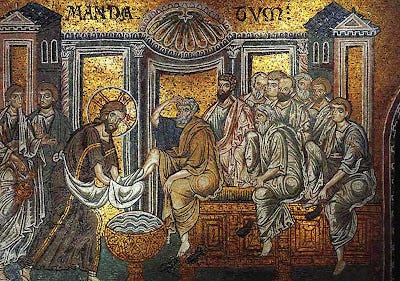

Now, the “breaking of bread” may seem only a subtle allusion to the Lord’s Supper/Eucharist, the Road to Emmaus account solidifies this. Here, Jesus is walking with two unnamed disciples who do not recognize the risen Lord, but it is at the breaking of bread, a clear echo from the Last Supper, that they realize just who is with them:

|30| When he [was reclining] at table (κατακλιθῆναι) with them, he took (λαβὼν) the bread (ἄρτον) and blessed (εὐλόγησεν), and broke (κλάσας) it, and gave (ἐπεδίδου) it to them. |31| And their eyes were opened and they recognized him; and he vanished out of their sight.” (Luke 24:30–31)

These early Christian rituals did not spring from nothing. The Early Church believed a synergetic relationship existed between the earthly elements and the spirit that was occurring in the breaking, blessing, and consumption of the bread.

Synthesis & Conclusion

There is, ultimately, a confluence of themes and images in John 6. The NT authors saw a connection between the paschal lamb and the manna from heaven narrative when discussing the importance of the Last Supper—both were prototypes for the Christian practice. It is difficult not to see the idea of sacrifice and consumption in the Last Supper and the Early Christian rite.

Were these ideas explicitly in the minds of Paul, the Synoptic Evangelists, and John? That is difficult to say with certainty, but there were developments happening in the first decades leading up to the beginning of the 2c. The germ of this eucharistic thought can be seen in 1 Corinthians, and the development can be witnessed in the Synoptics, and a fuller, fleshed out belief can be read in John.

The importance of this discussion is to show that this concept of Christ’s presence in the bread and wine resides in Scripture. Expecting an exact and fully developed Eucharistic theology as we understand it today in the 1st or 2nd c. is preposterous. The conceptualization of the metaphysical reality in this rite grew as the Church practiced and reflected on the Sacrament.

But, what we can say, is that even in Paul, there is a pneumatic infusion of some kind in his sacramental theology. Paul certainly does not believe in a metaphorical remembrance, and John absolutely does not hold this thought.

There was no complete unanimity in the post apostolic Church on this topic—there never is on any theological topic. With that said, it is important to track the development of the tradition and practice in order to appreciate how we have arrived where we are today.

To deny that the Church believed in a supernatural reality occurring in the partaking of the body and blood of Christ at the Lord’s Table is a preposterous claim that misreads the intent of both Paul and John.

There are numerous theological ideas floating around in the Early Church, which we can witness in our canonical writings. Paul and John seemingly agree concerning Jesus as the paschal sacrifice. John and Matthew agree on the wording of the Words of Institution. Mark and John agree that the Feeding of the 5,000 is a foretaste of the Last Supper and—by extension—the Eucharist, and these two Evangelists agree with Paul that there is a connection with the manna from heaven in the Wilderness. Multiple images are all at play when discussing early Eucharistic practices, and we must let each author speak for himself before analyzing how this vein of tradition evolved into an understanding that Jesus is literally present in the bread and the wine.

From this study, we can conclude, at least minimally, that the earliest Christians did not believe that this was just a meal of bread and wine. Paul explicitly relates them to ingesting spiritual food; he goes so far as to say consuming the Eucharist improperly can lead to sickness and death. Mere bread and wine lack the qualities to produce such a result. Paul also appeals to a tradition—all the documents make this statement—that Jesus said “this is my body.” It is not a metaphorical statement for Paul.

As such, by the time we arrive at John’s Gospel, the theological discussion surrounding this spiritual sustenance has evolved greatly. John has explicitly stated his theological view that Jesus intended a supernatural consumption of his flesh and blood for the reception of spiritual sustenance. Again, it is far too much to assume a Thomist perspective of Transubstantiation here in the first and second centuries, but to deny that Paul, the Gospels, and the Early Church intended a spiritual and real participation with Christ in the Eucharist is absurd, and it is an intentional misreading of the documents.

If you have enjoyed this analysis of John 6, et al., and you wish to read more about the New Testament, would you kindly subscribe?

See also Origen, “We may venture to say that the Gospel according to John is the first fruits of the Gospels. For it is not possible to conceive of any other Gospel as speaking so clearly of the divinity of the Word who was in the beginning with God, and who became flesh and dwelt among us.” (Commentary on the Gospel of John 1.6)

For instance, in John 3 with Nicodemus, the dialogue only makes sense in Greek. The ambiguity and confusion could not have arisen in Aramaic. This discourse is likely a fabrication by John to discuss the sacramental and theological significance of baptism. Is it possible two Jews could have had a conversation in Greek like this? Yes, but it would be far more natural and probable that they would have been speaking Aramaic.

Regardless of how one reads John—as I have proposed or a more traditional approach—one must accept that what is recorded cannot be verbatim what Jesus spoke in every instance. There is creativity and authorial license when recording speeches, as I have written elsewhere. A good example from antiquity on speech writing can be found in Thucydides,

Therefore the speeches are given in the language in which, as it seemed to me, the several speakers would express, on the subjects under consideration, the sentiments most befitting the occasion, though at the same time I have adhered as closely as possible to the general sense of what was actually said (1.22.1 LCL).

Remember, there were no recording devices in antiquity. Speeches were approximations at best unless someone was writing down what was being said. If we wish to go a more traditional route and assume everything recorded is from Jesus’s mouth, at minimum one must concede that this is generally what was said rather than exact. This is especially the case since John is such a later text than the Synoptics.

Lastly, authors do not write just to present raw data with no purpose. John had intent. John had a reason for writing his Gospel. Each pericope and speech was placed in the text to make a theological, christological, etc. point As such, this is what I am truly attempting to emphasize. We must read the passages with the purpose of understanding what John wanted the reader to comprehend concerning Jesus, the Church, (here) the Sacraments, etc.

That is not to say that the Synoptics were unified in what they wanted to present. They had their own reasons for writing, but John’s is rather distinct in comparison.

I choose to use the word “Eucharist” as an all-encompassing term in this article. The Early Church used various terms to describe this rite, but I am going to use this for convenience.

This may be pre-Pauline/Christian tradition. See R. Collins, First Corinthians (Liturgical, 1999), 364.

For baptism in Paul, see R. Schnackenburg, Baptism in the Thought of St Paul (Engl. trans., Blackwell, 1964).

P. Perkins, First Corinthians (Baker, 2012), 123 remarks, “By speaking of spiritual food and spiritual drink Paul equates the wilderness sustenance with the bread and wine of the Christian meal.”

Cp. J. Fitzmyer, First Corinthians (Yale, 2008), 381. H. Conzelmann, 1 Corinthians (Fortress, 1975), 166 held a sacramental reading here.

For an extended discussion of the Cup of Blessing and the paschal elements, see Thiselton, First, 756ff.

A. Thiselton, The First Epistle to the Corinthians (Eerdmans, 2000), 726 holds,

As we should expect in Paul’s use of spiritual, the adjective does not mean immaterial, but that which is provided by the Spirit of God (cf. 9:11; 12:1; 15:44, 46), with all the “hallmarks” of what is regarded as a miraculous provision. In spite of numerous claims that spiritual food and drink become synonyms for the eucharistic elements in the subapostolic period (e.g., Didache 10:3, πνευματικὴν τροφὴν καὶ πότον), such a meaning cannot be read back into Paul

I am not arguing for “eucharistic elements” here in Paul. Rather, I believe that Paul holds a spiritual, miraculous event happening in the Eucharist. There is something unique occurring compared to normal feasting. The usage of “bless” and “break” have clear associations with a Last Supper tradition, which we will explore later, and this shows that there is a ritualistic understanding here.